This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

15th September 994 – The Battle of the Orontes, in which forces of the Fatimid Caliphate win a victory over the Eastern Romans and their allies

The Orontes River in Hama, Syria [Vyacheslav Argenberg / http://www.vascoplanet.com/, CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=108922985]

One of the great conflicts of history was the epic clash between the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine Empire) and the various Arab Islamic empires of the Middle East.

Beginning in 629, with the rise of the first Islamic empire, the Rashidun Caliphate, the Romans lost many of their most valuable territories in the Levant, Egypt and North Africa.

At one point the Arab armies even struck deep into Anatolia and laid siege to the mighty capital of the Eastern Romans, Constantinople, in 674.

Coin of the Rashidun Caliphate (Byzantine imitation circa 647–670), with Byzantine figure (Constans II holding the Crusader sceptre and globe) [Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=71064631]

The Romans would throw back the attackers and endure, battling for control over Anatolia.

The war between the Arabs and Romans would settle into a familiar pattern.

Every spring, thousands of men from across the Islamic world would answer the call of Jihad, or struggle, a call for holy war against the infidel Romans. Large Arab armies would strike into Anatolia, to raid and plunder the land and take slaves, livestock and loot back to the Caliphate.

The Romans would keep a watch on the mountain passes leading into Anatolia, and when they saw the Arabs coming, would alert the capital by messenger on horseback or sometimes by lighting giant fires in a huge network which could send the warning of an attack hundreds of kilometres in the space of a few hours.

Roman civilians would drive their livestock and take their valuables into a network of small forts situated on hills across Anatolia, where small garrisons would hope to hold out.

When the Arabs had finished their raid, largely unopposed, they would turn for home, but now weighed down with loot. At this point, Roman troops sent from the capital would strike, often ambushing the Arabs in passes or valleys. Attacking the Arabs head on was risky, and trying to stop the raiders could see the Roman forces crushed and leave their lands even more vulnerable than before, but by waiting to catch the Arabs on their way home they hoped to catch them at their weakest and deny them the loot they sought.

Sometimes the Arabs would escape home, sometimes the Romans would slaughter the raiders in ambush, sometimes they would simply recapture the loot with the Arab troops mostly managing to get away.

This pattern of conflict continued almost every year from the late 600s to the late 800s, almost two centuries of nearly constant war.

Syrian tile panel (c. 1600) with the names of the four Rashidun Caliphs [Qubbat3924, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=83881238]

While the Roman Empire would endure, the Arab Islamic Caliphate would go through many convulsions. The original Rashidun caliphs would be replaced by the Umayyads, who would in turn be overthrown by the Abbasids. Over time the Caliphate lost more and more territory, and the Islamic world splintered. Increasingly the Arab armies came to be dominated by Turkic mercenaries who would slowly take power from their Arab masters.

In the 930s, during the reign of the Emperor Romanos I Lekapenos, an Armenian Roman general called John Kourkouas would lead a series of successful campaigns that began to extend Roman control beyond Anatolia and back into Syria for the first time since the 600s. The balance of power had now swung back to the Romans, who now became the aggressors.

The most powerful Islamic power opposing the Roman advance into Syria was the new Fatimid Caliphate, a Shiite caliphate based in Egypt. All through the 900s and first half of the 1000s the Romans and Fatimids would battle for control of Syria.

In the late 900s, after years of battling the Romans, the Muslim rulers from the Hamdanid dynasty based in the city of Aleppo would agree to become vassals of the Roman emperor in 969.

The growing power of the Romans in Syria saw more and more clashes with the Fatimids, who ruled the Levantine coast. In 994, the Fatimids sent a Turkish general called Manjutakin to attack the Romans in Syria. The Roman governor of Antioch, Michael Bourtzes, gathered an army of Roman troops and allied Hamdanid forces to beat back this attack.

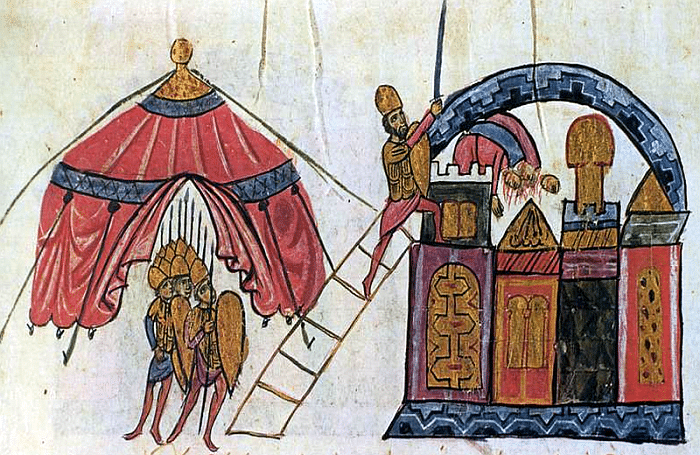

The capture of Antioch on 28 October 969 by the Byzantine forces under Michael Bourtzes (shown stepping onto the wall), from the chronicle of John Skylitzes

On 15 September 994, the Roman and Fatimid armies engaged in battle at the Orontes River. The Fatimids pinned down the Roman forces with their tough Turkish troops and then attacked the flanks where the allied Arab troops were supporting the Romans. They broke through and the Roman army panicked and ran, suffering at least 5 000 dead.

After this battle, the Fatimids took control of Syria, and expelled the Hamdanid rulers. However, Roman Emperor Basil II soon led a new army into Syria. Caught unawares, the Fatimids fled back to their base in Damascus, without giving battle, thus allowing the Romans to recapture northern Syria.

The Romans would soon have to turn their attention to the growing threat of the Turkish Seljuk Empire. In 1071 the Romans would be defeated at the Battle of Manzikert and would never hold power over all of Anatolia again.

The Entry of the Crusaders into Constantinople, by Eugène Delacroix, 1840

Despite occasional revivals, a brutal sack of Constantinople in 1204 by a Crusader army would cripple the empire – although it would hold on until 1453, when the Ottoman Empire finally captured Constantinople.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend