If you pay attention to what is happening, you can learn some basic principles of economics. This makes sense, when you realise that economics is about a theory of human action. What motivates people? How do they choose between competing choices?

These are all questions answered by simple observation.

At my age, I need to take time off from being on my feet, so I watch some television to pass the time. One show I watch is Antiques Roadshow — both the American version and the BBC version.

I assure you, none of the appraisers are out to teach basic economics, but they do whether they are aware of it or not. Often the person anxiously seeking a nice appraisal does the same, but is equally unaware of it.

Supply and demand

One primary lesson that they teach is that prices are determined by the interaction of supply and demand.

Frequently someone will bring on a piece of old Chinese porcelain that granddad bought 50 years ago, or that they found in a yard sale for some miniscule sum. Now one thing about the reruns of these shows is that you can see shows from 15 years ago and episodes from last year.

The demand for such art objects used to be rather limited. China liberalised some of its economic policies while remaining a vicious dictatorship. But freeing up markets did increase economic productivity, and some people became rather wealthy. They started seeking out antiques for their own homes or collections.

An older episode I saw had the appraiser giving his estimate on value, but openly saying that anything goes now, because demand for these historical art pieces in China is exploding. Supplies don’t increase easily. Fakes started to come out of China, but demand was going up by the day.

In other words, as the supply of a good remains constant or falls, but demand increases, then prices, or the value of the item, will go up. With more Chinese money seeking antique art, prices had to go up. Even the many who have successfully fled China for free countries still cherish their cultural history.

The same episode can have an appraiser informing a guest on the show that their object was once popular in the wider culture, and prices a few years ago were quite high, but in recent years its popularity waned, and values plummeted.

Value

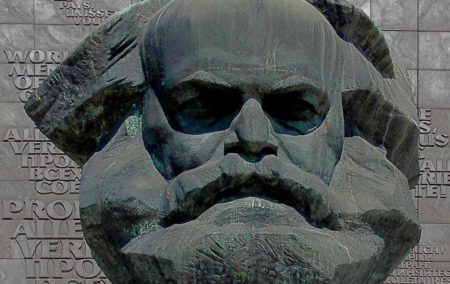

All this skirts around the economic problem of value. What gives a product value? Once that is figured out, one of the most popular theories of value — and economic policies built on it — falls by the wayside. That would be the Labour Theory of Value, which is popularly associated with Karl Marx, but was widely held for decades before he came along. In fact, even Adam Smith fell for that theory.

But look at how something as simple as evaluating the worth of antiques on a TV show disproves it. The value of the goods being appraised can rise or fall with the demand from consumers, even though the amount of labour invested in a product doesn’t increase as its value does.

The labour used to build a cabinet in 1775 remains constant. It is a spent investment that remains the same regardless of the market value of that cabinet today. There are plenty of items that took very little labour to make 50 years ago and that are worth a pretty penny now. There are also objects that took a lot of labour to build that have very little value today.

You wouldn’t think a piece of Chinese porcelain was all that was needed to disprove the economic theories of Marx, but it does. As with all items. If you find a 10-gram gold nugget lying on the ground, its value is the same as a 10-gram nugget that was dug out of the earth with hard labour.

Subjective

That reveals one of the main points of modern economics: The Subjective Theory of Value.

An item has value for one reason only — people want the good or service. What they don’t want has very little value, no matter how much it cost to produce. The father of the subjective theory was the economist Carl Menger who noted: “What one person disdains or values lightly is appreciated by another, and what one person abandons is often picked up by another.”

His student, Ludwig von Mises , put it this way: “Value is not intrinsic; it is not in things. It is within us.” It’s as if economics is repeating the mantra of love heard often in popular culture: What the heart wants, the heart wants. It has value because people value it, not because of the labour put into it and not because of the resources needed to produce it. Its value is entirely subjective.

That alone undermines a major principle on which Marxist economics is based.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend