The 2024 election results will be chaotic. With no party in a majority, President Cyril Ramaphosa will probably call for a government of national unity (GNU). The markets and foreign diplomats will welcome this. Ramaphosa will even regain some of his lost political capital and rise again as Mandela’s chosen heir. And the DA will be trapped in an impossible position: it can work with the ANC and lose all credibility, or refuse to work with the ANC and receive the blame for national failure or intransigent obstinacy.

However, with enough strategic forethought over the next few weeks, the DA can avoid catastrophe.

The purpose of an opposition party is, simply, to earn political capital. Political capital is the difference between relevance and irrelevance, between a future and failure. No opposition party can change the arithmetic of election results – and the DA shouldn’t consider this to be their job. Simply put, it’s not the DA’s job to rescue South Africa from its voters. While it is conscious of and building on its liberal heritage, it’s the DA’s job to secure successive political wins that will result in electoral endorsement into government.

And to win in politics, there’s only one way: maximise your ability to earn more political capital than your opponents.

To explore the DA’s most viable route to earning more political capital than its opponents, this is what the party, the inheritor of the political liberal, non-racial, and pro-free markets legacy of South African parties over a century, must do.

How effective

Starting immediately, the DA must take stock of how effective it has been as a party of opposition – and build on this. It is dangerous short-termism that stakes the success of a 20% party’s election campaign on the overturning of a three-decade majority. The DA’s ambition of ousting the ANC from government is laudable and worthwhile, but it cannot become the success measure of the DA’s 2024 campaign, if the party wishes to maintain any momentum in its efforts to earn more political capital in 2026 and 2029.

Removing the ANC from government is, in the minds of South Africans, a one-time act. Once done, what remains to be done? If the DA’s objective for the next five years can be achieved on election day, or in the months after the election, what drives the DA’s earning of political capital for the next five years? If the ANC is removed from power – and the Multi-Party Charter (MPC) is without a majority, as is almost certain – what mandate has the DA received from its voters? What message can it share with South Africans from that point, other than a report-back on its failure to replace the ANC with a viable alternative? Getting the ANC below 50% would be no mean or unimpressive feat, but with no coherent alternative majority, the DA will face the horror scenario of post-2021 Johannesburg on a national scale: a country in a terrible and deteriorating state, a barely functional economy, a captured civil service, a fiscal disaster zone, and no path to anything resembling a feasible governing majority for a non-ANC government.

Bear in mind, this would be following an election where the DA would have got its biggest-ever share of the vote – an accomplishment unimaginable from the perspective of 1994 when the DP scraped into Parliament, or 2004 when the DA was collapsing under its founding contradictions, or 2019 when the party’s vote share declined for the first time.

On the back of a remarkable and far-from-guaranteed recovery, the DA would have set itself up for a loss. Instead of the most successful opposition party in our country’s history, the DA, if its campaign mission over the next two months remains defined as leading into power a post-ANC government, will exit the 2024 election campaign a failed party of government. The narrative will be ‘DA fails to lead chaotic opposition into government’ where it should be ‘ANC falls below 50%, DA back on growth track’.

Taking stock of its impressive record as an opposition party – a track record even ActionSA heavyweights like Sello Lediga has lauded for its tenacity and power in preventing more extensive ANC destruction – the DA must realise that the real choice facing it in a post-2024, post-ANC majority political landscape is whether the party wants to be the most formidable opposition in a century, able to earn political capital and grow, either in size or confidence, for 2026, 2029, and beyond, or be part of the most stumbling, fumbling government in South African history.

For that is what a Ramaphosa-led GNU will be: an incoherent coterie of the corrupt, the cadres, the crooks, the cronies, and the useful idiots.

Shortsighted

Some have argued that the DA could, within such a government, carve out one or two ministerial portfolios that could become islands of excellence, and become a new way for the DA to earn credibility in government. This is, again, dangerously shortsighted.

South Africans, whilst by no means politically stupid, are not politically sophisticated. In a country where Maslow would have a heart attack for the discombobulating levels of his hierarchy both manifesting and not manifesting, it is hardly surprising that citizens are broadly disconnected from politics – and likely to remain that way. This is not a political setting that will allow for nuanced carve-outs of this or that cabinet position.

In a country where the constitutional spheres of government barely register as salient, how could people be expected to keep count of which portfolio belongs to which party and which success or failure is due to the work of which minister? The DA should have learnt from its leading of a successful Cape Town coalition from 2006 to 2011. The credit earned by a coalition government is never truly shared by the leading party with the others – not, at least, in the voter’s perception. Another example is the Liberal Democrats in the UK who limped out of the 2010-2015 coalition and still have not recovered a decade later.

But, just as the political realities of full membership of a GNU are cruelly inescapable, the DA cannot risk the opposite: being perceived to sit idly by, tutting at voters for not voting for them whilst our country sinks to new lows. This, too, would be the strategy of a political party with a death wish and an opposition party incapable of understanding that its key reason for existence as an opposition party is to maximise its ability to earn political capital.

Were the DA to go with a ‘not my job, not my problem’ approach in obstinate opposition to a Ramaphosa-led GNU, 2026 and 2029 will see the party suffer its own voters’ wrath – voters who expect the party they vote for to do more than wait in the opposition benches for a majority.

Having taken stock of its success as an opposition party, the DA must urgently start redefining what a win for it in the 2024 election will look like. It is welcome, and probably obligated, to maintain that deposing the ANC remains part of the mission, but the DA must start telling the electorate that a humbled, sub-50% ANC and an ascendant DA leading a reinvigorated parliamentary opposition can be considered a victory worth achieving.

Pitfall

Redefining victory in this sense avoids the pitfall of perceived DA failure, should a national MPC government fail to materialise. Instead, the DA creates a win-win for itself and, if communicated to the people, also for South Africa. If the MPC breaches the unlikely 50% mark, the DA leads the country into a post-ANC future; if the MPC falls short, an re-empowered, reinvigorated, mission-focused DA stands ready to fight where needed and to support, where appropriate, a humbled Ramaphosa-led ANC in government.

However, for this to be realised, the DA must urgently out-think Ramaphosa’s ANC – a political movement capable of fighting vigorously for its own survival. Ramaphosa’s call for a new GNU, for a CODESA III, will come within hours of any result indicating a hung Parliament. The DA must anticipate this and pre-empt it with a unity message of its own, but one that will widen rather than lessen their strategic scope.

John Steenhuisen must within the next few weeks deliver a speech, with markets and foreign diplomats listening, stating that, whilst it may not be time for a GNU, it might be time for a politics of national unity – a constitutional state of national unity.

“And in this constitutional state of national unity,” Steenhuisen must say, “my party, the DA, will play our part. If the South African people vote that no party or coalition in Parliament has a majority, the DA will step up to serve. But the people of our country are not simply served from the Union Buildings – our constitutional democracy is about more than who gets to sit in the back seats of ministerial cars. As such, the DA will serve our country in the best way we can, should the people on 29 May choose a constitutional state of national unity. The DA will do this by supporting the election in Parliament of a GNU as long as the sacred principle of accountable government is protected.

“Let me say this now, before the election so that the people of South Africa can make the final and democratic decision on this: if a GNU is the will of the people of South Africa, the DA will not obfuscate or trade horses for ministerial mansions. But we will step up and we will not give up on government accountability. And I do not think for a moment South Africans expect us to.

“As much as I want to lead my party into the Union Buildings, I will not let my ambition stand in the way of a true constitutional state of national unity. To show the DA’s good faith on this, the DA will support a GNU as long as we as a party can play, as we have done proudly, our part in holding a new government to account in a newly empowered Parliament.

“Without beating about the bush, this means the election of a DA Speaker of Parliament and the election of DA MPs to nine parliamentary committee chairs most vital to accountability through the rooting out of corruption and the oversight of policy.

“I am proud to today announce ten nominations as the foundation of the DA’s good-faith contribution to a new era of collaborative politics that puts unity of success and dedication to accountability first – as all South Africans desire.

“I propose, in the national interest, the election of Bridget Masango as Speaker of Parliament for the 2024-2029 democratic term.

“For chair of the Parliamentary committee on Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs, I propose the election of Ashor Sarupen.

“For chair of the Parliamentary committee on Employment and Labour, I propose the election of Kabelo Kgobisa-Ngcaba.

“For chair of the Parliamentary committee on Finance, I propose the election of Dion George.

“For chair of the Parliamentary committee on Health, I propose the election of Michéle Clarke.

“For chair of the Parliamentary committee on International Relations, I propose the election of Siviwe Gwarube.

“For chair of the Parliamentary committee on Justice and Correctional Services, I propose the election of Glynnis Breytenbach.

“For chair of the Parliamentary committee on Mineral Resources and Energy, I propose the election of James Lorimer.

“For chair of the Parliamentary committee on Police, I propose the election of Ian Cameron.

“And for chair of the Parliamentary committee on Transport, I propose the election of Thamsanqa Mabhena.”

Steenhuisen must make clear in this speech that this list of nominations by no means replaces or contravenes the DA’s commitment to the MPC. He must also announce that he will remain in his position “if the voters of South Africa choose”. With this team of parliamentary change leaders, a team to mobilise across the country, the DA should enter the final weeks of the election campaign with a straightforward message to voters: “Whatever you decide, a new government or a new era of accountability, the DA is ready to deliver.”

With this message established, the DA must ready itself for an election result along the following lines:

ANC 40%

DA 25%

EFF 10%

MK 9%

IFP 3%

FF+ 2%

ASA 2%

ACDP 1%

PA 1%

Others 7%

Results

Once all the results are in, Ramaphosa is likely to address the nation and set out that it is his presidential and patriotic duty to now call for the political parties of South Africa to “do more, together” through a GNU – even another CODESA. And, able to claim an endorsement of its proposition of a reinvigorated accountability in an era of complex multi-party, GNU-type governance, the DA will be able to maintain the moral high ground of a reasonable, moderate, and good faith offer in the national interest. Ready for Ramaphosa’s play, the DA will be able to move swiftly into a position of advantage amidst political chaos.

Where full collaboration and coalition with a Ramaphosa-led GNU would taint the DA as sellouts, and unqualified refusal to meet such a GNU somewhere in the middle would scar the DA as self-interested game players, the ‘constitutional state of national unity’ will minimise any fallout damage, allow the party to exit the campaign with a win, and, crucially, set the party up to play to its strengths as an opposition party into the 2026 and 2029 election cycles.

A result along the lines of the numbers above will likely bring an end to the MPC, in any case.

The IFP has increasingly become politically vulnerable over the last few months – in no small measure due to the rapid and aggressive rise of Jacob Zuma’s MK. As such, it’s important to distil the reason for the IFP’s existence. And, despite a history of half a century, this distillation is simple: the IFP has only ever had one fundamental and consistent objective – governance of the geographical Zulu homeland.

An ANC on 40% nationally is an ANC that has fallen below 30% in KZN. If recent opinion polling and by-election results are indicative of the true state of play in the province, the ANC, IFP, and MK are in a statistical tie around 25%. From the ANC’s perspective, the calculation is simple: if the party wants to keep control of the province, it must work with the IFP. For the ANC, a coalition with the IFP would not only be familiar, harking back to the 1994-2009 era of the two parties in power in KZN, but also safer. MK is an unpredictable party – one possibly on the rise. It would therefore be difficult for the ANC to maintain any sort of upper hand in an ANC-MK coalition. The IFP, on the other hand, is a party of significantly less potency and agility – a much likelier supplicant coalition partner.

Power sharing

With the stakes at play both nationally and provincially, the ANC would be able to entice the IFP with power sharing, perhaps being as generous as proposing an IFP premier in KZN or, more pragmatically, a rotating premiership-deputy premiership arrangement of an Israeli type. In exchange for allowing the IFP to achieve, for a term at least, to stop the bleeding, its cherished political objective in some shape or form, the ANC would receive approximately 12 crucial seats in the National Assembly. An ANC-IFP coalition in the Assembly would occupy 172 seats – only 29 short of the 201 needed. Given this mutual benefit of ANC-IFP collaboration, it is easy to see the IFP endorsing Ramaphosa’s call for a GNU, bringing an end to the MPC effort.

With the MPC disintegrating, the ACDP is the next party likely to heed Ramaphosa’s call for unity. Ramaphosa’s history as a struggle-era leader of the Student Christian Movement, after all, comes into play here – an opportunity to win Kenneth Meshoe over. This will test the ACDP’s commitment to its broadly free-market economic policies. In exchange, Ramaphosa could promise a referendum on abortion and a government committed to conservative social values.

It will be a potent offer, and while Meshoe might resist a full agreement for the ACDP to join the ANC-IFP GNU, his party will see the appeal of a confidence-and-supply arrangement whereby the ACDP, with its roughly four seats, plays a role in electing the government from the National Assembly, but remains on the opposition benches. With the ACDP aligned to his cause, Ramaphosa’s GNU will be only 25 seats short of securing the presidency.

Rise Mzansi will, like the DA, though to a significantly smaller extent, be in an awkward position. Despite the party’s policies on BEE, empowerment, and, to some extent, property rights, Songezo Zibi would spike his party’s political capital out of the gate, were they to seem too eager to keep the ANC in power. That said, the party is a likely candidate for joining Ramaphosa’s GNU – or at the least, supplying a few further votes towards Ramaphosa’s re-election. Despite Rise Mzansi’s bold claims of winning up to 7% of votes on 29 May, a total closer to 1-2% is more realistic. Consequently, Rise Mzansi’s 6 votes would likely be added to bring the votes in the National Assembly for Ramaphosa’s re-election to 182 – 19 short of a Ramaphosa victory.

Despite MK being little more than a turbocharged external ANC faction, it is difficult to see the party endorsing a Ramaphosa-led GNU. Zuma’s party might play hardball, stating a willingness to support an ANC-led GNU, but on the condition that it is not led by Ramaphosa. This will be a bridge too far for the ANC – not only is Ramaphosa one of the party’s strongest electoral and reputational assets, there is also no heir apparent ready to step in as a consensus leader in Ramaphosa’s stead. As such, Ramaphosa’s team will be foolish to expect MK support in the presidential ballot. There might be some chance of the secrecy of the ballot allowing one or two of the roughly 36 MK votes to trickle to Ramaphosa, but Zuma’s forces will likely keep their powder dry.

Smaller parties

Whilst it’s difficult to gauge the current standing of smaller parties like the UDM, GOOD, NFP, PAC, and ATM, these parties are, as per previous elections, likely to receive around 9 seats as a collective – all of them having MPs with much more to gain from a Ramaphosa presidency leading an ANC-IFP GNU coalition than any alternative government. If these parties join Ramaphosa’s GNU, it gets the number of votes for another Ramaphosa term to 191. To this total, one should add 2 Al Jamah-ah seats. The ANC has, through its policy on the Gaza conflict, secured this source of numerical support.

On a total then of 193 votes, 8 short of victory, attention must turn to the remaining members of the MPC, the FF+ and ASA, and the EFF. On the current scenario, Pieter Groenewald and Herman Mashaba lead caucuses of 8 MPs each, Julius Malema 40.

We can with some confidence discount the possibility of either the FF+ or ActionSA voting an ANC president into office. And whilst an EFF endorsement will comfortably put Ramaphosa over the top, the ANC will be cautious on having the EFF on board. Malema’s recent statement that the EFF will support the ANC on the condition of Floyd Shivambu becoming Minister of Finance is deliberately absurd – intended to price the EFF out of the ANC’s market.

Ramaphosa and at least incumbent Minister of Finance, Enoch Godongwana, both know that the ANC must capitalise on the positive market sentiment around a Ramaphosa-led GNU. The South African economy and fiscal situation require this as a baseline for post-election governmental operations scope. And a Ramaphosa-led GNU sounds significantly better and more responsible, stable, and moderate than an ANC-EFF-et al alliance.

But ultimately, whether the EFF joins the GNU or offers, as in 2016, a confidence and supply arrangement, or even votes for another presidential nominee from the National Assembly floor, the EFF could either secure Ramaphosa the presidency on the first ballot or deny him a victory in only the first few rounds of voting. However the numbers end up, a few up or down here and there, Ramaphosa’s mission to get to 201 votes in the National Assembly remains the same, given the anticipation of the final percentage results. A first-round victory for Ramaphosa is only sure if no other nominee is put forward in the National Assembly – an outcome that would help all players keep their cards close. If this happens, the numbers question of Ramaphosa’s GNU will only be answered later to gauge its stability. Whether Ramaphosa’s numbers challenge presents dramatically through competitive presidential ballots, or gradually following an uncontested Ramaphosa re-election, the DA’s strategic offer of stability on its terms should remain the same. Steenhuisen must ensure that party discipline holds.

The DA will have to call the play announced by Steenhuisen before the election: it will support the re-election of Ramaphosa in exchange for ten key parliamentary accountability and oversight positions. The DA must ensure markets and diplomatic actors understand that this is not a spurning of Ramaphosa’s unity vision – instead, it is a good-faith compromise that will deliver post-election stability.

Tempted

The ANC would be very tempted to accept Steenhuisen’s terms in exchange for something resembling a working parliamentary majority for a Ramaphosa-led GNU. Ramaphosa, as his biographers find, is a true believer in consensus. He is a struggle leader with little appetite for high-intensity conflict and surprisingly inept at managing it. And this is exactly the type of conflict that would be a daily challenge to him, were he not to establish a reliable majority for his swan-song presidential term.

In such an arrangement, Ramaphosa would find some scope for a rerun of his glory days as the smiling face of negotiations whilst receiving plaudits for leading his country and party through a turbulent election. At the same time, the ideologues in his party will maintain more of a hope for the NDR to be resuscitated than for the ANC to join forces with the EFF or MK to govern. The final component of the ANC, the opportunists and kleptocrats, will try a final round of rent-seeking before the expected implosion of the ANC in 2029. In a constitutional state of national unity, many conflicting interests find some solace.

With Ramaphosa elected and the MPC shattered, the DA must capitalise on its role as the most muscular opposition in South African history. Where the party has managed to hold the government to account through the courts against a mostly hostile Parliament, the new constitutional state of national unity will afford the DA unprecedented powers to earn political capital. A DA Speaker will have the opportunity to lead the rebuilding of Parliament. Committees will allow for an A-team of parliamentarians to deliver quotable, shareable, viral content to proliferate and earn political capital – think Glynnis Breytenbach’s massacre of the G4S executives ̶ but on a regular basis.

Where the DA before 2024 had intangible shadow ministries, a post-2024 DA in terms of a constitutional state of national unity must mobilise its newly boosted oppositional resources. One of the consequences of single-party domination in South Africa over the last century is that markets and foreign diplomats, key connections to influence and political capital earning investments, are unused to getting to know parties outside of government.

The DA is not known in global corridors of power – and, therefore, not highly rated. Utilising parliamentary chairmanships as something like parliamentary ministers offers a route out of this anonymity. In systems like that of the US and the UK, congressional and parliamentary offices are of significant importance and a DA understanding this, whilst maintaining its potent oppositional role in South Africa, can use the 2024-2029 democratic term to establish itself as a natural successor to the ANC.

This is the way for the DA to find a win in the near-unwinnable election of 2024, and to grow its political capital into 2026 and 2029. The shortest route isn’t always the fastest one – and the DA must realise this in time to avoid setting itself up for a lose-lose fallout on 30 May. This is the parliamentary strategy the DA needs to get beyond 29 May.

And it is the first third of what the inheritor of South Africa’s liberal tradition needs to do for a post-ANC South Africa.

The other two thirds are, perhaps, topics for another day.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend.

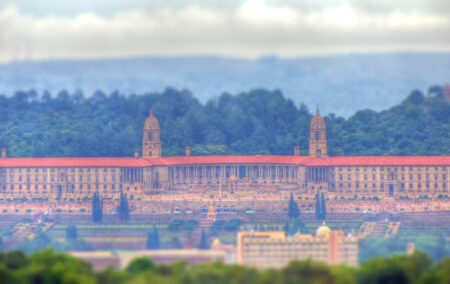

Image: Jcgill1000, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons