In acknowledgement of the traditional ‘silly season’, inspired by the rereading of a favourite ‘Christmas’ poem by TS Eliot and a recent presentation by former IRR CEO Frans Cronje, and in the spirit of the Spectator’s customary gift of a free short story for its readers at Christmas (this year’s is by Lee Child), I offer up this free, albeit incomplete, snippet of a story for Daily Friend readers.

(Clues to the poem’s title are to be found in the text).

They had a hard time of it as they headed for the border the morning after the blow of the night before. The citizens were hostile and the towns unfriendly.

The villagers were dirty and charged high prices for the fuel they had reluctantly supplied for cash only. Or maybe it had always been expensive. It was hard to know as they had not paid for it themselves for some time.

Only a few of the occupants of the no longer so shiny cavalcade of luxury vehicles had had the foresight to bring the cash money they’d stashed in items of furniture distributed among their many houses and homes.

A few who were cashless but digitally proficient had also discovered that e-walleting money to themselves didn’t help. They couldn’t use any ATM en route to withdraw that money because of load-shedding.

In the end those that had money on them were forced to stump up for those that didn’t. There was some grumbling about this, but in the end, they agreed reluctantly to share with the less fortunate and instructed the various drivers to conserve petrol by driving as slowly as possible.

Many were also running out of battery power in their cell phones, and there were squabbles over who could have a chance to charge their phone because they had too few cars for too many people.

They’d been slow in getting going because Fikile had insisted on nipping home to fetch a new leisure outfit to wear on the journey and had taken the basement garage door key with him.

Strangely quiet

Time had also been wasted in the dawn hours by trying to get hold of foreign friends. But it seemed no one was home in Beijing and Moscow. Then they’d had to kick their heels on the pavement outside the results venue until the cars were brought out and round. It was strangely quiet without the usual media pack.

Once on the road Pemmy had set them back some more by leaving her latest headgear behind in one of the washrooms where they’d all stopped for a necessary comfort break. She’d insisted they all go back and look for it and surprisingly it was still there, where it had been mistaken for one of the vibrant flower arrangements for which the ladies’ washroom was well-known.

What had shocked them most on the journey was that their abandonment by almost all of the VIP protection squad meant they were unable to retaliate when a couple of people in the traffic gave them the middle finger as they overtook them.

It was hot and stuffy pressed up against comrade brothers and sisters in the back and front seats of cars they’d normally occupied only with an executive assistant or anonymous companion and, of course, a driver. They were also hungry and thirsty.

While some among them had remembered to throw in a bottle or two from the dwindling stocks of their favourite tipple stashed in the drawers of their empty filing cabinets or the free bottles of water that littered abandoned conference rooms, the veterans, too accustomed to having their every need met by others, had departed empty-handed.

A few of the more substantial senior women had had the foresight to pack some leftovers from the IEC buffet into their LV and Birkin bags and covetous eyes were being cast at these nibbles.

The fast-food chicken outlets they’d hoped to stop at on their way had simply closed their doors and shuttered their windows as they spotted the strangely quiet and minimalist blue light brigade approaching. They’d been forced to drive on each time.

Palatial homes on the slopes

Soon after they crossed into Limpopo they lost a couple of honourable members who peeled off, abandoning the snail-paced convoy ̶ and probably the cause ̶ and headed for their ranches and palatial homes on the slopes.

Three glamorous young influencers who’d been at the awaiting-results parties and had travelled perched on the laps of the deputy and other ‘charmzas’ became refractory. They were reporting little interest in their bravado posts on social media or any response at all from their fickle followers, and whined to be dropped off at the roadside.

Even the strong of mind and body among the cabinet were beginning to feel the hard and bitter agony of their defeat.

They knew they had few resources left to count on beside the proverbial fax machine in Fikile’s boot which the Sheriff, only a few months earlier, had declined to include in his Luthuli House asset inventory.

After many hours on the road the line of cars cruised slowly into the parking lot of a budget Musina motel.

They’d been lucky, thanks to Uncle Gweezy’s wife’s credit card, to secure satisfactory last-minute accommodation (although certainly not the government handbook-required 4-star-and-up standard) in this rambling, slightly tattered establishment.

Mandoza’s Nkalakatha was playing on the car radio as they pulled in. An elder among them recalled one of the opposition parties had used this very song twenty or so years ago for the entry of a leader at one of their congresses. He demanded irritably that it be switched off.

Sticky, close confines

The leadership hauled themselves out of the sticky, close confines and stood around disoriented as the sun began to set over the dusty lot.

The last of their faithful flunkies had secured a booking for a large tent, chairs and tables to be delivered here, just before abandoning them to their own devices. These were scheduled to be delivered in the morning if the payment had gone through.

Tomorrow, tucked away in this far corner of the land, they would rise renewed and refreshed and be ready to regroup; to make plans; do deals with whoever was interested and strike bargains with the victors. They would ‘fight back’. (Or something along those metaphorical lines but, perhaps, not quite in those words).

They could also, perhaps, ask allies across the river to the north for survival tips.

There were certainly several among them who regretted the folly of not acting on the expert advice of their northern allies earlier, when they’d begun seeing the writing on the wall in the months prior to the elections.

But it was hard to break a habit of several decades of not listening to anyone else. And to be honest, many of them admitted secretly to themselves, it was also highly unlikely they would have been able to implement even that last ditch, large-scale, plan.

They stared at the three trees on the horizon and shuffled off to their rooms, their unease about the future growing.

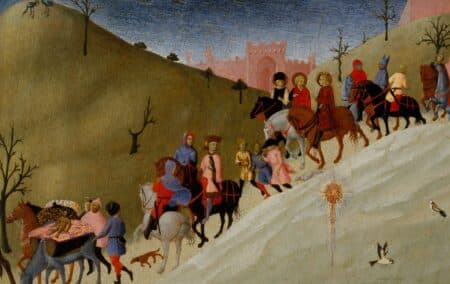

[Image: The Journey of the Magi, Stefano di Giovanni (1392–1450)]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend