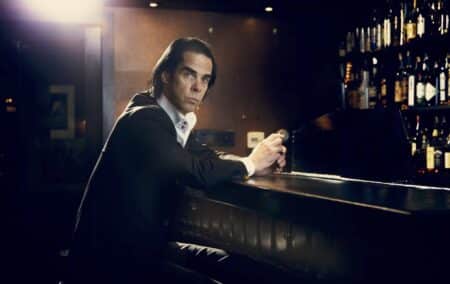

Generative artificial intelligence is a ‘boundless machine of artistic demoralisation’, says singer Nick Cave.

Australian singer, writer and actor Nick Cave really doesn’t like generative artificial intelligence in general, and OpenAI’s ChatGPT in particular.

That is, of course, his prerogative, but in a recent public letter directed at a pair of would-be song-writers, he makes a fervent and histrionic appeal to fight this ‘existential evil’: ‘we should fight it tooth and nail, for we are fighting for the very soul of the world’.

I will quote his letter below, but you can read it on his website, The Red Hand Files, or you can have Stephen Fry read it to you in the Albert Hall.

Cave’s letter is addressed to two people, Leon and Charlie.

Leon, who hails from Los Angeles, asked the following: ‘I work in the music industry and there is a lot of excitement around ChatGPT. I was talking to a songwriter in a band that was using ChatGPT to write his lyrics, because it was so much “faster and easier.” I couldn’t really argue against that. I know you’ve talked about ChatGPT before, but what’s wrong with making things faster and easier?’

Charlie, from Leeds in the UK, just wanted to tap Cave’s wisdom: ‘Any advice to a young songwriter just starting out?’

Grandiose metaphor

Cave uses a rather grandiose metaphor, which draws an analogy between artists and their work, and God creating the world.

Writes Cave:

‘In the story of the creation, God makes the world, and everything in it, in six days. On the seventh day he rests. The day of rest is significant because it suggests that the creation required a certain effort on God’s part, that some form of artistic struggle had taken place. This struggle is the validating impulse that gives God’s world its intrinsic meaning. The world becomes more than just an object full of other objects, rather it is imbued with the vital spirit, the pneuma, of its creator.’

Cave has an apparently rather conflicted relationship with God. He doesn’t like organised religion, doesn’t believe in a personal God, and doesn’t like atheism either. He has said that every love song is a song for God, and that ‘there is some divine element going on within my songs’.

Grand. Good music flows out of his tortured mind, whether or not it makes sense to us, or even to himself.

Only 31% of the world’s people believe in the Christian God, and, counting Muslims and Jews, only 55% accept the Abrahamic God. The rest either follow non-Abrahamic religions, or are not religious at all, and therefore would not agree that the meaning of their own existence derives exclusively from the spirit or creative effort of Nick Cave’s conception of God.

And those who would agree might take exception to Cave’s pretensions of grandeur when he compares his own artistic struggles with those of God.

However, if Stephen Fry, who is an outspoken atheist, could hide his aversion while reading this religious sop, then so will I.

Let’s just acknowledge, then, that by way of analogy, Cave meant to imply that the value of a work of art or music derives from the ‘artistic struggle’ of the artist.

Universal unconsciousness

Cave continues:

‘ChatGPT rejects any notions of creative struggle, that our endeavours animate and nurture our lives giving them depth and meaning. It rejects that there is a collective, essential and unconscious human spirit underpinning our existence, connecting us all through our mutual striving.’

Again, he veers into the spiritual and the speculative, making claims about some sort of universal consciousness (or rather, unconsciousness) that many people would only very vaguely acknowledge, and many people – especially committed individualists – would disdain.

Cave clearly has a very exalted view of the significance of his art, believing that it somehow transcends the physical world.

‘ChatGPT is fast-tracking the commodification of the human spirit by mechanising the imagination. It renders our participation in the act of creation as valueless and unnecessary. That “songwriter” you were talking to, Leon, who is using ChatGPT to write “his” lyrics because it is “faster and easier,” is participating in this erosion of the world’s soul and the spirit of humanity itself and, to put it politely, should fucking desist if he wants to continue calling himself a songwriter.’

I entirely agree that if you let an AI – which is itself a rather grandiose term for a statistics-based plagiarism engine – write your songs, it would certainly be ‘faster and easier’, but you should also be ashamed of calling yourself a songwriter.

That such actions constitute ‘the erosion of the world’s soul and the spirit of humanity itself,’ however, is overwrought.

Anthropomorphising ChatGPT

‘ChatGPT’s intent is to eliminate the process of creation and its attendant challenges, viewing it as nothing more than a time-wasting inconvenience that stands in the way of the commodity itself. Why strive? it contends. Why bother with the artistic process and its accompanying trials? Why shouldn’t we make it “faster and easier?”’

Cave anthropomorphises ChatGPT, treating it as an intelligent agent to which purpose and motives can be attributed.

It isn’t, of course. It is a tool. It is technology that can be used in any of a myriad ways. It is usually used to automate routine tasks, and is, frankly, quite poor at more demanding work.

As Cave said himself about a song that ChatGPT produced ‘in the style of Nick Cave’: ‘This song sucks.’ (It did suck, and was rotten with clichés.)

If ChatGPT has any ‘intent’, it is to reduce time wasted on routine tasks. It is, by its very nature, not capable of original thought or art. Its output is, by definition, derivative.

‘It was good’

‘When the God of the Bible looked upon what He had created, He did so with a sense of accomplishment and saw that “it was good”. “It was good” because it required something of His own self, and His struggle imbued creation with a moral imperative, in short, love. Charlie, even though the creative act requires considerable effort, in the end you will be contributing to the vast network of love that supports human existence. There are all sorts of temptations in this world that will eat away at your creative spirit, but none more fiendish than that boundless machine of artistic demoralisation, ChatGPT.’

I’m not sure why Cave believes that any artist ought to be able to look upon their work and declare that ‘it was good’.

I’m sure all artists would like to, but objectively, that is clearly not true. A lot, and perhaps the vast majority, of ‘art’ is unadulterated rubbish.

I know a guy, perhaps five or ten years older than Cave, who indefatigably pours ‘something of his own self’ into his ‘art’. Yet he produces infantile drawings that might earn a nine-year-old a pass, but are embarrassingly bad as art.

Does his ‘struggle [imbue his] creation with a moral imperative, in short, love’? Well, sure, his wife claims to love them. But nobody else does.

It also confuses me why Cave views ChatGPT as a ‘boundless machine of artistic demoralisation’.

ChatGPT probably couldn’t have come up with that flowery phrase. Is Cave really so insecure about his own creative abilities that he feels intimidated by an advanced version of Microsoft’s Clippy?

Commodification

‘As humans, we so often feel helpless in our own smallness, yet still we find the resilience to do and make beautiful things, and this is where the meaning of life resides. Nature reminds us of this constantly. The world is often cast as a purely malignant place, but still the joy of creation exerts itself, and as the sun rises upon the struggle of the day, the Great Crested Grebe dances upon the water. It is our striving that becomes the very essence of meaning. This impulse – the creative dance – that is now being so cynically undermined, must be defended at all costs, and just as we would fight any existential evil, we should fight it tooth and nail, for we are fighting for the very soul of the world. … Love, Nick.’

I’m not convinced that the impulse to make beautiful things is being undermined at all.

Cave’s fear of this new ‘commodification’ of ‘creation’ is nothing new.

Many an essay has been written by our elders about how mass production in factories, and later, plastic injection moulding, or poster printing, represented an awful commodification of the objects with which we surround ourselves.

It may appear that the world no longer values beautiful oak furniture, and lovely hardwood toys, and glorious leather-bound books. But that’s not true.

The truth is that those things were really only ever reserved for the rich, and still are. The ‘commodification’ of mass production has not cheapened bespoke production. It has merely made what once were unattainable luxuries commonplace even in the homes of the poor.

It is true that ChatGPT and similar generative AIs will churn out vast reams of commodified ‘content’, some of it intended for business purposes, but much of it for commercial entertainment.

The thing is, we’ve been churning out garbage without the help of AI forever. In every era in human history, we have produced reams of schlock aimed at the lowest common denominator.

Cheap and mindless

People make fortunes producing formulaic romance or detective novels as fast as they can type. Will the world really be worse off if those people employ ChatGPT to write their vacuous crap?

The cinemas (and lately our streaming services) have always been overrun with mindless action movies, trashy eye-candy, reality television and B-grade horror films that have no redeeming qualities whatsoever. Why shouldn’t they be produced more cheaply and more quickly by using AI technology?

We have circuses and WWE wrestling, for which no AI was necessary.

The rise of the internet has made everyone a publisher. There are 600 million blogs out there, producing 7 million posts per day, most of which are written for free.

The commercial media has certainly found it hard to compete with this massive explosion of ‘content’, most of which is rubbish, yet here I am, still writing for my supper.

If I can do it, I have full faith that Nick Cave can also keep his head above water by being creative, and that ChatGPT doesn’t really amount to an existential threat to his art or his ability to make a living.

Andy Warhol made an entire career out of lampooning and exploiting commercial, mass-produced junk.

Labour theory of art

Whose ‘spirit’ is Cave worried about here? The spirit of the creators of dreck, or the spirit of the incurious masses who enjoy that sort of thing?

Cave’s view of art – that it derives its value from the creative struggle the artist puts into it – reminds me a bit of Marx’s labour theory of value.

Not everything you produce has value, no matter how much time, materials or creative energy you invest in it. That you think it has value doesn’t give it value, either.

If you’re trying to sell me something, whether it’s cheap entertainment or high art, don’t tell me how much work or ‘creative struggle’ went into it. I couldn’t care less. All I care about is what the object is worth to me. What the art means to me.

I quite like Nick Cave’s music, not because it means something to him, but because it resonates with something in me.

Value and meaning are subjective. A work of art is not meaningful because the artists poured their heart and soul into it. It is meaningful only inasmuch as the viewer or listener appreciates it.

Good enough

For a lot of purposes, AI-generated art is good enough, just like computer-generated imagery (CGI) in films is good enough for many occasions.

For people who appreciate and seek out art and originality, it will never be a substitute.

Should Cave look down upon Leon, who wants ChatGPT to write his songs? Sure. I also look down on people who produce, or consume, vulgar content.

Is Leon harming anyone by using ChatGPT to write his lyrics? No, he risks harming only himself. He’ll be playing for an audience that doesn’t care, and be ignored by the audience that does. If that puts butter on his bread, good for him.

Millions of people like electronic music and other forms of repetitive and largely automated music that I (and presumably Cave) would sneer at.

Yet some people use computers and computer-generated music quite creatively, to do new things that were never possible before. That has merit, in my view.

Generative AI, likewise, is just a tool. Sure, you can produce trash with it, but producing trash is not a new ability. Some people will learn to use it to be more efficient, which is a win, and some people will learn to harness it to produce new kinds of art that simply weren’t possible before.

Pandora’s Box

There are plenty of reasons to fear the rise of generative AI. It should be feared as an engine of mis- and disinformation. It should be feared as an engine of plagiarism. However, as I’ve written before, it is a Pandora’s Box that cannot be closed.

It will be used, for better or for worse, whether Nick Cave likes it or not. It will expose a lot of what we thought was ‘creative’ and ‘skilled’ work to be merely routine tasks that can easily be automated.

In doing so, it will free up more of our time, just like the rise of agricultural machinery freed up time for people to engage in other forms of productive industry, and the rise of computers freed up time that we used to spend writing things long-hand in triplicate, or computing complex calculations by hand.

We might look back on the past with a naïve kind of nostalgia, but there is nothing mystical, spiritual or ennobling about writing in long-hand, reading by candlelight, or having to spend most of your day outdoors growing your own food.

New waves of technology have not dampened or undermined our creativity, and neither will generative AI do so. It will, perhaps, change where or how we direct our creative impulses. It will challenge us to raise the standards we set for ourselves. But it is not an ‘existential evil’ that we should ‘fight tooth and nail’.

People will continue to produce mindless junk, and artists will continue to produce transcendent art, and the world will go on turning.

The ‘soul of the world’ is not in peril.

[Photo: https://canchageneral.com/nick-cave-y-la-incertidumbre-del-pasado-y-futuro/]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend.