In his letter to the country last week, President Cyril Ramaphosa lauded the cooperation between business and the government. Their combined efforts, he wrote, were making a tangible impact on the numerous problems confronting South Africa, in electricity, in logistics, in security and so on. They would be partnering to address South Africa’s greylisting by the Financial Action Task Force.

‘We have long believed that it is only by working together that we can make progress. The partnership between government and business has shown what is possible when we are focused and committed towards the achievement of a common goal’, he concluded.

For a country with a sophisticated economy, an economy that necessarily must be outward-facing and that has aspirations to grow – in other words, maintaining and deepening its economic complexity – a cooperative relationship between business and the government is an important asset. For the government, business provides (or should provide) the engine for wealth and employment generation, and the platforms for innovation. For business, just about everything that the government does has a bearing on its operations: maintaining physical security, providing the satisfactory upkeep of infrastructure, ensuring standards of human development and so on.

A sophisticated business environment is not possible without effective governance, and it’s hard to see government enduring as more than a husk without an economy to underwrite the society over which it is presiding.

In the background of the President’s missive stands a long-standing preoccupation with ‘compacting’ or ‘social partnership’. This dates back to the industrial relations system established in the 1990s, the idea being that the government, business, labour and a strange conglomeration called ‘the community’ would get together and hammer out joint paths forward to the benefit of all.

Successful relationships

No less than any other relationship, a constructive relationship between business and government must proceed from a mutual realisation that they need each other. They may have severe disagreements, but each will need to recognise that the other brings to the table something that they need. In reality, this tends to be about the orientation of the government. Business cannot escape the reach of political power and state administration, so – maybe holding its nose – it will be inclined to try and reach a reasonable modus vivendi. Governments, on the other hand, wield a different type of power. It’s not uncommon for politicians to have scant understanding of business, especially as politics has become a professionalised, lifetime career. Ideology may feature strongly in politicians’ worldviews, inclining them to an instinctive hostility towards business.

And where lines of accountability exist for governments, they will often bend to distinct interests that may not be in line with those of the broader business community.

Indeed, it’s uncertain whether one can in fact talk of business as a unified whole. As South Africa’s own history attests, different sectors can have very different interests, different firms may have different priorities and may choose different strategies for engagement. Individual businesspeople may have political sympathies that push them to demand or accept terms that others baulk at.

Nevertheless, there have been examples of successful cooperation.

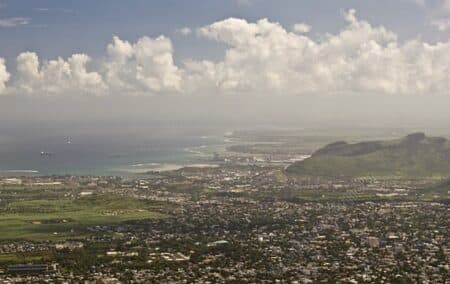

Mauritius

A particularly interesting case is that of Mauritius. Not unlike South Africa, Mauritius is a society with ethnic cleavages that have historically coincided with economic positions. Historically, its economy was founded on sugar plantations, and after independence, it was sugar exports to Europe that underwrote a modest degree of prosperity. At this time, a corporatist arrangement had seen the government, the major sugar producers and labour agreeing on economic targets. These relationships imprinted themselves on the island’s later arrangements.

However, the manifest vulnerability of depending on a single commodity led the Mauritius government to pursue a diversification strategy, with an emphasis on manufacturing, particularly on Export Processing Zones. Business was seen as a partner, and provided substantial equity for the new ventures.

Interestingly, the effective dominance of the government was recognised, but accepted by business, since the state was viewed as a generally competent institution. If it was dominated by people of Hindu Indian extraction, and if there were concerns about elements of ethnic preferment, this was seen as being less important to career prospects than competence and expertise.

Mauritian business had a long-established set of representative institutions – a Chamber movement dating from the 19th Century – which was able to articulate positions. This was, of course, not without its weaknesses, given the diversity of its business community. Indeed, as the economy diversified, the diversity of interests increased. But it provided a fairly coherent voice that could make a ‘business’ case to the government.

For its part, the government lent an attentive ear to what business had to say. This was despite the very different ethnic base of much of the business community: businesspeople, initially at least, often being of European or Chinese extraction. In a sense, the government was willing to pay attention despite the lack of an immediate political incentive to do so.

Generally, policies that were broadly acceptable to business were maintained, despite changes in government, and despite the ‘radical’ pedigree of some incumbents. What is worth noting is that on occasion, business took issue with particular policy stances, and was able to achieve important concessions – though certainly not all.

Antoinette Handley, a Canadian political scientist, commented about the country in a study of the relationships between its government and the business sector in Africa:

Mauritius enjoys both a relatively strong developmental state and a vibrant and autonomous business community. The country’s particular policy outcomes can be explained in large measure by the quality of its state. Although not free of corruption or personalistic politics, the Mauritian state is nonetheless much closer to the developmental state of Wade and Johnson [Robert Wade and Chalmers Johnson, two prominent scholars of the developmental state] than to any archetypal neo-patrimonial state. Unlike the governments of Ghana and Zambia, the Mauritian state had the demonstrated capacity to prioritize particular sub-sectors, design programs to develop these, and carefully listen to firms within those sub-sectors.

But the quality of the private sector too in Mauritius has been high. Historically held at arm’s length from the government, the business community was not able to rely on kickbacks from the government in order to survive. Rather, ethnicized hostility combined with the export orientation of the economy forced firms to look to their own competitiveness. Consequently, Mauritius developed a range of well institutionalized business associations, capable of taking a long-range view of the economy. All of this accounted for the ability of business and government to have constructive policy discussions when out of the public eye.

Mauritius continues to be a prospering, upper middle-income economy. If its economy no longer grows at the rates achieved in the 1980s, it maintained an entirely respectable 3%-4% growth rate over the past decade. World Bank data puts its GDP per capita at $10 256 in 2022; this was against South Africa’s $6 767 (current US dollars). In fact, in 2010, the countries’ respective GDP per capita were near identical, at a shade over $8 000 each. The changes that have occurred since speak volumes about the state of these two economies.

e.g. South Africa

South Africa built supposedly consensus-and-cooperation systems into its post-apartheid system. These included its National Economic Development and Labour Council (Nedlac), the sectoral bargaining councils, and Sectoral Education and Training Authorities, all of them institutions conceived to ensure common vision and industrial peace, and accelerate the attainment of social goals. None of this has been accomplished. As Dirk Willem te Velde of the UK Overseas Development Institutes drily wrote in a document studying the relationships between governments and business: ‘Formalised SBRs [State Business Relationships] can promote economic performance, e.g. through improved allocative efficiency of government spending and better growth and industrial policies (e.g. Mauritius). Yet, SBRs need to be disciplined by a set of competition principles, or they risk becoming collusive rather than collaborative. Not all formal SBRs work well (e.g. South Africa), and informal SBRs can play a key role (e.g. Egypt).’

So, if Mauritius can be described as representing the ideal that South Africa strove for, why is it that things have turned out so very differently?

In general terms, the context was different. Whereas Mauritius – ethnic division and all – has long been a ‘normal’ functioning democracy, South Africa transitioned to democracy from a traumatic past under the leadership of a political organisation that viewed itself as embodying a messianic mission. From this followed a very different framing of objectives. For Mauritius, it was about accelerating growth, and building on opportunities in view of its inherent vulnerabilities. For South Africa, the ANC had in mind the total transformation of society. The relationship between business and the government in Mauritius was fundamentally about economic matters, while that in South Africa was substantively refracted through political considerations.

South Africa’s approach would make it extremely difficult to identify priorities, or even to know when goals had been achieved – if indeed they ever could be, since the ANC’s intention was invariably to ratchet up demands until that ‘total transformation’ had taken place. The escalating demands in empowerment charters or in employment equity legislation illustrate this.

Flowing from this situation was the question of trust. Again, as in any relationship, it’s necessary to accept that one’s interlocutor is acting in good faith. The ANC never felt this way about business, viewing it as complicit in apartheid, putting ‘profits before people’ and being unwilling to ‘transform’. This was helped along by a strong current of Marxism within its intellectual bloodstream. And paradoxically, it was aggravated by the growth of an ANC-aligned business lobby – sometimes directly dependent on party patronage – which intended to capitalise on its political influence.

Business had its own concerns about the capacity of the ANC to manage the country, but typically concluded that discretion was the better part of valour (at least until the end stretch of President Mbeki’s tenure). It went along with the latter’s plans, trying to alleviate some of the worst consequences. When businesspeople did speak up – as Tony Trahar, then CEO of Anglo-American did on the issue of residual political risk – they could be fearsomely put in their place.

Another problem that has bedeviled the relationship is that the business ‘voice’ has been fragmented and (sometimes) contradictory. While there were early efforts to create bodies that encompassed various shades of business – particularly to bring so-called ‘black business’ and its interests into the agreements – these have not been entirely durable. The split of black representatives from Business Unity South Africa in 2012 to form the Black Business Council was a major such instance. The government of the time seemed to tacitly endorse this decision, sending ministers to its events, and inviting members onto government delegations abroad. Then president Zuma was actually quoted by one of the BBC’s leading lights as having adapted Steve Biko saying that ‘black man you are on your own with your government.’

The tenor of those words, and policy prescriptions such as the black industrialists programme, point to another feature that complicates and undermines productive relations. This is collusion. Think of this as a distorted version of a relationship between business and government, one in which rather than working together to promote broadly desirable common objectives, they promote narrow sectarian interests. Collusion invariably functions to apportion benefits to particular firms, with costs – in terms of inflated prices, uncompetitive markets and reduced incentives for innovation – passed on to society as a whole. This works squarely against the imperatives of a complex economy.

In some ways, this has now become a feature of the economy. Donald Mackay of XA Global Trade Advisors recently said on a podcast with Peter Bruce that South Africa’s attempt to use protectionist measures to foster domestic industrial growth was perversely creating a class of business that was effectively unable to function without that support. ‘Support’ measures for firms were even being introduced that demanded things like local procurement from firms yet to be established.

To this one might add that the ANC, having recommitted itself to prescribed assets, assured South Africa that the funds so commandeered would not only be directed to Eskom and Transnet, but also to private sector projects that advanced South Africa’s industrialisation agenda. The moral hazard and the prospects for collusion (if not the inevitability of collusion) are frightening.

Perhaps most unfortunately, South Africa’s government is showing very little ability to manage its basic functions, much less pilot the ambitious tasks of its imagination. South Africa has a government that must be engaged with, but a spotty record of actual governance to cooperate with.

The sentiments recently expressed by Minerals and Energy Minister Gwede Mantashe were especially revealing. Business, he told the African Energy Indaba, should ‘stop crying’ and cooperate with the government. This is a view often heard from government representatives. The problem is that ‘cooperation’ or ‘working with us’ comes with the implied rider of ‘on our terms’. Assisting in keeping the lights on or to fill potholes in the country’s cities (or – darkly amusingly – to provide wardens to direct traffic at intersections) is acceptable; accepting advice about reforming the systems and choices that have led to this dire state of affairs is not.

Think of the recent National Health Insurance Bill, and the cavalier disregarding of business’s input. This despite the implications, direct and indirect, of this measure – and the fact that it still remains to be seen how the NHI is to be paid for.

All of this puts the president’s comments in a proper light. South Africa is in utter crisis following decades of ideological, dirigiste governance, Louis-Vuitton-meets-Che-Guevara-revolutionising and general suspicion of business. The scale of the crisis has forced the government to open the door to help from business, against its instincts. Business is stepping up in no small measure because the state of governance is a dire threat to itself. But this signifies very little importance about the nature of the relationship.

Looking forward

South Africa would benefit greatly from a cooperative relationship between business and the government, although the prospects for this are at present bleak. There is too great a cloud of mistrust over their interactions, some historical, some current, and the government has proven itself in recent years a poor partner for cooperation.

Nevertheless, such a relationship is necessary for South Africa’s survival, for a sophisticated economy, and for its prospects of future growth. Whether it is the project of a reformed ANC (an admittedly implausible notion at present) or a reformist successor government, this relationship will need to be addressed.

Relationships of mutual dependence rely on each party understanding its own interests and the limits of what it can achieve and what it can demand of its counterpart. Neither has the capacity to fulfil the other’s role, and neither should they seek to. Rather, there must be an acknowledgment of the distinct roles they play, and what each hopes to get out of the relationship. This would create the foundations for productive debate, which would necessarily be purely transactional at first.

Relationships are nurtured, not decreed. Each would need to dispense with any residual naivety about cooperation, and the difficulties inherent in actualising it.

Foremost here is to build a measure of trust. The ANC has never had much trust in business – for historical and ideological reasons – while it has done little in the past decade to demonstrate trustworthiness. On some level, business would need to feel assured that its contributions are valued and seriously reflected upon. Importantly, the government needs to cultivate its own expertise, genuinely capacitated and well-informed civil servants who understand the economic environment and the workings of business. Trust will follow excellence.

This is not to make a case for unfettered sympathy on the part of government for business’s positions, but to create an environment within which productive, even tough, debate can be undertaken. And to form an internal reality check for government on some of its more fanciful ideas.

This also raises the thorny issue of what constitutes ‘business’, and what mandates representative organisations should carry. This, it must be conceded, is a difficult one. What is of concern – and within the capacity of the organisation to address – varies vastly between a major bank and a small jewellery manufacturer. Indeed, this disjuncture has been one of South Africa’s signal problems – the ‘cooperating’ institutions that exist are heavily skewed towards larger interests, both in business and labour. Sectoral determinations, for example, reflect this conjuncture, to the exclusion of small business (though the latter have been punted since PW Botha’s time as the ever-great hope for economic redemption…).

One solution is a mass exemption from such determination of all firms below a particular level or employment or turnover – or perhaps abolishing the system altogether, though this would probably not be politically saleable.

Along with this, efforts need to be made to resuscitate the Chamber movement: those small, local Chambers of Commerce representing businesses in towns and dorps across the country. These used to exist with some influence, but have gone into something of a decline in recent years. This is the level at which smaller firms could make their demands and concerns known, and at which some of the key challenges to their viability manifest themselves. That being said, South Africa’s municipalities often represent the country’s pathologies on a small, more intense scale. Municipal governments are perhaps frequently less able to interact with business than their national counterparts. This too would need to be addressed.

What this means in sum is that putting the relationship between business and the government on a sound footing is foremost a matter of shifting mindsets. Cooperation requires give-and-take, and being willing to acknowledge the inadvisability, if not the impossibility, of some of what may be deeply desired. President Ramaphosa’s government has not realised this, and South Africa is paying a steep price in lost growth and compromised economic complexity as a result.

[Photo: flickr]

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend.