The character of Santa Claus has an odd history. We celebrate an invented image popularised by Coca-Cola.

A couple of years ago, a Catholic diocese in Italy was forced to apologise because one of its bishops, Monsignor Antonio Stagliano, said Santa Claus isn’t real.

Their reasoning wasn’t entirely baseless: ‘…Santa Claus is an effective image to convey the importance of giving, generosity, sharing. But when this image loses its meaning, you see Santa Claus aka consumerism, the desire to own, buy, buy and buy again, then you have to revalue it by giving it a new meaning.’

It is certainly true that Christmas is a massive consumer-fest. Children feel entitled to expensive presents, and few children learn anything at all about giving.

Like a good free-marketeer, I happily grant companies the right to part fools from their thirteenth cheques, and equally happily grant consumers the right to buy banalities, but I – also like a good free-marketeer – can choose not to fall for the marketing hype.

Personally – although I’ve never cruelly disabused a child of cherished notions – I have qualms about deceiving children into believing that non-existent entities are real. I think it impairs critical thinking. If you can believe the patently untrue, you can believe anything.

I also cannot imagine that the notion of a fat stranger breaking into your home to eat cookies and deliver presents is any more wholesome than the belief that parents care so much for their children that they would treat them to a lovely Christmas.

Philosophical issues aside, however, the image we have of Santa Claus is of dubious provenance.

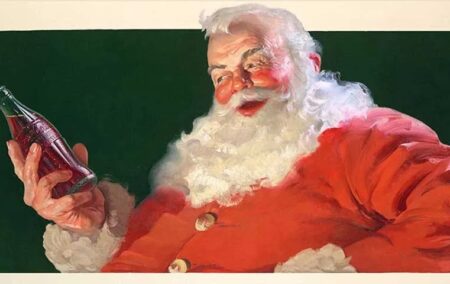

Coca-Cola

The good Monsignor Stagliano pointed out that ‘Santa doesn’t exist and that his red costume was created by the Coca-Cola company for publicity’.

Although the company denies having created the character, it certainly agrees that the portly, jolly, elderly fellow with a long white beard and a red suit was created by an illustrator, Haddon Sundblom, whom the company commissioned to create advertising images featuring Santa.

Stagliano, then, is quite correct. Coca-Cola didn’t invent Santa Claus, but it certainly popularised him and gave him his modern clothing and image:

Coca-Cola had used Santa Claus in advertising since the 1920s. In its history of the Coca-Cola Santas, the company says that its early renditions were inspired by the drawings of Thomas Nast:

Sundblom, commissioned in 1931, modelled Santa on a friend, a retired salesman, and when that friend died, he turned to self-portraiture.

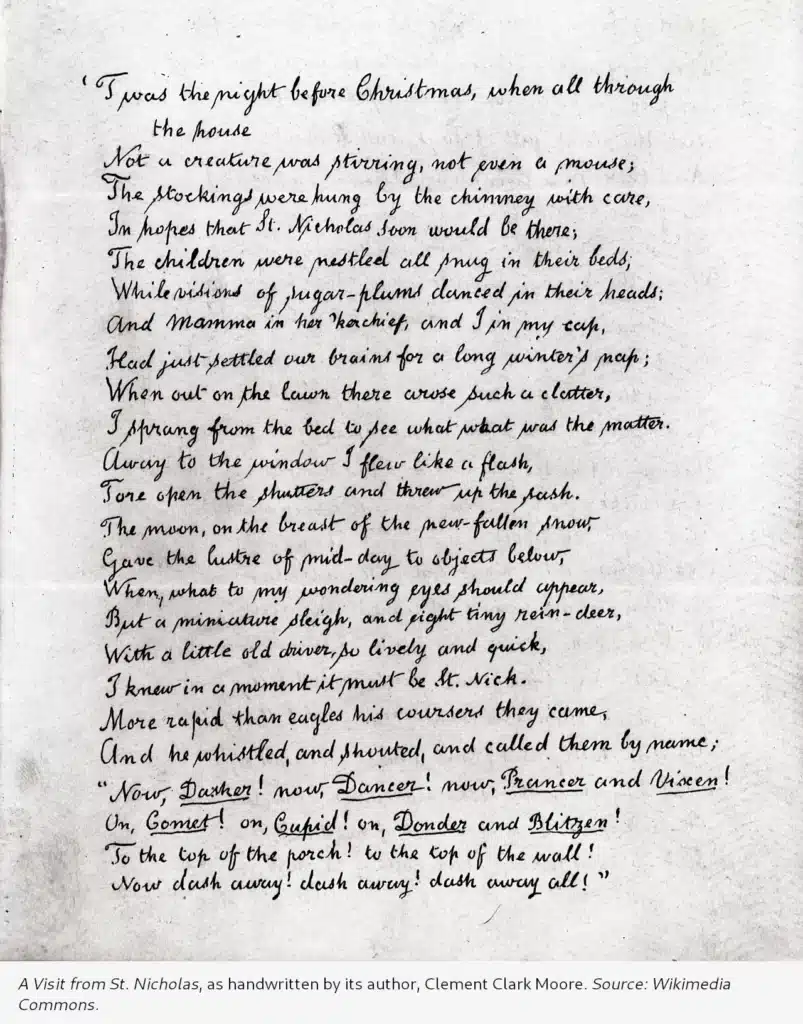

Sundblom relied also upon an 1823 rhyme – I hesitate to call it poetry – by an American author, Clement Clarke Moore, entitled A Visit from St. Nicholas. Better known as The Night Before Christmas, the opening lines are here rendered in the author’s own handwriting:

Moore, Nast, Sundblom and Coca-Cola, then, form a minimal basis for the American tradition of a ‘jolly old elf’ with a conspiratorial finger aside his nose, pulled by reindeer and carrying a toy bag, who despite his evident obesity and the pristine white fur trim on his red suit climbs down sooty chimneys to fill stockings and consume his reward of cookies and milk.

Stagliano was quite right to point all this out. Sorry, disillusioned children.

Father Christmas

Moore and his New World compatriots drew on a number of traditions from the Old World.

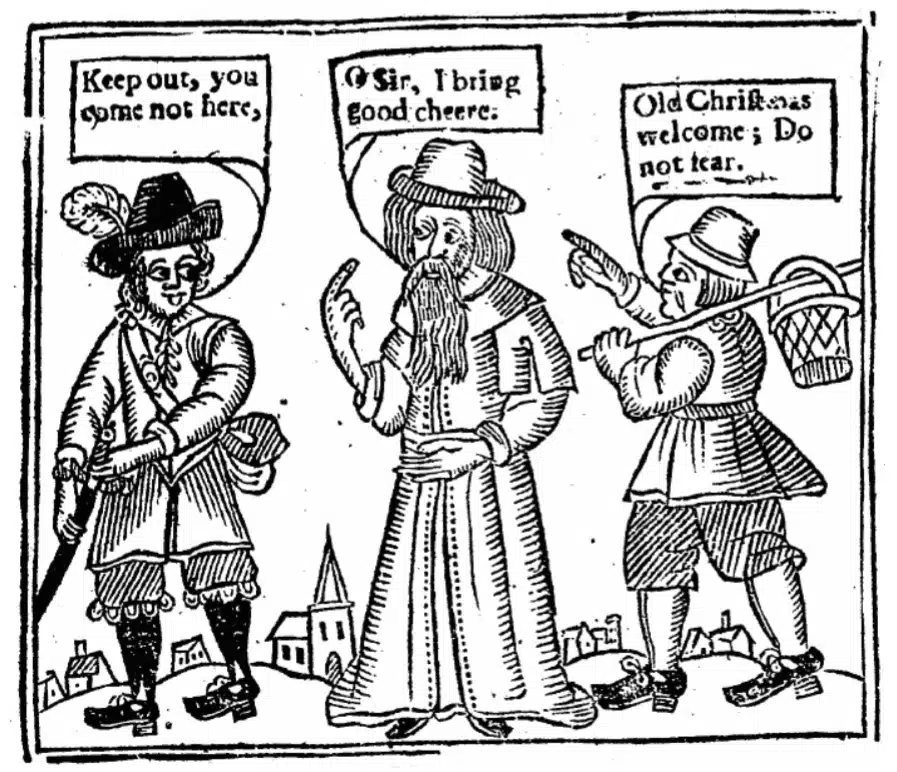

There’s Father Christmas, variously described as Sir, Lord, Captain or Prince Christmas, who was an English personification of the traditional mid-winter feast which became synonymous with Christmas.

The folkloric character, and indeed the Christmas celebration itself, were rejected by Protestant Puritans in the 17th century, who thought the tradition too popish to permit, but Father Christmas prevailed, and was eventually accepted into the Protestant fold, associated with Christmas Day on 25 December.

A cartoon by John Taylor from 1652 depicts The Vindication of Christmas:

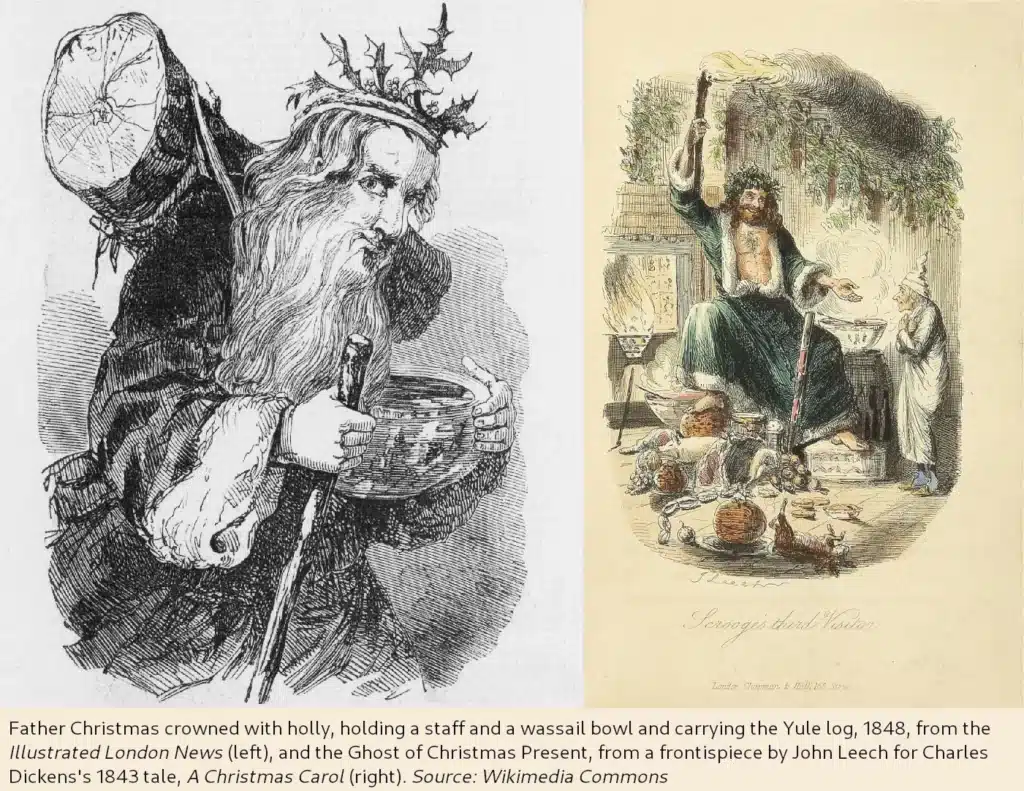

By the 19th century, the English Father Christmas was variously depicted as a wise old man carrying a Yule log, or a vivacious younger man in a green robe, but fat and red he wasn’t.

A notable feature of the English Father Christmas is that while he was associated with feasting, good cheer, songs and revels, he was not associated with children or bringing presents.

That association only emerged during the Victorian era, partly inspired by the re-importation of the American example. By the early 20th century, Father Christmas and Santa Claus had become virtually synonymous.

Sinterklaas

Before the establishment of the Anglican Church by Henry VIII, Father Christmas was celebrated on 6 December. This corresponds to the feast day of St. Nicholas, which developed a rich tradition in northern Europe, where it is also known as Sinterklaas.

This depiction also garbs the main character in red, although his attire is now recognisably Catholic, complete with Christian crosses, a mitre and a crooked shepherd’s staff.

In the Netherlands, Sinterklaas is associated with children and gift-giving on 5 December, the eve of his name day, while western Germany, Belgium, Luxembourg, northern France, Romania, Poland and Hungary do their gift-giving on the morning of 6 December.

According to legend, he arrives by boat from Spain, and rides a mottled white-and-gray horse across the roofs. Instead of stockings, Europeans put out shoes, and instead of milk and cookies for Santa, they leave hay, carrots and apples for the horse.

Accompanying Sinterklaas, traditionally, is his now-controversial helper or servant, Black Pete. Modern interpretations daub Petes in varying colours, or put Pete’s swarthiness down to the fact that he is a chimney-sweep who goes down chimneys to deliver presents.

Traditionally, however, Black Pete is played by a white man in blackface, and many older illustrations are outright racist stereotypes. Even those that aren’t make it clear that Pete is a black servant or slave, such as this illustration in Jan Schenkman’s 1850 book, St. Nikolaas en zijn knecht (St. Nicholas and his servant):

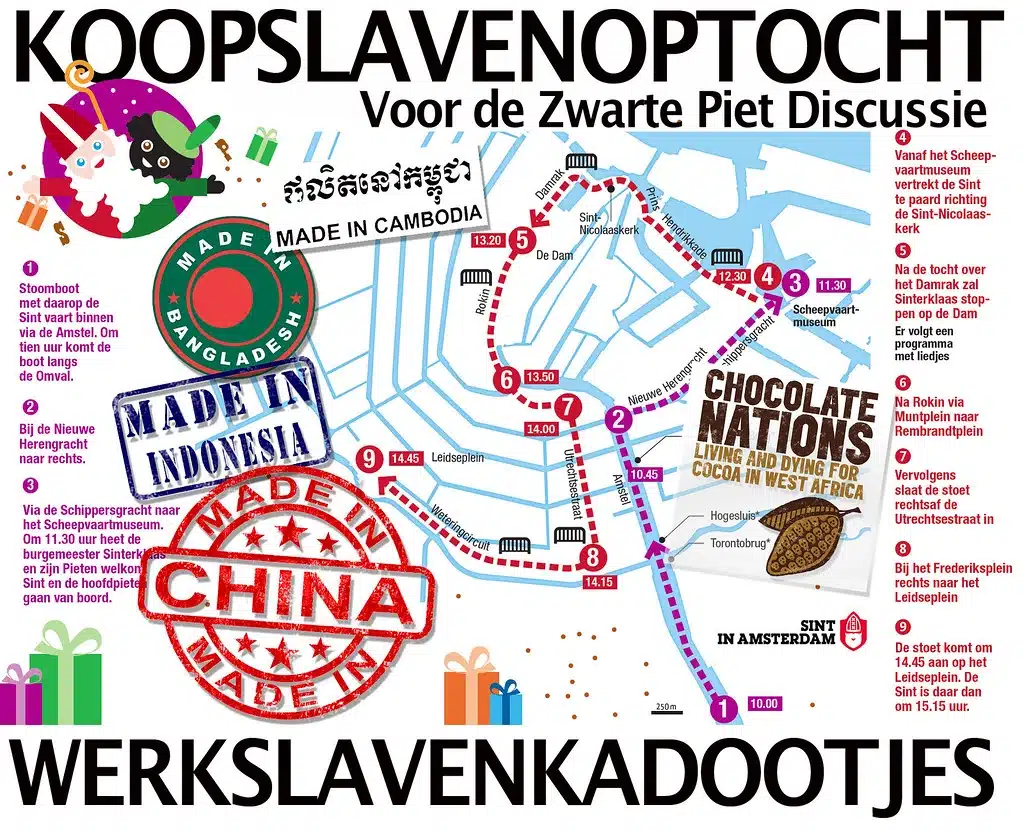

While reluctant to reject well-established traditions, the racist depiction of Black Pete has been a matter of controversy and introspection for the Europeans, as exemplified in a protest poster which annotates the route of a Sinterklaas procession through the canals of Amsterdam with the words, ‘Slave Trade Parade / Slave Labour Gifts’:

Still, despite the controversy, the northern European tradition clearly separates the Day of St. Nicholas, associated with children, fun, feasting and presents, from Christmas, which is celebrated as a more solemn and splendid religious festival.

St. Nicholas

Which brings us to the real St. Nicholas, whose celebration Bishop Stagliano was trying, perhaps foolishly, to defend.

St. Nicholas did not come from Spain, but from Myra, which became the modern-day Demre, in Turkey. Contrary to the European legend, 6 December was not the anniversary of his birth, but of his death, in the year 343 CE.

He is celebrated not only for his alleged miracles, but also for his habit of secretly giving gifts to the poor and desperate. Most notably, he is said to have saved three girls from prostitution by secretly depositing three bags of gold coins through the window of their house, so that their father could pay dowries for each of them. (How his identity was discovered so that he could be venerated for this generous act of charity is a mystery.)

In the Catholic tradition, he is the patron saint of sailors, merchants, archers, repentant thieves, children, brewers, pawnbrokers, unmarried people, and students.

St. Nicholas has been portrayed wearing various colours, including not only red, but blue, green, and gold.

The modern Santa, created in large part by Coca-Cola, is very far removed from the original patron saint of children.

Stagliano is right

In part, I agree with Stagliano. If I were a Christian, I would consider the modern, commercialised Christmas with its fat, red Santa Claus to be corruption of the true meaning of Christmas.

While Stagliano is concerned with the celebration of St. Nicholas, I (were I Christian) would be concerned with the celebration of the birth of Jesus.

I much prefer the way the northern Europeans have separated the two celebrations: keep Christmas as a religious holiday focused on the birth of Christ for those who care to celebrate it, and dedicate a separate holiday to giving gifts to children and giving charity to the poor.

What we have now is the worst of all possible worlds. Whether you’re religious or not, the crass commercialisation of Christmas and the greed it instills for more and bigger gifts is simply obnoxious.

It has become an exercise in over-spending on expensive presents that keep the kids up with the Joneses’ kids, and over-priced food and drink which in this economy few can really afford.

Not being religious, I don’t much care for the true meaning of Christmas, or the true meaning of St. Nicholas. I care for family, and I care about charity, but I’ll be damned if I’m going to let Coca-Cola instruct me how to celebrate either of them.

PS. The author has taken a rare holiday, and will be unable to respond to comments. Enjoy not being argued with for a while.

[Image: Santa Claus, as drawn by Haddon Sundblom for Coca-Cola. Source: Coca-Cola]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend