I probably wouldn’t have known the Miss SA pageant was happening – just not my thing – had it not been for the noise around one of the contestants, Ms Chidimma Adetshina. Her father is Nigerian, and her mother from Mozambique. This has not gone down well in some quarters.

“Miss South Africa must represent the best of what it means to be a young South African woman,” said Patriotic Alliance grandee and MMC for Transport in Johannesburg Kenny Kunene. He added that his party, which has made securing South Africa’s borders and expelling illegal immigrants top of its agenda, was “pursuing legal avenues to get to the bottom of this matter, including Adetshina’s participation, if necessary.” The party’s ebullient leader and South Africa’s Sports, Arts and Culture minister, Gayton McKenzie, chimed in, demanding to know the truth about her status.

How do we, each of us individually and all of us collectively, fit into a society? What does it mean to be a “citizen”? This is a perennial question, possibly the most elemental of all for any civilisation. It’s an especially important matter for societies with deep divisions and severe stresses.

What legitimises us within a society? What makes us belong? What does it mean to be a “South African”? The relationship between a country and the individual is expressed in the idea of citizenship. As this is often phrased, it’s about the “documentation”, and whether the state has extended to the individual the legal claim on citizenship – the right to belong.

So, in Adetshina’s case, much ado has been made about whether she is, in fact, legally South African. So far, the assumption has been that she is a South African citizen who has the necessary papers to prove it. But whether or not she is legally a citizen of South Africa is hardly the concern of her detractors. Rather, it is her origins and ancestry that place her outside the national community.

Historically, citizenship has been – or, in an ideal expression, it should be – a statement of belonging among people sharing a common moment in history and geopolitics. All citizenship imposes boundaries between those it includes and those it excludes; to be a citizen of one polity implies that one is not a citizen of another. Over time, different societies have evolved different means of determining the criteria for inclusion and exclusion.

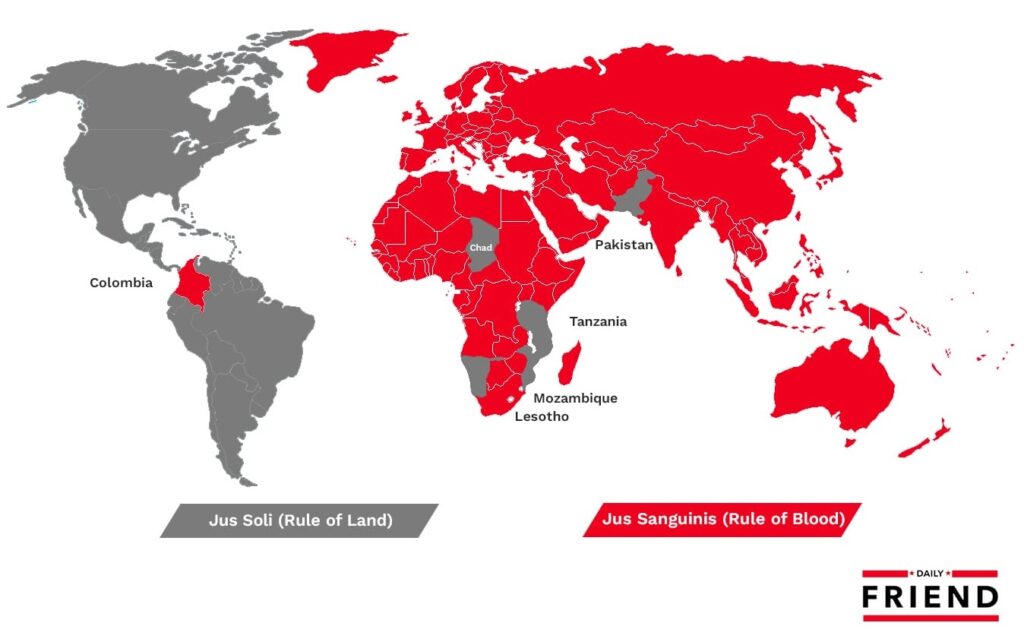

Two broad schools exist for conferring citizenship. The first is so-called jus soli, the “right of soil”, which extends it on the basis of birth. To be born on the country’s soil, in other words, makes a person ipso facto a citizen of the country. This is a model most strongly connected with the United States and the Western hemisphere more broadly.

The second is jus sanguinis, the “right of blood” which grants citizenship primarily on the basis of ancestry. To be born to citizen parents is to be inducted into the political community, which is often conceptualised – or has been conceptualised historically – as a culturally determined entity. Jus sanguinis is associated with Europe, as well as with a number of states in Asia.

In practice, and in deference to the realities of migration in the modern world, most countries apply elements of each model. This includes South Africa.

More interesting here, though, is the sense of national identity that each approach assumes. Jus sanguinis is associated with nationalisms built on ascriptive identities, or what might be termed ethnic nationalism. To be a member of the national community is to practise a particular culture, to speak a certain language, to enjoy certain forms of recreation and art, and to worship a particular deity.

It’s a view of society that values the cohesion on factors that are visceral and irrational – and for those reasons, often highly durable. Ethnic nationalism is one that is able to call on the instinctive solidarity that is produced by numerous overlapping commonalities of identity that a group sees as “its own”.

Jus soli, by contrast, is associated the idea of civic nationalism. It grants membership to those within its geographical borders without distinction of ancestry or other ascriptive characteristics (in practice, historically, this was a process that took generations to develop as various out-groups, such as women, slaves and ethno-religious minorities were included). Its standard for acceptance is premised on loyalty to a set of values and symbols.

Civic nationalism would demand that people respect the governance and political institutions of their country. Where the state makes demands on the population, these are to be rationally articulated, and all those eligible to respond are expected to do so. Civic nationalism is in a sense a very generous idea. It has the potential to encompass a broad range of personal diversity, with its criteria narrowly focused on what is relevant for the public good.

The Adetshina controversy pushes these competing conceptions before South Africa. The premise of post-1994 South Africa was that a new identity – open, accommodating, optimistic – would be founded on fundamentally civic grounds. This represented the only option available for reconciling competing identities (and nationalisms) that had long been grounded in race and ethnicity. One’s origins would be of little real account outside the private sphere and within whatever free associations people care to form; in the public sphere, citizenship would rest on universal, constitutional principles to which all could lay claim. Citizenship and participation were open to those of all ancestry, and in principle to those who wished subsequently to join the polity.

This recalled George Washington’s letter to the Jewish congregation of Rhode Island, that the United States had “given to mankind examples of an enlarged and liberal policy” which was founded not on mere toleration, but the recognition of rights and liberties. “For happily,” he continued, “the Government of the United States gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens, in giving it on all occasions their effectual support.”

Yet the development of South Africa since 1994 (as indeed, the experience of the US over its history) has shown the frailties of this.

The pull of racial and ethnic loyalties – and their deliberate manipulation – have been strong indeed. Racially-coded policies were bound to work against the sense of civic identity and to incentivise racial variants. This was arguably inherent in the ANC’s whole policy trajectory, which it defined as being motivated by the interests of black people in general and Africans in particular. With the ascendency of President Thabo Mbeki, explicit appeals to race and racial interests became ever more common and intellectualised.

Such divisions having been legitimised, the question of what to make of those without an ancestral tie to South Africa – in other words, those who tend to be called “foreign nationals” – would predictably become a fraught one. This is the case even where a naturalisation process has been undertaken and formal citizenship acquired. After all, if a civic conception of citizenship had failed to take universal root among South Africa’s own population, people at least broadly familiar with one another, a sense of suspicion and exclusion towards those from distant parts was all but inevitable.

This was all the more the case where “foreigners” came to live alongside stressed and deprived communities, and could supply an identifiable face to their misfortunes. Hence the hostility to Adetshina. Her citizenship notwithstanding, she is a perpetual “Nigerian”: not one of us, and never able to be, and an avatar of what ails the country.

It represents an insidious mutant ethnicised view of citizenship, or, technically, what is described as “nativism”.

The threat this poses to all of us cannot be overstated. A civic conception of citizenship is the only viable one for a society like South Africa. Incentives to view citizenship and the belonging it signifies in other terms undermines societal cohesion. Note too that this is not merely about whether “foreign nationals” (even naturalised citizens) belong or not, but whether any of us do. Exclusionary senses of identity invariably jump borders. What starts with the “Nigerians” easily becomes about the “Boers” and then about the “Indians” – or whatever group one cares to name.

The reckless invocation of identitarianism has already done great damage to the country.

This is not to say that ethnic or any other sectarian identities would be unimportant in a plural society – merely that in relation to the state, a civic conceptualisation should determine one’s legitimate state and sense of belonging.

Nor is this an argument against the existence of borders or the rights of states to set their own conditions for citizenship. Indeed, a recent revelation indicates that there may have been citizenship fraud on Adetshina’s mother’s side. Adetshina herself would not have been involved in this – the Department of Home Affairs has been clear on this – and it is unclear whether this has an impact on her own citizenship. Sadly, malfunctioning systems do nothing to inspire confidence in the institutions around which a sense of civic citizenship turns, and it is precisely such revelations that will likely bolster the dangerous demands for exclusion that we’ve seen in this case.

Perhaps sadly – at least for the aspirations of a young lady – Adetshina has withdrawn from the pageant. Her participation may have ended, but the matters prompted by it have not. All of which makes a debate around a pageant a remarkably important one.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend.