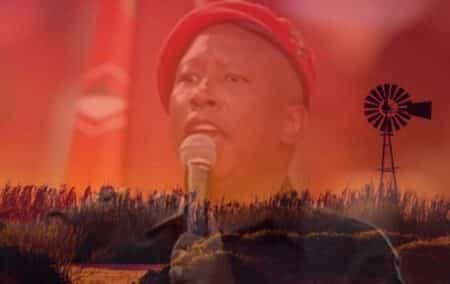

In the wake of the controversy occasioned by Julius Malema leading his supporters in a chant of ‘Kill the Boer’ and ‘Shoot to Kill’, South African-born tech magnate Elon Musk called out South Africa’s President.

In a post on the platform X (formerly Twitter), he wrote: ‘They are openly pushing for genocide of white people in South Africa. @CyrilRamaphosa, why do you say nothing?’

While Malema’s words were a major point of contention in South Africa, they attracted attention in the United States too. Two important outlets, The Washington Post and The New York Times, carried substantial pieces, directed less at Malema and his place in South Africa’s politics than at Elon Musk and his supposed endorsement of the ‘white genocide’ myth. For the record, Musk did not do so, although he did accuse Malema of calling for genocide – on the use of the words, that is not an entirely unreasonable contention.

They also argued that concerns about violence against farmers are overblown, implying that they are fuelled by racist sentiments, while providing some quasi-justificatory contextualisation for Malema’s behaviour.

The Institute feels that discussion about South Africa, whether domestically or abroad, must be informed by facts. The pieces in question in our view fell very short in this regard.

In the interests of accuracy, we attempted to correct the mischaracterisations made in these articles. Neither newspaper has published our response. We reproduce the two letters below.

The Washington Post

Although confined to fringe elements in South Africa, the trope of ‘white genocide’ (‘Elon Musk raises the specter of “white genocide”’, 1 August) seems to exercise an influence on particular foreign observers for whom the country functions as a stage for their own morbid fixations.

This applies to voices on both ends of the spectrum: for some as symbolic of the demise of Western civilisation, for others as a caricature to stigmatise concerns about the murder of farmers.

The reality is that violence against farmers and rural insecurity in general is a serious problem, and is by no means one confined to white farmers. Whether farmers face an elevated risk depends largely on how the data is processed and interpreted.

However, for a country with South Africa’s factious politics and scale of socio-economic problems (including a murder rate of some 42 per 100 000; the US rate is around 7 – World Bank data for 2021), incendiary rhetoric and the debased politics it signifies augurs badly for the country’s future as a constitutional democracy.

In this sense, Elon Musk may be right: why would the country’s president avoid taking a position on this?

Terence Corrigan

Institute of Race Relations, Johannesburg

The New York Times

Your correspondent John Eligon (‘”Kill the Boer” Song Fuels Backlash in South Africa and U.S.’, 2 August) is incorrect in claiming that South Africa’s Economic Freedom Fighters ‘[advocate] taking white-owned land to give to Black South Africans.’

The EFF locates its posture within ‘the Marxist-Leninist and Fanonian schools of thought.’ Its first ‘non-negotiable cardinal pillar’ is for the ‘expropriation of South Africa’s land without compensation for equal redistribution in use.’

In other words, while it promises to dispossess white people, it has no intention of transferring anything at all. It seeks state ownership (custodianship in the South African lexicon) with land then being leased at the state’s discretion to individuals, households and businesses. Its objective is to abolish private property in land entirely.

In this, it is actually not too far removed from the governing African National Congress. Such a mass custodial taking has been publicly endorsed by state and party officials, along the lines of what has already occurred with water and mineral rights. While this has not been actioned, it is notable that official land redistribution policy (acquiring and passing on land on the basis of need) rejects private freehold for beneficiaries, making them tenants of the state. And there is a long-standing ambiguity about extending proper ownership of both urban and rural properties to the black people occupying them – a shameful holdover from the apartheid period.

This has exposed millions of people to the effective control of an often venal and incompetent state.

The notion that the EFF (or indeed the incumbent government) seeks racial redistribution from one group to another is widespread, and perhaps a beguiling one. In ignoring the ideological drivers and policy assumptions, it is mistaken, and repeating it contributes to misunderstanding South Africa’s political dynamics.

Terence Corrigan

Institute of Race Relations, Johannesburg

[Image: Dimitris Vetsikas from Pixabay, superimposed on a screenshot]

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend