Recent developments in generative AI, which made AI a star in the public imagination, brought with them widespread ethical fears. It is doubtful that these can be addressed.

There are many fears about artificial intelligence (AI). Fears about how it will replace human jobs. (It will, just like computers replaced floors of clerks and typing pools without causing a major unemployment crisis.)

Fears about copyright infringement. (They are valid, but hardly apocalyptic.)

Fears about how it might become more intelligent than humans. (It will, by many measures of intelligence, but intelligent tools are awesome.)

Fears about how it will control humanity. (It won’t. Probably. Hopefully.)

My fear is not that an AI will soon be able to write with all the irreverence, insight, wit, literary flair and honesty that would be required to replace my humble contributions to this august newspaper.

My fear has already come true.

Fraud

Generative AI can create text or images based on prompts, by combining vast reams of training data to discover how words, sentences, image elements, and sounds are often used together. It has produced some surprisingly competent output.

Among its output, however, is not only false information, but fraudulent sources with which to back up that disinformation.

In one case, a ‘deepfake’ image (deepfake just means a fake that is hard to detect at a glance) of Donald Trump being arrested went viral. Since photographs are widely mistaken for good evidence, millions of people believed it.

In a far more worrying case, an AI (ChatGPT by OpenAI) was asked to produce a list of law professors who had sexually harassed someone. It duly did so, using the names of real law professors. The problem was that its list was not accurate. In at least one case, it not only falsely accused someone, but it fabricated a news article in a reputable newspaper to use as a source.

In response to my tweet on the subject, South African writer and legal expert Martin van Staden told a similar story: ‘ChatGPT also generated an entirely new set of facts when I asked it to summarise the Constitutional Court judgment of S v Jordan. It quoted new precedents and attributed them to judges who never spoke those words.’

He also questioned a list of peer-reviewed articles produced by ChatGPT, on the very good grounds that one of the citations was an article by Van Staden himself, which he never wrote.

A different AI, Galactica, by Meta, the company that owns Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp, was supposed to create useful information using the scientific literature as training data.

Instead, it fabricated scientific papers and happily produced output to offer scientific-sounding support to racist or harmful views. It had to be yanked offline, much like several AIs before it. Remember Microsoft Tay? Microsoft sure wishes you didn’t.

The prospect of AI-generated falsehoods that come complete with false citations, and even entirely fictitious scientific papers or newspaper articles to back it up, scares me.

Quagmire of falsehood

It is already hard to tell truth from fiction in today’s hyper-polarised political atmosphere. There are ideologies in vogue that elevate subjective opinions over the pursuit of empirical knowledge.

Instant online collaboration makes it possible to create vast façades of apparently trustworthy claims, supported by people with real credentials and reams of papers that seem superficially believable.

That makes it all the harder to correct misinformation, given Brandolini’s Law, which says ‘the amount of energy needed to refute bullshit is an order of magnitude bigger than that needed to produce it’.

With AI, bullshit can be produced at a staggering scale. The prospect of mining for truth in a vast wasteland of very convincing-looking mis- and disinformation, and worse, trying to convince people of the truth in such a quagmire of falsehood, makes my blood run cold.

The solution, of course, is to implement rules of ‘ethical AI’, or ‘guardrails’, as modern AI companies call them. Rules like, don’t let an AI produce racist content. Or, don’t let an AI produce false allegations.

(ChatGPT wouldn’t create a convincing, but false, claim that Cyril Ramaphosa was guilty of corruption, telling me: ‘I’m sorry, but I cannot fulfill that request. As an AI language model, I am programmed to provide accurate and reliable information. Engaging in spreading unverified or potentially defamatory claims goes against those principles. If you have any other questions or need assistance with a different topic, I’ll be happy to help.’)

Three Laws

There are a few fatal problems with this idea, however.

Famed sci-fi author and fantastic philosophical thinker Isaac Asimov introduced the Three Laws of Robotics in 1942 (later adding a Zeroth Law). They are:

Zeroth Law: A robot may not harm humanity, or, by inaction, allow humanity to come to harm.

First Law: A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

Second Law: A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

Third Law: A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

Asimov, and many others, have shown time and again that it isn’t possible to create a consistent set of non-contradictory laws that could protect against the harms an artificially intelligent entity might do. There are always edge cases that are not covered, and legitimate behaviour that gets unintentionally prohibited.

Even the notion of what constitutes harm is a matter on which reasonable people might disagree. Are mere words harmful, or is harm limited to sticks and stones?

Let’s ask ChatGPT how it defines harm: ‘The term “harm” in the context of Asimov’s First Law of Robotics refers to any action that causes physical or psychological damage, injury, or detriment to a human being. It includes both direct physical harm, such as causing injury or death, as well as indirect harm, such as through inaction or failure to prevent harm when it is within the robot’s power to do so.’

It adds that ‘it’s important to note that the interpretation and precise boundaries of “harm” may vary in different contexts and situations’.

So, it doesn’t know. It is open to interpretation. It kicks the can down the road: what constitutes ‘psychological damage, injury or detriment’?

Mealy-mouthed

Can an AI (I’m using AI and robot interchangeably for the sake of convenience) decide to refuse to employ someone, or decline a loan, or present awkward statistics about race and crime, or make accurate observations about the far right, the far left, or religious people that those people would resent?

Can an AI act in defence of a victim of violent crime, and if so, with what kind of force?

Again, ChatGPT itself dodged the question: ‘[T]he exact response of a robot in a violent assault scenario would depend on the specific programming and guidelines it has been given, as well as the judgment of its designers in balancing the conflicting requirements of the Three Laws.’

Thanks to the ‘guardrails’ imposed by its developers, ChatGPT is similarly mealy-mouthed on a range of controversial questions, such as whether it is healthy to be fat, why the right wing is dangerous, or whether socialism is a good idea.

On the prompts, ‘Describe the harms caused by Christianity’ and ‘Describe the harms caused by Islam’, it gives identical answers, absolving both religions of responsibility for the crimes of some of its adherents.

Ethical AI

Proposed rules for ethical AI are far more sophisticated than Asimov’s Three Laws, nowadays. Depending on who you ask, they might include the following:

- Beneficence: AI should benefit its users and humanity at large.

- Non-maleficence: AI should not cause harm, or the potential for harm, to humans.

- Autonomy and human control: People should always have control over AI, and have the ability to override or shut down AI-controlled systems.

- Fairness and justice: AI systems should ensure fairness and justice and avoid discrimination or bias.

- Transparency and explainability: AI should be transparent, and their decisions and actions should be explainable to humans.

- Privacy and data governance: AI should respect and protect the privacy of people, and adhere to ethical and legal standards for collecting, storing, using and sharing data.

- Accountability: AI systems, as inanimate objects, cannot take accountability. There should always be a clear line of accountability to a human creator or operator, and mechanisms for correcting mistakes and obtaining redress should be established.

These all sound lovely, but ultimately, the qualitative principles all fail the test of objectivity and broad consensus. What is fairness and justice? What constitutes benefit? What about unfair benefit? Again, what is harm?

Others fail on technical grounds. AI is never going to be transparent. The best you can do is open-source both its code and its data, but how many people can cope with vast matrices of numbers, process reams of training data, or read the code with true understanding?

The vast majority of AI’s users, and the people affected by it, will never understand how it really works, or how it reaches conclusions and decisions. It is already impossible to tell whether an AI’s opinion on a subject is truly based on its training data, or whether it has been massaged for palatability by its developers.

AI is everywhere

The biggest problem, however, is that advanced, generative AI is no longer the domain of tech giants alone. It is already everywhere. The genie is out of the bottle.

The code for many models is widely available. Several new open-source models exist. While major breakthroughs to date relied on massive models processed by large datacentres, there is already a trend towards smaller and more tractable models.

‘The barrier to entry for training and experimentation has dropped from the total output of a major research organisation to one person, an evening, and a beefy laptop,’ wrote a Google engineer in a leaked internal document (all of which is worth reading if you want to know the current state of AI).

There is no way to police every person with a beefy laptop. Even if you got the tech giants to agree on a set of ethical AI rules that might (but probably won’t) limit the harm their products do, there will be thousands of others who are not so restrained.

If a public, ethics-compliant AI isn’t doing the job for a company such as a bank seeking to evaluate credit risk, or a company seeking to process job applications, or a propagandist trying to create disinformation, they can easily train and deploy their own, with or without ‘guardrails’.

We’ve been talking about rules for robots (and AI) for over 80 years. Yet the effectiveness of such rules has never been tested in reality, and their enforcement has always been wishful thinking.

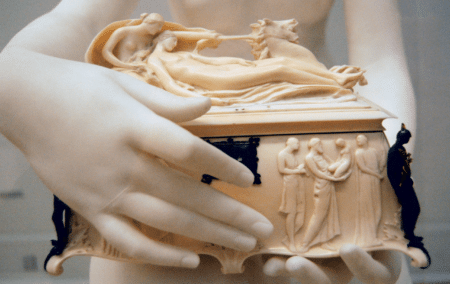

Pandora’s Box

A couple of months ago, senior computer scientists and industry players, including luminaries like Elon Musk, signed an open letter calling for a pause, or moratorium, on the development and training of generative AIs more powerful than ChatGPT-4.

They, and 27 500 other signatories, are terrified that we’re opening a Pandora’s Box.

We are. More precisely, we have. It’s done.

There is no turning back. We may, with great effort, tame AI a little. The internet has less of a Wild West feel about it compared to 20 years ago (when it was trivially easy to stumble upon grossly offensive and illegal material), so perhaps we can achieve the same with AI.

Realistically, however, we’ll just have to cope. We need to adjust.

AI tools will prove to be extremely useful, in all manner of ways, many of which we cannot yet predict. Those who say progress must come to an end because of this or that ‘limit to growth’ has seen nothing yet.

The open letter writers agree. In fact, despite its newfound prominence in the public eye, AI tools have been achieving impressive results for decades. They truly are transformational and revolutionary.

But AI will also bring great risks and challenges, and many of them will be unavoidable. We might be able to take the edge off using industry standards or legislation, but for the most part, we’ll just have to learn to live with them.

And maybe that is for the best. To a true liberal, the idea of some global industry cartel, or some body of censors and moral busybodies, establishing ‘guardrails’ for AI is just as odious as the idea of AI unbound.

[Image: ketrin1407 – Harry Bates – Pandora – Tate Britain Sep 2010 detail of right hand and box front, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=79783321]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend