This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

31st October 2011 – The global population of humans reaches seven billion. This day is now recognised by the United Nations as the Day of Seven Billion

Image: Gerd Altmann from Pixabay

For most of history and pre-history, the global human population has been very difficult to estimate. Before organised modern states and modern data analysis, most pre-modern estimates of global population were little more than well thought out guess work.

Making matters worse, even once we begin to get written historical sources and estimates of things like army sizes, ancient authors are notorious for massively inflating numbers to make their writing more exciting.

Before the invention of agriculture around the year 10 000 BC all human populations on earth were small bands of hunter-gatherers, rarely numbering more than around 100 people per group. Estimates of the global population in this time range from 1 million people to 15 million globally.

The invention of agriculture would revolutionise human society, and populations, now with stable food supplies for the first time, would explode.

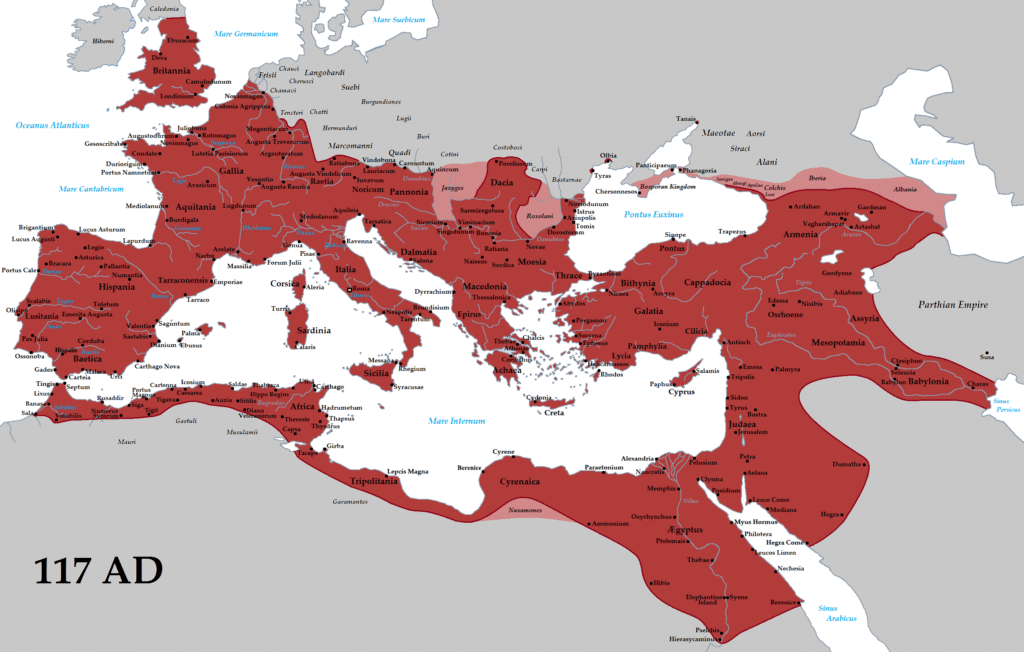

By the height of the Roman Empire in Europe and the Han Dynasty in China around the year 1 AD, estimates for the global population place it at around 232 million.

The Roman Empire (red) and its clients (pink) in 117 AD during the reign of emperor Trajan [Tataryn, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=19625326]

The things holding back population growth in the pre-modern period were, relative to modern agriculture, low levels of food production, periodic mass outbreaks of disease and high infant mortality. Around half of all children born would die before the age of five until relatively recently.

Disease outbreaks could be incredibly devastating, as the example of the Plague of Justinian, between 541 and 549 AD shows us. This plague outbreak, likely the first major outbreak of Bubonic plague in European history, killed between a fifth and a half of Europe’s population.

Saint Sebastian pleads with Jesus for the life of a gravedigger afflicted by plague during the Plague of Justinian (Josse Lieferinxe, c. 1497–1499)

Between the 500s and the 1300s, global populations would rise and fall periodically in response to war, disease, and climate change.

Global populations would peak in the 1200s before crashing again due to the Mongol conquests of much of Eurasia. Between 1206 and 1348, the marauding Mongol armies would kill somewhere between 40 to 75 million people.

Expansion of the Mongol Empire 1206–1294 superimposed on a modern political map of Eurasia

The new Mongol Empire also established new trade routes between Asia and Europe and so would transmit a second major plague outbreak from Asia to Europe in the mid-1300s.

In the Americas and Africa, populations were generally lower and concentrated in smaller pockets of developed areas such as Mexico, the Andes Mountains and the Mississippi valley. In Africa, the population centres were West Africa and the Ethiopian highlands.

Populations would remain at a low ebb until the 1500s.

Good climate, growing trade networks and improving technology would see populations begin to creep up across the world starting in the 1500s. The Americas however would suffer a population calamity as new diseases brought accidently by Europeans to the continent would kill millions. Pre-contact Americas had a population of somewhere between 10 million and 100 million people (estimates are difficult to agree on) and this would fall by 20%-90% over the 1500s and 1600s.

Sixteenth-century Aztec drawings of victims of smallpox (above) and measles (below)

The global population hit around 500 million in the year 1600 and, almost every year from this point onwards, continue to grow.

In the mid-1600s the British and Dutch developed new revolutionary farming techniques and began to farm new crops imported from the Americas. This would cause a huge boost in food production and these new methods would quickly spread across the world, rapidly expanding the global food supply.

In 1770 the world’s population had boomed to 770 million.

Around this time the Industrial Revolution began in Britain and once again this greatly improved material conditions. The rapid expansion of cities brought on by the Industrial Revolution led to the development of new forms of urban planning and sanitation, which for the first time turned cities from places where constant immigration was needed to maintain the population into places where the population grew on their own.

Over London–by Rail from London: A Pilgrimage (1872) by Gustave Doré

In 1804, the world’s population hit 1 billion for the first time.

More people meant more productivity and innovation – in contrast to before the Industrial Revolution when land availability had significantly limited the productivity of populations – new farming methods, and factories, meant that despite the global population exploding there was greater and greater material abundance.

By 1927 the world’s population had reached 2 billion.

In 1930 about half the global population lived in Asia, 500 million in Europe, and Africa and North America a distant third and fourth place with 170 million people each.

Despite world wars and the occasional pandemic, the global population reached 3 billion in 1960 and 4 billion in 1974. This rapid growth sparked fears in some intellectual circles that population growth would cripple humanity by the year 2000 as there would simply be too many people to feed.

This belief led to massive sterilisation campaigns in parts of the world, particularly India, as well as the notorious ‘one child policy’ in China. Movies like Soylent Green would popularise these fears, leading to their wide acceptance.

However, these fears were completely unfounded, for two reasons.

First, the rate of innovation and development vastly outpaced population growth, leading to more material abundance not less. Second, beginning in the 1970s the global population growth in percentage terms began to slow, as wealth, education, social security systems, changing cultural practices and more available contraception saw birth rates begin to plummet globally.

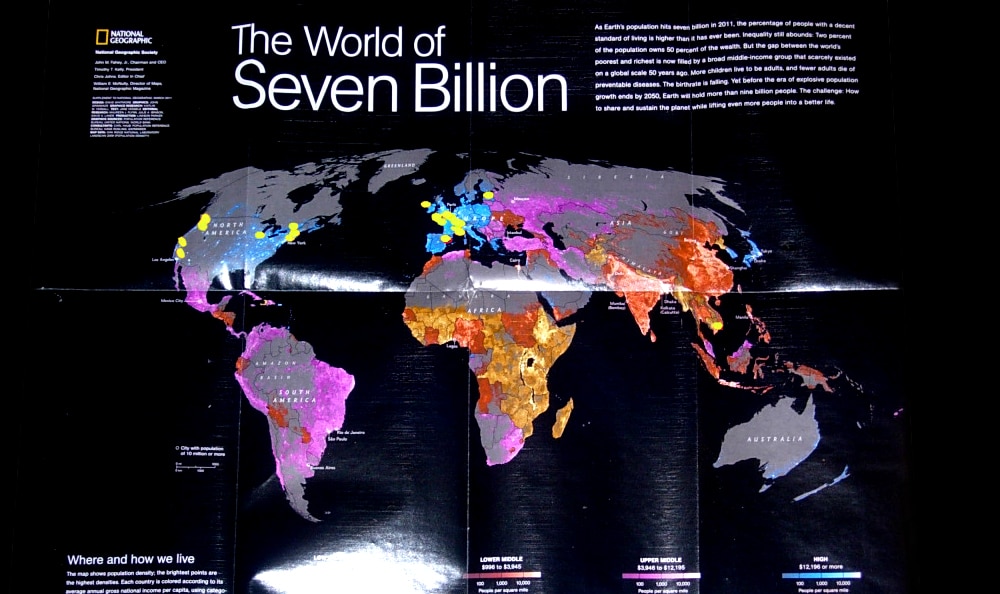

The 5 billion-people mark was reached in 1987, 6 billion in 1999 and – according to some estimates – on 31 October 2011 – the world reached 7 billion people. This date is recognised by the United Nations as the Day of Seven Billion.

[https://www.flickr.com/photos/andresmusta/5492899843/in/photostream/]

In 2022 global populations totalled 8 billion, but all straight-line estimates suggest that we are heading for a stabilization of population between 10 and 12 billion sometime before 2100.This marks the first sustained slowdown in population growth since the 1600s.

It is also a slowdown felt all over the world. While poorer countries, particularly in Africa, now have much higher birth rates than those in Europe and Asia, they too are seeing major drops in their birth rates.

For the first time in many centuries, human beings will have to think about their societies as places where there might be many fewer people tomorrow than there are today.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend