Recently, while waiting to watch a basketball game on satellite television in the godless hours of the morning I stumbled on a reality TV program called Listing Cape Town. The show was replete with jaw-dropping, nay, extortionate real estate prices fuelled by international money and wealthy Jo’burgers fleeing the diseased administration of that crumbling city.

Some readers of this article may even find my use of the word extortionate jarring but considering the dislocation between property prices and local incomes I would say it is appropriate and mirrors the dislocation in alpha cities all over the world like New York, Hong Kong, Singapore, Vancouver, London, and San Francisco. This dislocation has also come with social problems like a lack of affordable housing which is connected to drastic spikes in homelessness and vagrancy and to young people holding off on marriage and children and precipitous drops in birth rates.

These social issues have led to homeless encampments and sharp rises in drug use in states like California where housing policies favour luxury (expensive) developments and favour existing homeowners (largely boomers) over those who want to climb the ladder (Millennials and Gen Z).

The drop in birth rates all over the wealthy world while not entirely the fault of extortionate housing markets is causing all sorts of headaches for political leaders who worry about the future collapse of pension systems and tax revenues to maintain the comforts of Western civilization in particular without replacing their existing population (2.2 children per woman).

Sustainable

All this is to say that for Cape Town to become a sustainable juggernaut well into the future, some serious consideration needs to be given to (affordable) housing supply for middle-income earners. Thought must also be given to how housing policy must favour ordinary Capetonians and their aspirations to get onto the housing ladder and form vibrant families over luxury real estate agents and rich Europeans who are absent six months of the year.

Yes, I went there because I am unashamedly pro-ordinary Capetonians over any special interest groups no matter how moneyed they are.

It is here that the City of Cape Town can learn lessons from the City of Minneapolis which is one of the only major cities around the world (it has 16 Fortune 500 companies headquartered there) that has bucked the trends of low homeownership among young people.

Jeremy Gold, writing in the Brown Political Review, outlines how the city stabilised rent prices and avoided the housing-affordability crisis engulfing the major cities in the rest of America:

“Thanks to a sweeping set of 100 policies implemented at the start of 2020 known as the ‘Minneapolis 2040 Plan’, rent prices in the city have stabilized in the face of population growth and inflation—and despite higher housing prices throughout the rest of the state.”

Gold argues the biggest impacts were made by eliminating single-family zoning within city limits, establishing density minimums near public transit stations with higher standards near popular transit hubs, and incentives for and investments in affordable housing, both public and private.

While it is necessary to do some throat clearing and say that these things are most certainly on the radar of the City of Cape Town, they must take on increasing importance as more people flee to the Western Cape from diseased city administrations.

Sandwiched

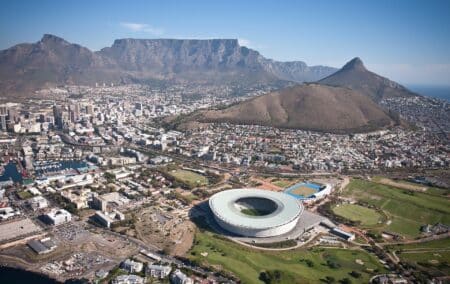

Cape Town is sandwiched between a mountain range and the sea and so the scope of sprawl is limited (thank goodness) and so density, especially near transit hubs, takes on greater importance, especially with the DA’s stated goals of “devolving the trains”. Integrating public transport (the trains) and affordable housing will also have the benefit of easing traffic congestion especially with all the new people moving in. It will also improve labour market efficiency, as people will be able to get to work faster and low- to middle-income people will be able to access the right jobs that fit their skills more often as they can cast their net wider. The underrated effect of that on prosperity in the city cannot be stated enough.

Perhaps more controversially, banning single family zoning within inner city neighbourhoods – provisionally I would suggest Observatory all the way to Sea Point – would get quite a lot of pushback I imagine. My answer is if you want a single family home you should move further out like everyone else does in every other workable city in the world.

In practice this would probably mean you cannot renovate an old property without converting it into a multi-family home, or policies to that effect. If you want to invest in an Airbnb in that area, you pay an additional tax which will offset the social problems caused by taking inventory out of the city’s housing market. The City itself should use whatever levers it can to ensure more middle-income housing is built.

The financializstion of housing in London more specifically and England more broadly stands as a future warning to Cape Town about the dire consequences of having large capital parked in housing at the expense of investment in developing business (productivity). As the Economics Observatory notes:

“Research on the reasons for this poor performance has often failed to look at how people’s housing costs, locations and living conditions might affect their productivity – for example, through their proximity to jobs that match their skills. Across the economy as a whole, housing prices can influence productivity levels by encouraging or discouraging investments in technology, innovation and new businesses. The sustained failure to explore the economic consequences of housing systems and outcomes arises from the complex nature of housing, housing markets and their inherently ‘local’ dimension.”

In short, does the City of Cape Town want a vibrant and productive city across the board where young people and families can thrive or do they want rich Europeans and their fancy parties for six months of the year?

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend