This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

11th February 1979 – The Iranian Revolution establishes an Islamic theocracy under the leadership of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini

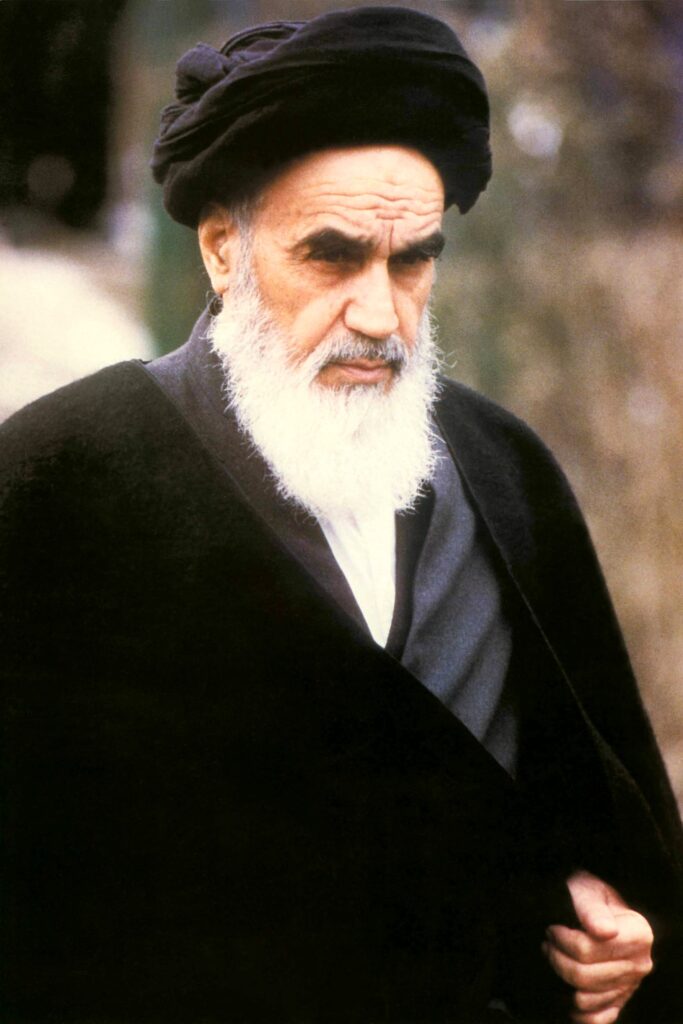

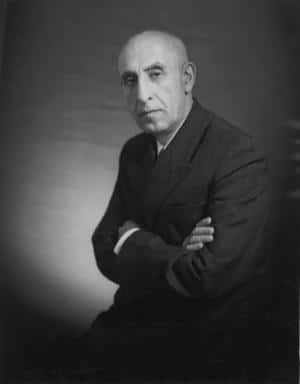

Ruhollah Khomeini, the first supreme leader of Iran

By the mid-20th century, Iran had lived through over a century of difficult times.

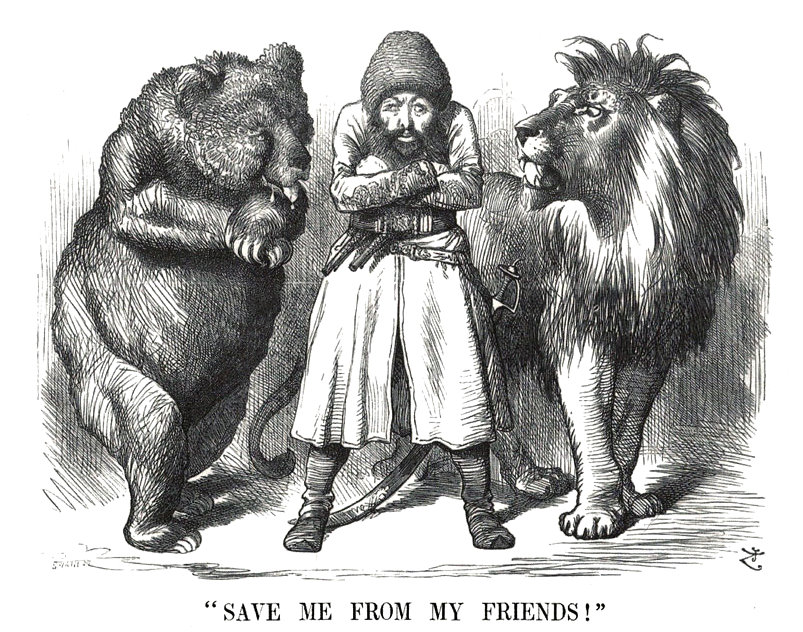

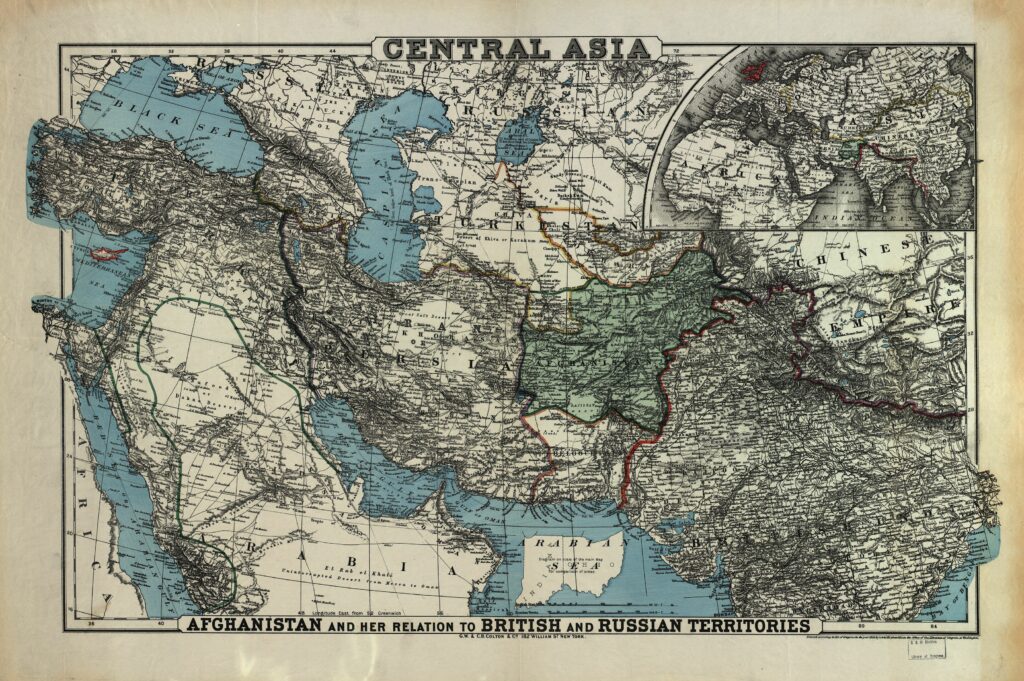

In the early 1800s the Turkic rulers of the Qajar dynasty of the Persian Empire had lost wars against the Russian Empire, being forced to cede important territory. Persia’s population was swollen by large numbers of Muslims expelled by the Russians from the Caucasus in the mid-1860s, and the once mighty empire became the plaything of British and Russian interests, as the two powers battled for control over Central Asia in the ‘Great Game’.

Political cartoon of the ‘Great Game’ era, depicting the Afghan Emir Sher Ali with his ‘friends’ the Russian Bear and British Lion

In 1901, British prospectors began searching for oil, discovering deposits in 1908. This would make southern Persia even more important to the British, who would become heavily involved in the production of oil in the country.

The north of Persia was dominated by Russia, which, around 1910, even had garrisons of troops around the Caspian Sea.

American map of 1885 of Central Asia, Afghanistan, and British and Russian territories

At the start of the First World War, the Persian monarchs declared that Persia would remain strictly neutral. The Ottoman Empire, seeing Persia as little more than a puppet of their Russian and British enemies, invaded the country.

The subsequent occupation of the country by British, Russian, and Ottoman troops, as they fought for control of Persia, shattered the legitimacy and prestige of the Qajar monarchs, and, in 1921, a Persian army officer from the shores of the Caspian Sea, overthrew the monarchy in a military coup.

Reza Pahlavi behind a machine gun

The officer came to be known as Reza Shah Pahlavi, and founded the Pahlavi dynasty of Iran. Pahlavi was the first Persian dynasty to rule the country since the fall of the Safavid dynasty in 1736 to Turkic warlords.

Coronation of Reza Shah Pahlavi

The new king, or Shah, set about a radical modernisation programme, with inspiration from Kemal Ataturk’s reforms in Turkey.

Reza Shah with Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

He also aggressively attempted to Persianise the country’s population, which at the time was split into many ethnic groups, such as Kurds, Turkmen and Baloch. Persia was also at the time dominated by tribal rulers and the well-established Shia clergy. The modernisation reforms were opposed by both of these groups.

Reza Shah opening a railway station

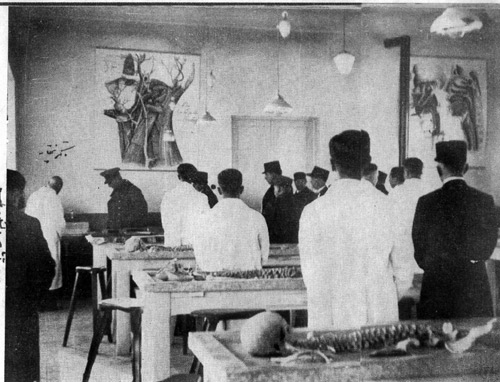

During the Shah’s reign, railroads were built, the first modern university in Persia was constructed and major road networks laid down. Education was made compulsory for both men and women, and religious schools were largely closed down.

The Shah at the opening ceremony of the University of Tehran’s Faculty of Medicine

Land was confiscated from tribal leaders and the clergy. Some forms of traditional dress were banned, and aspects of the country considered ‘backward’ were banned from being photographed.

The Shah also courted favour with the Jewish population of Persia, even becoming the first monarch in Persian history to pray at a synagogue.

In 1935, the Shah launched a campaign to change the country’s name abroad from Persia, as it was known in the West, to Iran, the name which local peoples had long used to refer to the country.

The Shah also attempted to weaken British and Russian (now Soviet) influence in the country, and had some modest success. The British, however, still maintained large influence over the oil industry.

During the Second World War, the British and then the Soviets, became worried that the Iranians were drifting into the German sphere of influence. The British feared the loss of their oil facilities in Iran, which were vital to their war effort. In light of this, in 1941, the British and Soviets launched an invasion of Iran, and quickly occupied the country, much as they had in the First World War.

The Shah was forced to abdicate in favour of his son Mohammad Reza Pahlavi; the exiled ex-Shah would die in 1944 in Johannesburg.

Reza Shah’s funeral in Tehran

The British had initially wanted to place the Qajar dynasty back in power, but the heir to the Qajar family was a British naval officer who didn’t speak Persian and so the British accepted Mohammad.

Crown Prince Mohammad Reza in 1939

Mohammad privately felt his father had ruled too crudely and too brutally, but would publicly praise his rule as enlightened. At the end of the Second World War, the Soviets would sponsor a rival puppet government of Iran in the north of the country, and out of fear of being overthrown by this government, the Shah drifted towards the West.

Mohammad Shah would grow distant from a number of his prime ministers who he felt were too close to the Soviets. In 1951 Mohammad Mosaddegh, became prime minister and committed to nationalising the Iran oil reserves, seizing them from the British.

Mohammad Mosaddegh

Fears among the Shah’s household and some elements of the army, that Mosaddegh was a Soviet puppet saw them begin to plot against him. The British and Americans worried that Mosaddegh would lock the West out of the oil fields and align Iran with the Soviet Union, and this saw them collaborate with army officers and the Shah to dismiss Mosaddegh from government and replace him with someone more friendly to their interests, General Fazlollah Zahedi.

Fazlollah Zahedi

The coup launched in 1953 initially failed and the Shah fled the country.

The Communists in Iran however quickly fell out with Mosaddegh and began rioting, seeking his removal. The clergy decided that Mosaddegh and the communists were a threat to them and so sided with the Shah.

The army would decide to act against Mosaddegh and the Shah returned to Iran; Mosaddegh was charged with fomenting a coup, and for refusing the Shah’s instruction that he be dismissed, and Zahedi became prime minister. Mosaddegh was found guilty but had his sentence commuted by the Shah to three years, down from life in prison.

The Shah was, for a time, essentially a puppet of Zahedi, acting as little more than a figurehead to legitimise the powerful general. However, he would eventually manage to play the Iranian elites off each other and returned to power in 1955 to preside over the country as its authoritarian leader.

In the aftermath, the Shah sought to grow his popularity with the people and invited many left-wing intellectuals into his court to advise him on how to modernise the country and win popular support.

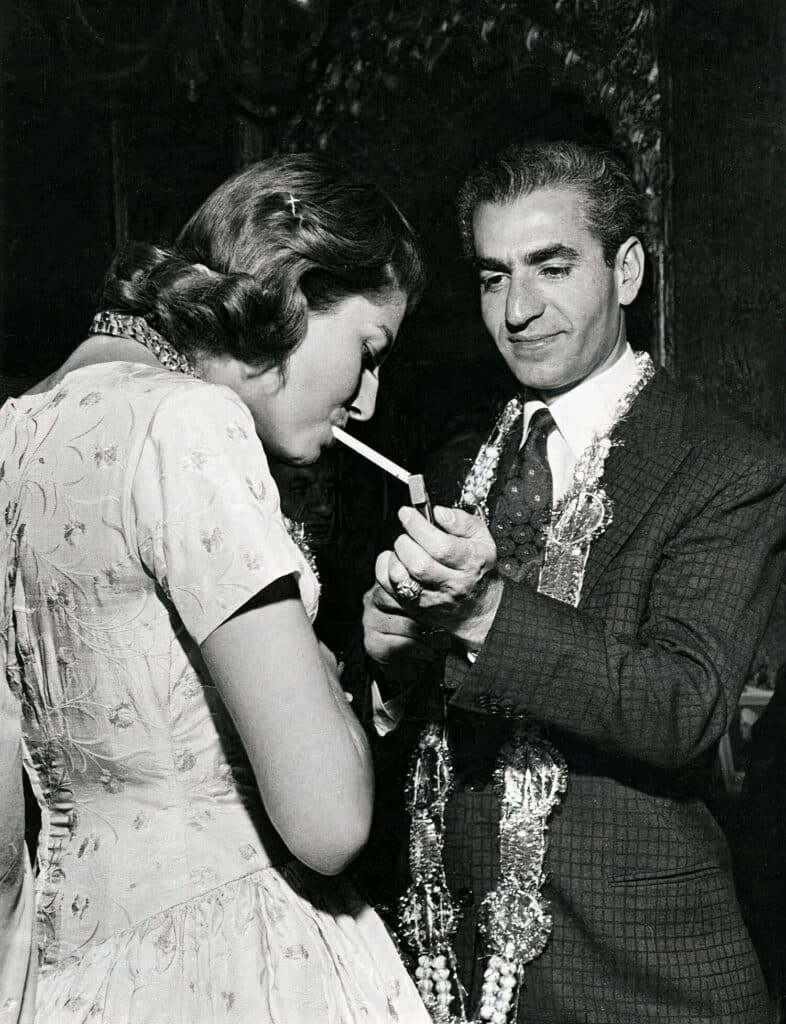

The Shah lighting a cigarette for his wife Soraya in the 1950s

This saw the Shah become an advocate for women’s rights and secularism. The Shah also began to emphasise Iran’s Persian heritage, as a state which was descended from Cyrus the Great’s Persian Empire, rather than the Islamic Shiite identity, which had dominated since the 1500s.

The Shah, fearing America would not protect Iran from a Soviet invasion, opened negotiations with the Soviets in the late 1950s for a non-aggression pact, but was pressured by the Americans to abandon this effort. This greatly soured relations with the Soviets.

In 1963, the Shah launched the White Revolution, a series of reforms which greatly undermined the Shia clergy and saw the clergy become fiercely opposed to his rule.

The Shah speaks about the principles of his White Revolution, 1963

This led to two assassination attempts by Islamists. The Soviets also attempted to kill the Shah in the 1960s.

The Shah’s reforms were largely successful and through the 1970s, the country saw economic growth similar to that of South Korea and Taiwan.

Resentments were however present. The Shah had made many enemies among the secular socialists, and the old Islamic clergy. The Shah had established the SAVAK secret police in 1957, and he used it to suppress opposition. His lack of democratic reform angered the left-leaning intellectuals and middle classes who saw democracy as the next step in Iran’s improving fortunes, and his anti-clerical reforms angered the clergy and their traditionalist supporters.

Several events would conspire to destabilise the Shah’s rule in the late 1970s.

An economic contraction hit the country in 1977 and 1978, and the Shah, who had been diagnosed with cancer in 1974, became distant and lethargic. He also became isolated from his American allies, whom he had supported by raising the oil price in the 1970s. President Jimmy Carter did not like the Shah and sought to cut military aid, in light of human rights abuses.

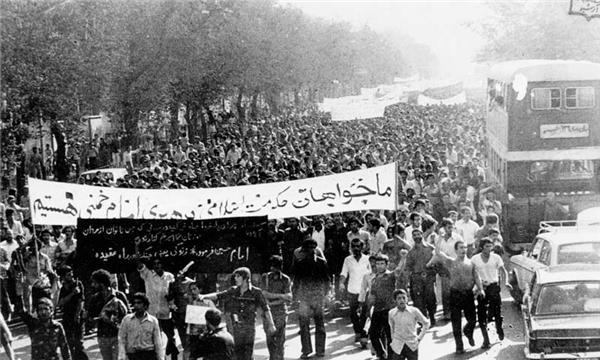

Demonstration of 8 September 1978. The placard reads: We want an Islamic government, led by Imam Khomeini

Protests against the Shah intensified in 1978 and sermons by an exiled cleric Ruhollah Khomeini calling for the destruction of the regime became popular with anti-government protesters. Suffering depression arising from his cancer treatment and crippled by indecisiveness, the Shah allowed the protests to grow into a crisis which threatened to overthrow the government.

Hi wife, angry at his indecisiveness, asked him to go abroad for cancer treatment and appoint her regent, promising that she would deal the with the crisis. He refused, but also did not act to end the crisis.

The Americans began to correspond with Ruhollah Khomeini as early as 1963, when he was in exile; he professed that he was a moderate, who liked the role the US played in the region as a counter to the Soviets and the British. The Americans believed he was a democratic reformer who would not interfere with their interests. As the Shah’s regime collapsed through 1978, the Americans intervened behind the scenes to prevent a military coup and invited Khomeini to return to Iran.

On 16 January 1979, facing major protests, the Shah fled the country, claiming he was seeking medical treatment, and the government collapsed. Khomeini returned to Iran, as the most popular figure in the anti-government forces.

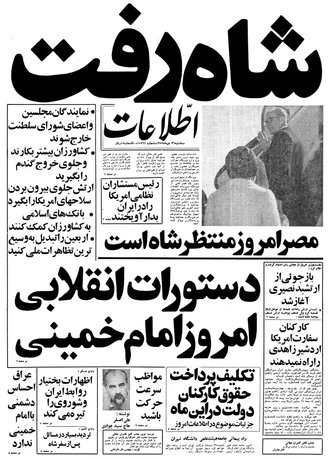

The Shah is Gone – headline of Iranian newspaper Ettela’at, 16 January 1979, when the last monarch of Iran left the country

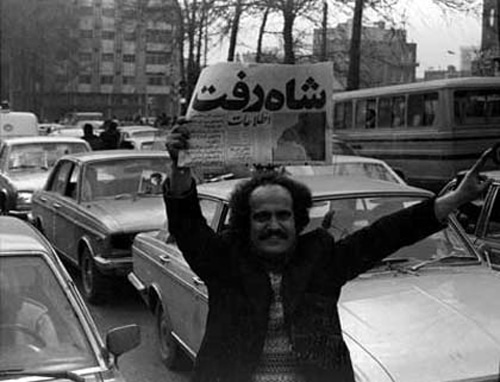

Ettela’at newspaper in the hand of a revolutionary when Mohammad Reza and his family left Iran on 16 January 1979: “The Shah is Gone”.

The Shah’s last prime minister Shapour Bakhtiar tried to form an interim government, but Khomeini appointed his own prime minister and declared allegiance to Bakhtiar as disobedience to God. The army soon defected to Khomeini’s side. Bakhtiar was forced from office on 11 February.

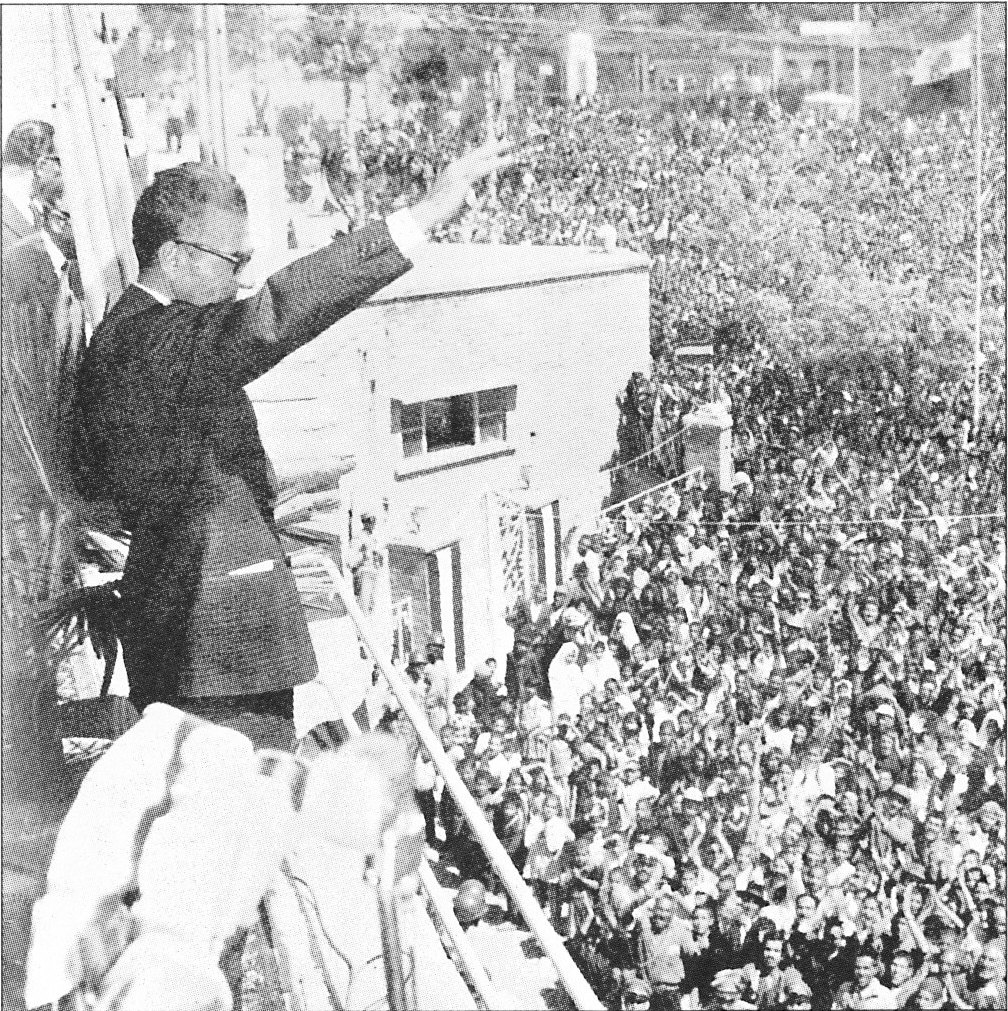

Khomeini’s return

During his exile, Khomeini courted the secular socialist opposition to the Shah and promised a democratic regime. However, after coming to power, he quickly turned on his former socialist and democratic allies, crushing them and establishing an Islamic Republic, with a revolutionary ideology with himself as the Supreme Leader.

A revolutionary firing squad in 1979

He became aggressively anti-American and established the motto of the new Iranian regime as Death to America and Death to Israel.

The Islamic regime in Iran has remained committed to their ideological goals of revitalising the Islamic world under clerical Islamic republics and has supported Shiite groups across the Middle East, from Iraq to Lebanon to Yemen.

The Shah died in Egypt 1980, and his eldest son, who continues to claim the title of Shah of Iran, works as an anti-Islamic Republic activist seeking to return the monarchy to Iran.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend