This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

December 6th 1917 – Finland declares independence from the Russian Empire

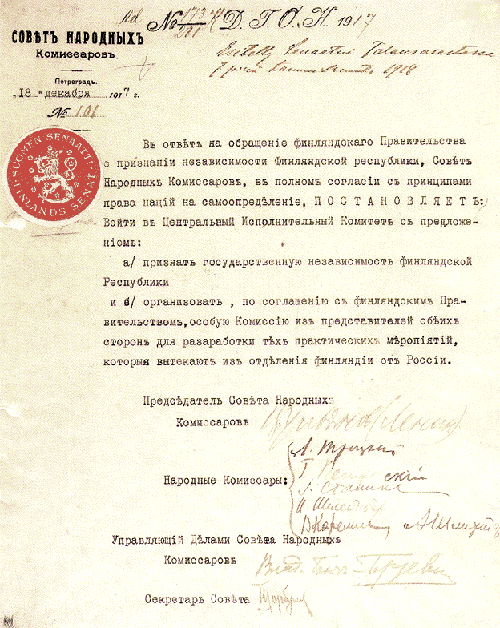

The declaration of the recognition by the Soviet of the People’s Commissars of Finnish independence, signed by Vladimir Lenin, Leon Trotsky, Grigory Petrovsky, Joseph Stalin, Isaac Steinberg, Vladimir Karelin, and Alexander Schlichter

The land which today constitutes the nation of Finland first shows evidence of human habitation at the end of the last Ice Age, around the year 9000 BC; as the glaciers retreated, human beings began to live in the far northern lands.

Iron working arrived in Finland around 500 BC and revolutionised life and agriculture. It is likely that in this period the proto-Finnish tribes, who would eventually form the core of Finnish identity, formed.

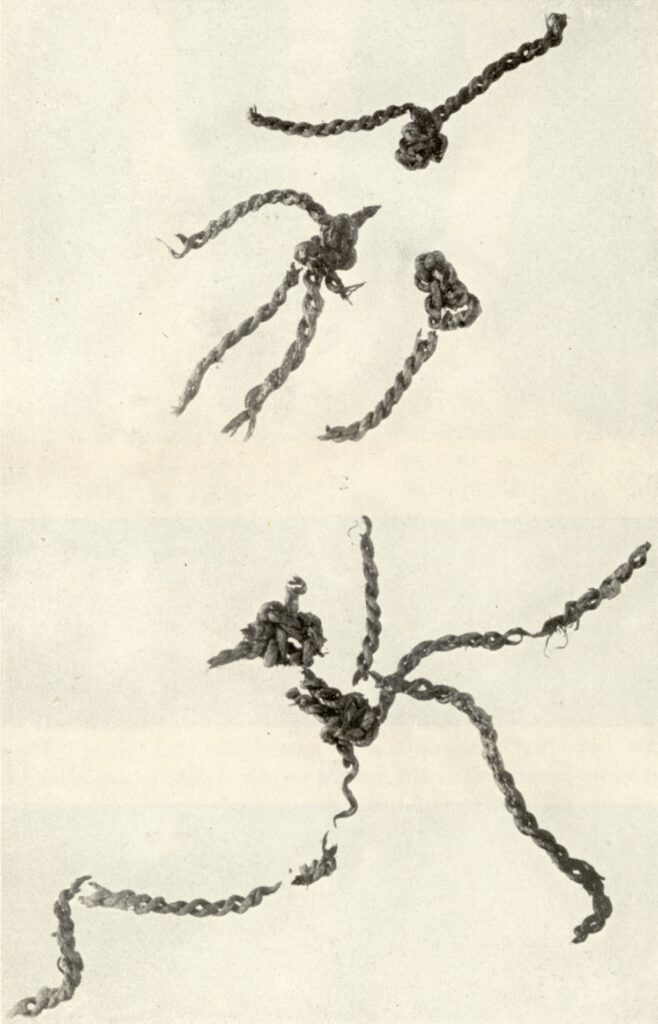

Pieces of the Antrea Net (8300 BC), the oldest-known fishing net in the world

Finland remained relatively sparsely populated and undeveloped, inhabited by various small tribal groups who shared a language and a number of religious practices.

In the 1100s, Catholic missionaries began to convert some of the Finnish people to Christianity. While there had been trade and contact between Swedes and Finns for centuries, it is around this period that Sweden began to slowly colonise the coastal regions of Finland and incorporate them into the Kingdom of Sweden.

Raids by the remaining pagan Finns would provide the justification for Swedish crusades deeper and deeper into the region and eventually the whole area was conquered by the Swedes.

The patron saint of Finland, Saint Henry, centre, is flanked on the right by Bishop Konrad Bitz and on the left by Dean Magnus Stjernkors in this illustration from the Missale Aboense (1488)

Finland would remain a part of the Kingdom of Sweden for centuries to come.

During this period, while Sweden controlled the higher levels of power in Finland, there was a high degree of local autonomy and Finnish identity was maintained.

Sweden’s attitude to Finland varied wildly over the many centuries it ruled the area. For much of this time, the Swedes saw Finland as a backwater of sparsely populated woods with strange peasants who spoke an incomprehensible language. At times the Swedes sought to assimilate the Finns into Swedish culture and root out the Finnish language.

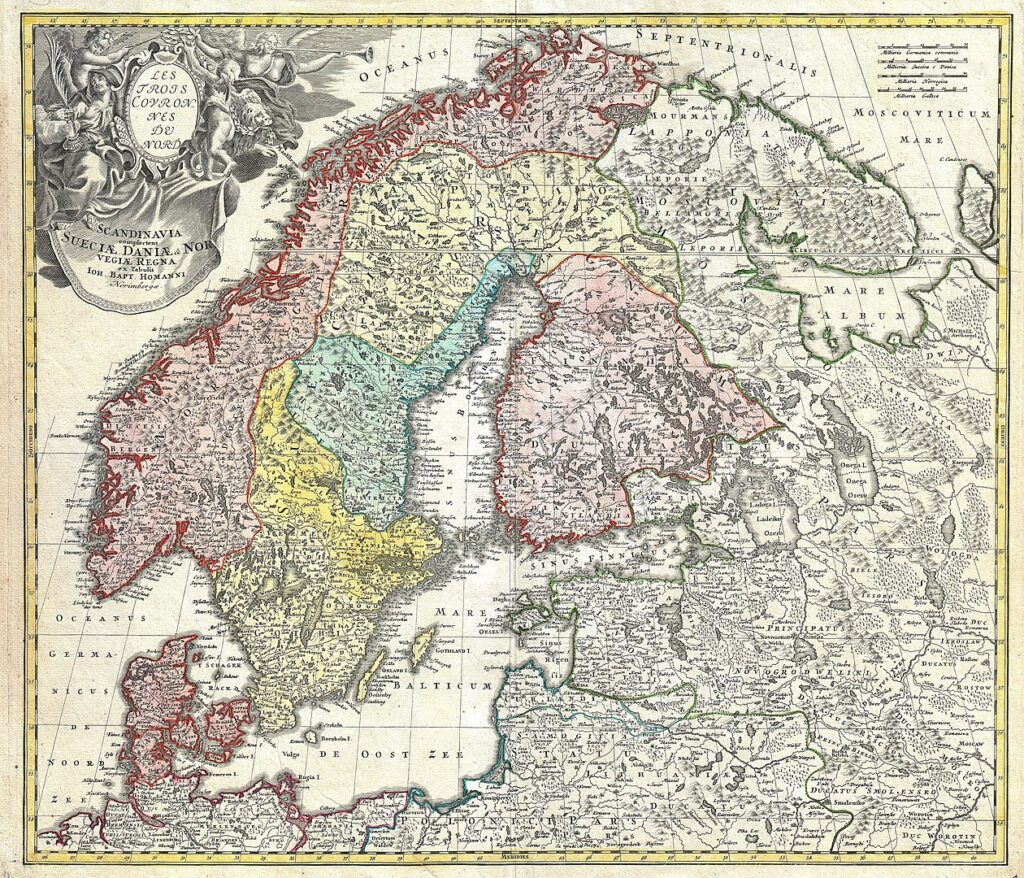

Homann’s map of 1730 of the Scandinavian Peninsula and Fennoscandia with their surrounding territories: northern Germany, northern Poland, the Baltic region, Livonia, Belarus, and parts of Northwest Russia

Starting in the late 1600s, however, the Swedes decided to take a more conciliatory approach and emphasised the unity of Swedish and Finnish identity, one kingdom with two peoples.

Everything would change, however, when Sweden lost a war with Russia in 1809 and was forced to give up control of Finland to the Russian Empire.

Russia incorporated Finland into its empire as the ‘Grand Duchy of Finland’, a region that would have more autonomy than most of the rest of the empire. Tsar Alexander I promised in the Diet of Porvoo that the religion of the Finns would not be interfered with, and Finnish identity would be secure.

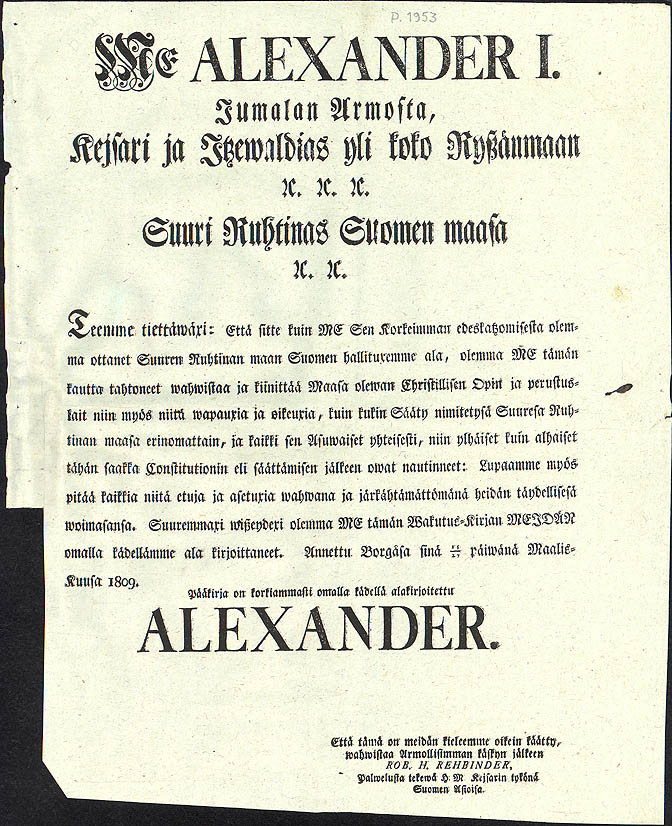

The sovereign’s pledge, the Diet of Porvoo, of 1809, printed in Finnish

Finnish autonomy was less than it had been under Sweden but was still mostly respected until 1881 when Russia began an aggressive policy of Russification.

Finnish autonomy in governance was abolished, legal provisions were enacted against Protestants in favour of the Russian Orthodox Church, press censorship was enhanced, Finns, like the rest of the Russian population, would be conscripted into the army, the language of administration was changed to Russian, and Finnish officials were replaced with Russian ones.

From this point on, Finnish nationalists began to aggressively organise for the overthrow of Russian rule in the territory.

Protesters gather in Senate Square in a demonstration against the February Manifesto in March 1899 [Axel Strandberg – Museovirastohttps://www.finna.fi/Record/hkm.HKMS000005:0000085x#image, CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=86316877]

After the revolt against the Tsar in the aftermath of the defeat by Japan in the Russo-Japanese War, Russia was forced to reform, and the Russian Constitution of 1906 created a parliament for Russia and for Finland.

However, these parliaments were largely ignored by the Tsar and in 1917 during military setbacks against the Germans in the First World War, the Tsar was overthrown and a new provisional government was set up.

The provisional government was very unstable, prompting the Finnish parliament to seize the opportunity created by the weakened central authority to begin asserting its own authority. The October Revolution launched by the Bolsheviks in late 1917 overthrew the provisional government and threw the entire Russian Empire into civil war.

Prime Minister P E Svinhufvud, seated at the head of the table, presides over the first government of independent Finland

In late November 1917 Finnish politician Pehr Evind Svinhufvud formed a de facto government of Finland which would declare independence on 4 December 1917. When the Finnish parliament approved this declaration two days later, an independent Finnish nation state was born.

As they had their hands full dealing with enemies on all sides, the Bolsheviks accepted Finnish independence on 31 December 1917.

The new Finnish government was fairly conservative and anti-communist and soon was in conflict with the communist parts of the society.

In January 1918, a civil war broke out between the Reds and Whites in Finland, the Reds being supported, and supplied with weapons, by the Soviets. The Whites were supported by Sweden and later by the Germans, who proved decisive in swinging the balance of power behind the White government.

A Finnish machine-gun crew during the Winter War

Finland would be consolidated by the White government and would remain anti-communist. Decades later, however, Finland would once again face off against the communists in the Winter War of 1940.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend