CNN appears upset that Steve Ballmer will earn $1 billion a year ‘for doing nothing’. Here’s why he deserves it.

At 67 years old, Steve Ballmer is sitting pretty. He was the jumping, screaming, sweating CEO of Microsoft between 2000 and 2014, and now collects dividends from the company.

In September, Microsoft raised its quarterly dividend from 68c/share to 75c/share, a 10% increase. This continues a ten-year trend of growing dividends paid to shareholders.

Steve Ballmer is one of those shareholders, and CNN’s ‘economy explainer reporter’, Elisabeth Buchwald, thinks that it’s news that ‘Steve Ballmer is set to make $1 billion a year for doing nothing’.

Presumably her editors were less enthusiastic about the implied disapproval in the headline, choosing to carry the story on 27 December, in the dead of the festive season.

‘Simply owning the stock’

Ballmer owns 4% of Microsoft, which equates to 333.2 million shares, which at a dividend 75c/share/quarter, or $3 for the full year, works out to $999 600 000 per year.

‘That’s for simply owning the stock — regardless of how it performs,’ Buchwald writes, with ill-disguised distaste.

This is simply wrong. Dividends are paid by companies that perform well and make reliable profits. Microsoft is such a company, and Ballmer had a big hand in making it so. Dividends are not paid ‘regardless of how it performs’.

Buchwald is young, which may explain her disapproval of people earning a lot more than she does. She only graduated in 2019, and has been at CNN for only nine months. She’s likely still brimming with egalitarian fantasies and socialist idealism, as inexperienced young people often are. Perhaps she’ll learn.

She does add that Ballmer will pay a fat 20% tax on this dividend, amounting to $200 million, and that other people also earn money from owning stocks that pay dividends.

Yet she doesn’t seem to have a clue why people who own shares in companies merit the dividends those companies pay.

Return on investment

Ballmer hasn’t done nothing to earn that dividend. He owns the shares. He could sell them, and withdraw all that capital from Microsoft.

The company’s share price hit an all-time-high of $382.70 on 28 November 2023, and last closed at $374.07. Assuming he could dump his entire 333.2 million shares at that price (which he can’t, because as soon as he starts unloading, the price will collapse) he would make $124.6 billion from the transaction.

Even if he realised only half that, $62 billion in cash is surely worth more to a 67-year-old than $1 billion per year.

Instead, Ballmer chooses to leave that capital invested in Microsoft, where it is being used to make things that Microsoft customers buy, and to pay the 221 000 people that work for it.

The general case is simple. If a bank lends you money, it is going to charge interest. It won’t do so for free.

Why would someone invest in a company for free? If an investor acquires shares in a company, then, if the company makes sufficient profit and the shareholders agree it doesn’t need to reinvest that profit or use it for acquisitions, the company pays the profits back to the investor.

People don’t invest their capital without any expectation of a return. They either want the share price to go up, or they want the company to be profitable and pay dividends, or both. Failing that, investors will sell their shares and take their capital somewhere where it can be more productively used.

Capital allocation

This is a basic principle of free markets: this is how the market allocates scarce capital between a potentially infinite number of uses. Buchwald, who claims to have earned a degree in economics and international business magna cum laude, ought to know this.

So, simply by leaving his wealth invested in Microsoft, Ballmer is doing enough to justify earning a 0.9% return on his investment per year.

If that yield sounds low, that is because it is. ‘Microsoft is among the lowest-yielding members of the Dow Jones Industrial Average that pay dividends, as only Visa Inc. and Apple Inc. yield less,’ reported Emily Bary for MarketWatch when the new dividend was announced.

So why Buchwald bullies Ballmer in particular is a mystery. Anyone with similar stakes in similarly sized, dividend-paying companies would receive similar payouts for supposedly ‘doing nothing’ (except make their capital available, at risk, to the company).

Mr Monkey Boy

But what else did ‘doing nothing’ entail?

Look, I’ve always been a critic of the company, and of Ballmer. I don’t use Microsoft products. My friend, Duncan McLeod, the editor of TechCentral, assures me that Microsoft products are better than they once were, but I swore off it 20 years ago and am not about to return.

Ballmer’s so-called Mr Monkey Boy dance in 2000, at which he declared, ‘I love this company’, to me epitomised the worst of brash American marketing excess. It was the dot com hype personified.

Only today did I discover that at 21 seconds into the now-famous video, Ballmer sprains his ankle and screams in pain, but hardly misses a beat. He really did love that company.

He was that kind of executive. He was a corporate evangelist. His vocal chords once needed surgery from excessive shouting. He was bold, driven, loud and bald. He was the exact opposite, caricature-wise, of Bill Gates, the soft-spoken nerd. They had little in common, except for being exceptionally smart.

Ballmer joined Microsoft in 1980, becoming only its 30th employee and its first business manager. He was a Harvard dormmate of Gates, who co-founded Microsoft with Paul Allen in 1975.

Poor boy from a poor family

Unlike Gates, Ballmer did not come from money. He was the son of an immigrant who worked as an accountant at the Ford Motor Company in Detroit.

In addition to his salary, Ballmer was offered shares in the tiny, unproven company.

Microsoft would release Xenix, a Microsoft Unix clone for microcomputers, and MS-DOS, a CP/M clone it bought and hacked for IBM’s new PC, in the year Ballmer joined. When Microsoft was incorporated in 1981, Ballmer’s stake amounted to 8%.

In 2003, Ballmer sold half of his stake for less than $1 billion, but retained the other 4%.

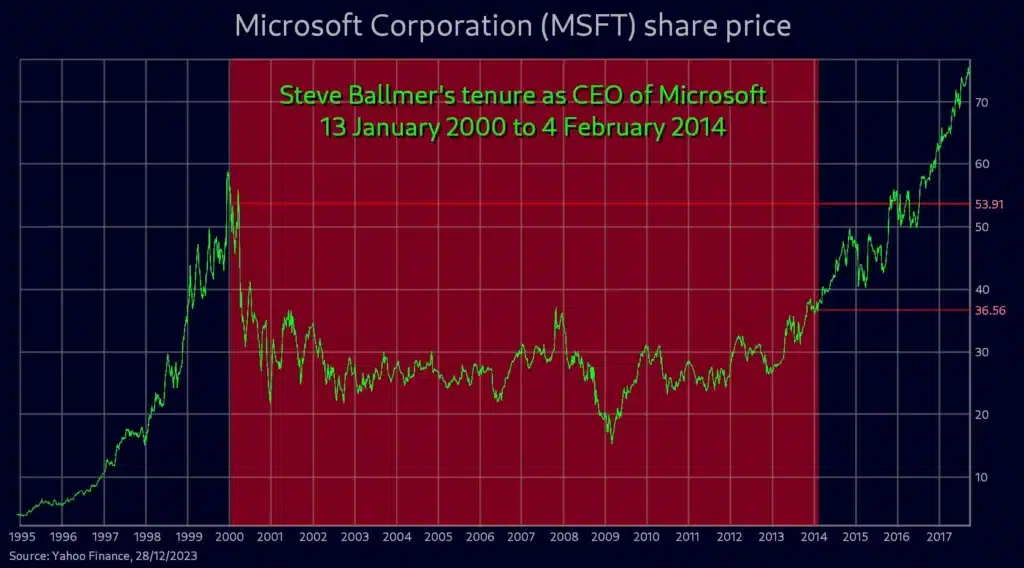

Critics also point out that Microsoft’s stock price did nothing while Ballmer was CEO. On the contrary, it was one third lower when he left than when he started.

That’s not exactly fair, however. He took over only two weeks after the share’s dot-com-boom high of $59.56. Everyone crashed hard. Microsoft’s share price did no worse than the Dow Jones, or the Nasdaq, or the S&P500.

And share price isn’t the be-all-and-end-all of corporate performance.

‘Safe, profitable’

On Ballmer’s watch, Microsoft launched several commercial duds or critical failures, like the Zune media player, the Windows Phone, the Surface touch-screen tabletop, and Windows Vista. It was heavily criticised for failing to capitalise on smart phones, smart watches, smart cars and cloud services.

Yet Ballmer also led a long campaign to success in the enterprise market, with major products such as Windows Server, SQL Service, Exchange, SharePoint, and Dynamics CRM.

He earned a reputation for taking the ‘safe, profitable route’ over innovation. Under his leadership, Microsoft increased revenue from $25 billion to $70 billion, or more than 10% growth per year. It raised net income from $5 billion to $23 billion. The company’s gross profit margin of 75% was double that of its major rivals.

Ballmer also introduced the company’s first dividends in 2003, which by the end of 2004 had become regular quarterly events.

The reign of Steve Ballmer was perhaps not as spectacular as those of his predecessor, Gates, or of his brilliant successor, Satya Nadella, but he captained a steady ship through a tough time not only for the company, but for the technology sector more widely.

Ballmer resigned from Microsoft in 2014. He hasn’t done nothing to earn that dividend. He dedicated 34 years of his life in loyal service to the company, and had a major hand in growing it from an embryonic startup to a global behemoth.

He also deserves at least some of the credit for the money that literally billions of Microsoft customers made by using its products. If you can get your products as widely used as Microsoft did, you surely deserve a commensurate reward.

Philanthropy

In her eagerness to set the eat-the-rich mob upon Ballmer, Buchwald neglects to mention that Steve and his wife, Connie, founded the Ballmer Group after he retired from Microsoft.

Established to manage the couple’s wealth, the Ballmer Group is a philanthropic investment company focused on helping disadvantaged children, especially those from the lowest socio-economic circumstances, to climb the economic ladder. It does so by funding organisations that have a proven record of reducing systemic inequality, or providing services that strengthen communities.

Ballmer has earned the $1 billion per year he gets for ‘doing nothing’, and at 67, deserves to be sitting on a tropical beach sipping Piña Coladas. If he frittered it all away on sports cars, expensive wine and yacht parties, he’d be perfectly justified to do so.

Instead, he is spending his wealth on uplifting the poorest of the poor.

Buchwald’s attack on his wealth is not only a denunciation of the principle that successful investment of time and money merits reward, but is also an attack on the philanthropy that directs Ballmer’s personal wealth to poor youngsters, black businesses, and black-led non-profits addressing economic mobility.

Ballmer’s products have benefited billions, and his charity has benefited millions.

One wonders what young Buchwald, with her magna cum laude economics degree and her four years’ experience as a personal finance reporter, has ever done for the poor, or for anyone else.

[Image: Steve Ballmer, doing nothing, in 2008. Source: Wikimedia Commons]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend