It might be crucial to note right away that there is a significant distinction between what is fact and what is uncomfortable to hear. What is uncomfortable to hear is anything that, if heard, might make someone feel uneasy or react negatively. Fact, on the other hand, refers to the reality of an occurrence rather than its interpretation.

As the author of this piece, I could not care less how anybody feels after reading it. What I hope this piece starts instead, is a thorough reflection by each reader of the facts surrounding our collective past and how complicated our history is. Regardless of our feelings, thorough reflection of facts should, of course, be guided by rational thinking rather than an emotional response.

Africa pre and during white-colonisation

These days, black consciousness and pan-Africanist activists, intellectuals and politicians like to present a romanticised image of black Africans prior to white colonisation, as though all black African tribes were living in perfect harmony and unity and that the great unity was only broken when white colonisers arrived and conquered black Africans. Factually speaking, this point of view is utterly untrue. Contrary to popular assumption, black Africans did not always get along before colonisation by white colonisers.

I still vividly remember a conversation with Ngaka Thotse, the younger brother of my paternal grandfather, back in 2018. He was telling a few men in the Thotse family about some of the fights that happened in the northern region of the province of Limpopo, South Africa, specifically in the area that is now known as the Sekhukhune district area, both before and during the rough colonisation days. As it happens, Ngaka Thotse is an African traditional seer who mainly went around delivering ancestral messages to mešate (kingdoms) across Southern Africa, during his healthiest days, and a keeper of a great deal of the Bapedi people’s oral history and custom. The fights he mentioned occurred in the Sekhukhune area and involved black African people from several tribes fighting under the command of various monarchs.

For me, learning from him about the origins of various tribal conflicts that took place in the Sekhukhune area was astounding. I remember Ngaka Thotse explaining how some battles would just break out when a stranger was spotted in a community. He told us how, for example, a man at a village’s river would run to his people and report that there was an invader in their area if he saw another man approaching and he did not recognise that man’s face – since villagers then all knew each other.

The King would then order the soldiers of the Kingdom to hunt down and murder the outsider. The King and his family would be taken into hiding into a cave if they ever suspected that the outsider had not arrived alone, which is why the majority of kingdoms were located atop mountains with caverns. After killing the outsider, the soldiers would search for any other companions he might have come with. And that is simply how some tribal wars amongst black African tribes started.

Historically, white colonists have of course used an irrational approach to handling matters amongst black African tribes to incite conflict and facilitate their easier conquest of these groups. For example, when white colonisers fought Sekhukhune I and the Bapedi Kingdom, they rallied many SiSwati armies to fight against him on the grounds that the victor would be crowned king of all the people in the region and would have complete control over the Sekhukhune area. This is how the Nchabeleng people, for example, and all the other ba bina Tau (the lion totem family) came up in the Sekhukhune region. There were no ba bina Tau among the original Bapedi people, who emerged from a confederation of small chiefdoms that had been founded at some point before the 17th century.

The fact is that if there had not previously been serious clashes among black African tribes, white colonisers would not have been able to ignite tribal conflicts amongst them. Ignoring this truth (which pan-African and black consciousness activists, intellectuals and politicians tend to do) is essentially a refusal to accept historical facts for what they are.

The unity of black Africans

There is no doubt that white colonisers did not intentionally want to unite black tribes in Africa. The unification resulted from the white colonisers’ and colonialists’ extreme brutality, which included dispossessing many black African people of their land and thus forcing removals from those lands, taking away many African people’s livestock, passing laws that were essentially antithetical to black African people’s customs, beliefs, and family unification, and more.

In South Africa, for example, it was the 1913 Natives Land Act, the 1948 advent of apartheid, and the harsh and violent policies of this regime that finally brought black South Africans together. Black Africans’ unity was about a group of people, who did not get along among themselves, realising they had to band together to battle a common enemy that they could not defeat if they all fought from various corners, due to the opponent’s more sophisticated weapons. There is no proof that black African tribes would be living in as much harmony as we do now if it were not for this shared adversary.

This is not to argue, of course, that praise should be given to the whites who colonised Africa and ruled over black African people. This is in no way an invitation for such praise. Actually, though, it is a call for us to consider history objectively. In a similar vein, we must consider how the Bapedi and the Zulu Kingdoms, for example, themselves came to be through colonisation and the subjection of other groups – specifically, black on black colonisation – rather than simply appearing out of nowhere. Which begs the question: if some people are truly repelled by colonisation, why do they constantly talk about white people against black people and not much about black people against black people? I get the impression that these people’s primary concern is the differing skin tones between white and black people, not so much the act of colonisation itself.

(I already discussed this subject in an article titled “The Race Question,” which was published on January 7, 2023 by The Daily Friend. I asked the same topic there as well: Why does the colonisation debate tend to focus mostly on white colonists rather than colonisation in its entirety).

Trade in Africa pre-colonisation

There is sufficient data to demonstrate that some black African tribes engaged in intercontinental trade as well as intra-African exchange of economic items with other African tribes prior to colonisation by the white coloniser. Numerous books and scholarly articles have been written about this. This clearly illustrates the fact that certain tribes saw the chance to trade, and did interact at this level rather than fighting each other. However, this was definitely the exception rather than the rule.

In closing

As previously mentioned by Helen Zille, the Chairperson of the Federal Council for the Democratic Alliance, despite strong criticism from various social groups and individuals, colonialism had some positive effects despite its many terrible aspects. These positive effects, in my opinion, go beyond things like great laws and public infrastructure to include the unity of black African tribes. Even while white colonisation and its brutality did not intentionally aim to bring black Africans together, it indirectly did, and the fact that black Africans no longer murder one another when crossing paths or fail to recognise one another’s faces is a great thing. White colonisers indirectly helped black Africans to arrive at this point.

To be completely candid, one opinion piece is insufficient to fully explore this matter. If resources permit, I would like to spend months researching this topic further and writing a more comprehensive book at some point in the future. It will include accounts of African trade, wars between African tribes, the long-standing resistance to white colonisation by numerous black African tribes that ultimately united these tribes, black-on-black colonisation cases in South Africa and other events.

Our past provides ample evidence for the opinions I am expressing here. These opinions must surely be expressed in order to dismantle the absurd one-street viewpoints that are taught in today’s numerous institutions, and promoted as the only true reality by intellectuals, activists and politicians for black and pan-African consciousness.

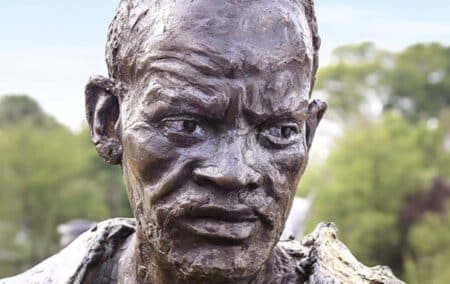

[Photo: Bronze of Sekhukhune I/Long March to Freedom]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend.