Quack remedies like buchu extract are as old as the hills. Marketing them is a well-honed skill. Here’s what to look out for.

In the second half of the 19th century, makers of patent medicines almost single-handedly funded the rise of the newspaper industry. Much of the advertising carried by newspapers of the day extolled the virtues of various proprietary preparations for the cure of ailments ranging from headaches and fatigue to diabetes and syphilis.

This is why patent medicines get an honourable mention in the history of advertising.

Patent medicines are brand-name preparations that are not prescribed by doctors or pharmacists, and whose composition is often not disclosed. They were sold at medicine shows that combined entertainment with promotion of the patent concoction, where paid shills in the audience would often provide astonishing testimonials of the efficacy of the wonder elixir.

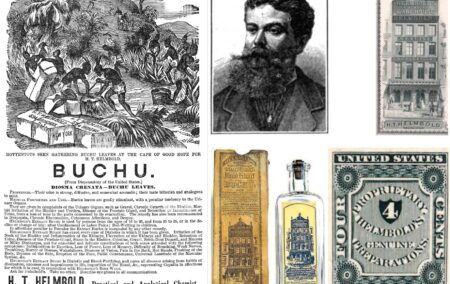

One of the pioneers of this industry, Henry T. Helmbold, sold a concoction known as “Helmbold’s Highly Concentrated Compound Fluid Extract of Buchu”.

Buchu – also known as boegoe and a variety of other non-standard spellings – was introduced into Europe and America from South Africa, where the Khoi-San had been using it for centuries as a general antiseptic, and internally to treat urinary tract infections, kidney complaints, colds, stomach upsets, rheumatism, gout and fever.

Power of advertising

Helmbold was one of the first patent medicine sellers to recognise the power of spending great fortunes on newspaper advertising. Between 1846, when he first produced his buchu extract, and 1865, he turned it into the best-selling patent medicine in the US.

Helmbold’s strategy was to soften up his target market by conjuring scary images of various diseases in their heads, and appealing to natural hypochondria by describing a multitude of vague and non-specific symptoms, some of which almost all his audience could recognise in themselves.

He would drop pamphlets entitled “The Patient’s Guide, A Treatise on Diseases of Sexual Organs” that described symptoms such as “restlessness” and “the inability to contemplate disease without a feeling of horror” which, if left untreated (by buchu of course) could lead to epilepsy, insanity, or consumption.

Advertising extolled the value of Helmbold’s extract for any and all complaints related to the urinary system, up to and including “loss of tone in the parts concerned in its evacuation”, which sounds suspiciously like a reference to erectile dysfunction.

In addition, Helmbold’s preparation could cure dyspepsia, rheumatism, skin conditions, dropsy (oedema or fluid retention), labour pains, bedwetting in children, “affections peculiar to Females”, “every case of Diabetes in which it has been given” and prostate complaints.

For good measure, the advertisements added: “…and for enfeebled and delicate constitutions of both sexes attended with the following symptoms: Indisposition to Exertion, Loss of Power, Loss of Memory, Difficulty of Breathing, Weak Nerves, Trembling, Horror of Disease, Wakefulness, Dimness of Vision, Pain in the Back, Hot Hands, Flushing of the Body, Dryness of the Skin, Eruption of the Face, Pallid Countenance, Universal Lassitude of the Muscular System, &c.”

Everyone needed buchu extract, for everything.

Clinical trials

Today, we have protocols and procedures that test these sorts of claims. They’re not perfect, but randomised controlled clinical trials, properly blinded, are fairly good at determining whether a given medicine works better than a placebo, or whether one medicine works better than another.

They can also uncover negative side-effects, which means we can assess the relative merits of taking a medicine, given on one hand the effects of disease, and on the other the risk of side-effects.

Multiple well-designed clinical trials across a large number and wide variety of patients are the gold standard in determining the efficacy and safety of modern medicine.

Although there is some evidence for the efficacy of buchu for urinary tract infections and related ailments, it has become obsolete with the advent of inexpensive and effective antibiotics.

A 2022 paper by Thomas Brendler and Mona Abdel-Tawab assesses the state of research on buchu. It also contains a fascinating, detailed history of the medicinal use of buchu.

It concludes: “Limitations in the hitherto conducted research lie in the undisclosed composition of the buchu extracts used and the difficulty in extrapolating data from animal studies to humans. Health claims for buchu products need to be substantiated by randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled studies. Only then can they be promoted for their true therapeutic potential.”

Lessons

We can learn a lot from patent medicine men like Helmbold and other snake-oil sellers. They all use predictable and recognisable tactics to convince people that their preparation – and their concoction alone – will cure them of the most obscure and intractable complaints.

Here’s a list of red flags that you’re being swindled by a vendor of quack medicine.

Anyone who says “Big Pharma” is likely trying to deceive you. The pharmaceutical industry is large, diverse and highly competitive. It is also one of the most over-regulated industries in the world to ensure patient safety. The reason you know cases like Thalidomide and Vioxx by name is because they are so rare, not because this commonly happens with the 20 000 or so drugs that are currently licenced for use.

Anyone who says there’s a conspiracy to hide the truth, or they have a secret that doctors don’t want you to know, is swindling you. If doctors knew a cure for your particular cancer, you can be sure they’d offer it in a heartbeat. If an upstart pharmaceutical company could do so, it would patent it and make a fortune.

Claims that doctors and drug companies are in it for the money are, well, true. But they’re also true for naturopaths, alternative health shops, chiropractors, homeopaths and any other quack. Unlike the quacks, however, the doctors and drug companies are well-regulated and backed up by published science that others can review, replicate or falsify.

Testimonials

Testimonials are probably the biggest giveaway that what you’re about to buy is a phony cure. Vendors of genuine medicines do not need the word of Sharon from Orkney or Sipho from Khayelitsha that they work, because they have randomised controlled trials to point to.

There is no way to ascertain whether Sharon or Sipho exist, or whether they really said what it says on the box.

If they are, and they did, anecdotal evidence is just that: anecdotal. The plural of anecdote is not data.

Isolated anecdotes are not statistically significant. It is easy to cherry-pick two or three apparent successes out of a hundred failures and use those testimonials to claim your product works. They might just be down to chance.

Testimonials don’t even offer proof that the effect was produced by the product that’s being sold.

“I took this flu remedy, and three days later, I was cured!”

Yeah, sure. That’s what the body does. It recovers from flu. Unless it was an expensive modern anti-viral, the “remedy” likely had nothing to do with it.

Natural

The word “natural” should be a red flag. There is no law that says natural ingredients are somehow better than “chemical” ingredients. In fact, all natural ingredients are chemical ingredients.

Scientists have studied many substances, and they found that about half of them are to some degree carcinogenic. Whether they are natural or synthetic makes no difference. Arsenic and cyanide are perfectly natural, as are nettles, poison oak, capsicum, asbestos, mercury, anthrax, botulism, formaldehyde, and nuclear radiation.

The downside of “natural” remedies is that they contain not only the active ingredient, but also a lot of other ingredients that co-occur with them in nature. Even if the active ingredient has been studied, most of the others probably have not. In addition, ensuring the correct dose of the active ingredient is very hard when you’re preparing some herbal concoction.

All these problems and more are resolved by a scientific process of isolating the active ingredient, testing that ingredient at varying doses, documenting reactions both beneficial and adverse, and manufacturing uncontaminated medicines at accurate doses, with detailed clinical information for both doctors and patients.

Too good to be true

Anything that claims to be a miracle cure most definitely isn’t. If something promises that it can cure intractable conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes or cancer, that promise is extremely unlikely to be true.

If it promises breakthroughs that are undocumented in the medical literature, you’re being had. If it promises you an easy and quick path to health (or weight-loss), you’re being sold a placebo.

If there really had been a scientific breakthrough, you would find it in the medical literature, and conventional medicine companies would be all over it. You will not hear about it first from your local hippie herbalist.

Proprietary or secret formulas, unique to the seller, are a dead giveaway of quackery. Medicines should have all their ingredients, and their effects, documented in detail.

Appeals to ancient wisdom are also highly suspect. Ancient wisdom that works has largely been incorporated into modern medicine.

A great deal of ancient wisdom, however, is patently wrong. The ancients believed, mistakenly, in the four-humour theory of disease, the influence of the moon and stars, mercury for syphilis, animal dung poultices, cannibalistic corpse medicine, “wandering wombs”, trepanning, demonic possession, and, of course, magic.

They didn’t believe in hygiene, which alongside antibiotics is probably the most important advance in medical practice in the 20th century.

Old knowledge is not necessarily good knowledge. On the contrary, the scientific method allows us to learn and improve on the poor knowledge of the past.

Nonsense words

If you see the words detoxfication, immune system boosting, helping your body heal itself, balancing pH or balancing anything else, you’re looking at a concoction that you don’t need.

The body does all that naturally. The liver and kidneys detoxify the body. The immune system can be improved by vaccination, but not by drinking random herbal concoctions. If you could significantly affect the pH of your body, or your blood, you’d be dead by now; the body keeps a near-perfect balance automatically. And healing itself, well, yes, that’s what the body does. All you need to help that along is a healthy, varied diet of fresh food, plenty fluids, and rest.

Many quacks will try to dazzle you with scientific-sounding terms like quantum, energy, vibrations, or electromagnetism. They’re nonsense.

Quantum testing can be done, but you wouldn’t learn anything about your body’s health, and you’d need a particle collider like those they have at the European Organisation for Nuclear Research (CERN).

Many adjectives before the word “medicine” are indicators of skulduggery. That includes words like alternative, holistic and complementary.

As Tim Minchin so eloquently said, “By definition, alternative medicine has either not been proved to work, or been proved not to work. Do you know what they call alternative medicine that’s been proved to work? Medicine.”

Hard sell

Any product that is advertised with a “hard sell” technique is to be avoided. This refers to insistent, aggressive or high-pressure sales pitches, often found online or on television.

Words like “act now”, “limited stock”, “lock in this one-time-only price” or “if you buy now you get X free”, are tell-tale signs that you’re being manipulated by people who are trying to badger you into a poor decision.

Claims that a product treats a long list of ailments, many of them vague and general, are also red flags. Real medicine treats a limited set of specific conditions, usually in a well-understood manner.

Everyone periodically suffers headaches, body aches, fatigue, heartburn, dizziness or insomnia. These sorts of symptoms could have any number of causes, or no cause at all. If you think you’re ill, go see a real doctor, instead of buying a miracle cure-all.

Also avoid anything that you’re urged to take not only to cure a condition, but to prevent it. There’s nothing a quack likes more than convincing people to provide them with steady monthly income for life.

Skepticism

It is reasonable to be skeptical of modern medicine. It doesn’t have answers for many medical problems, has poor answers for many more, and has not always been the most ethical of businesses in the past.

Problems like over-prescribing antibiotics, tranquilizers or painkillers are a lot more complicated than simple malfeasance by greedy practitioners, but they did happen (although they’re much less common nowadays).

Would that people had the same skepticism towards quack medicine, however. Unlike with conventional medicine, quacks don’t even try to offer scientific evidence of efficacy or safety.

They’re just as much motivated by material greed, and they are invariably endowed with more charisma than with honesty or actual medical knowledge.

Buchu extract and snake oil weren’t aberrations. There was a time when almost all medicine was quackery. Fortunately, thanks to the rise of scientific medicine, we no longer need to be victims of ignorance, charlatanism and dishonesty. You just need to know what to look out for.

[Image: Buchu.webp – Henry T. Helmbold was an American pioneer of patent medicines who popularised buchu extracts harvested in South Africa. Public domain images.]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend.