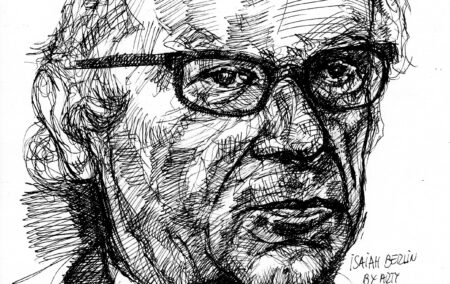

In his famous lecture, “Two concepts of liberty”, Isaiah Berlin introduced the now trite distinction between so-called “positive” and “negative” freedom.

This distinction remains applicable today, but naturally the words “positive” and “negative” have predictably developed positive and negative connotations, which obscures the nature of the underlying concepts. Talking about liberal freedom as “negative” and progressivist dependence as “positive” has obviously not been good to the cause of liberty.

This article presents three conceptions of freedom that do not utilise the now loaded words of “positive” or “negative,” linked to the three main schools of thought in the West that at least rhetorically concern themselves with liberty.

It goes without saying that the nature of modern political advocacy means there are thinkers and activists who straddle two or all three of these conceptions at least to some degree.

FA Hayek, for example, is one of the foremost classical liberals and provided some of the most lucid arguments for tolerance (or allowance), yet made some provision (errantly, in my view) for government empowerment. John Stuart Mill, on the other hand, made some very quotable arguments for classical liberal freedom, especially in the realm of expression, but was perhaps the first notable liberal-turned-progressive.

Classical liberal (or libertarian) freedom: Tolerance

Of the three conceptions, the classical liberal – or, to use the American term, “libertarian” – conception, is the simplest, and requires the least elaboration.

Freedom means the individual is tolerated (or allowed) to do whatever they please, provided that in so doing they tolerate the very same freedom of others.

According to this conception, the government (and all others) are under the mere obligation to tolerate individuals as they conduct themselves freely. Government in particular must protect the tolerance – in other words, if someone disallows another from being free without the latter’s consent, government must step in via the police and the courts.

In this respect, classical liberals often speak of so-called “equality of opportunity,” which is perhaps an inapt synonym for the more appropriate “freedom to try”.

Classical liberals locate the entitlement to be free in the nature of being human: freedom is God-ordained, or the reality of individuality – separate thinking and accountable consciousnesses – ordain every person with the right to not be subjected to the will of another without prior agreement.

This is Berlin’s “negative” conception of liberty.

Hayek traces the classical liberal conception of freedom from the Greeks through the Romans, the Spanish, Dutch, Italians, and ultimately to the British and Americans. The Scottish moral philosophers, like Adam Smith, are credited with developing the intellectual foundation of classical liberal freedom. It is this conception of liberalism that South Africa inherited, through the Scottish missionary John Philip, a devoted follower of Smith’s work.

Progressive (or social-democratic) freedom: Empowerment

The next conception of freedom, in many ways, grew out of the rhetoric of the first, although it was significantly influenced by illiberal (indeed, proto-totalitarian) sentiments expressed during the French Revolution by those who sought to replace Christianity with the secular religion of state-worship.

I object to the proponents of this philosophy being described as “liberals,” but this has caught on after the time of their arguable progenitor, John Stuart Mill.

The progressive conception of freedom is akin to the classical liberal conception but with a key difference.

Freedom means the individual is empowered to do whatever they please, provided that when so doing everyone else is able to exercise the very same freedom.

The focus here is on equality, in the sense that if a person is unable to fulfil their freedom on equal terms with all others, government must step in to set the inequality right.

According to this conception, the government (and often others) are under the substantive obligation to empower individuals to enjoy their freedom. Progressives concede that the road to this utopia, where everyone is equally able to enjoy freedom, might include government tramping on (liberal) freedom to achieve equality.

In this respect, progressives believe in so-called “equality of outcome” or “substantive equality.”

This is Berlin’s “positive” concept of liberty.

Hayek traces this conception of liberalism to the French Revolution, which was identified more closely with democratic thinking than with the thinking focused on individual liberty evident in the British tradition. It was, however, through John Stuart Mill (and before him, Thomas Paine) that even classic British liberalism to an extent became enmeshed with progressivism. Hayek writes:

“[I]n his celebrated book On Liberty (1859), [Mill] directed his criticism chiefly against the tyranny of opinion rather than the actions of government, and by his advocacy of distributive justice and a general sympathetic attitude towards socialist aspirations in some of his other works, prepared the gradual transition of a large part of the liberal intellectuals to a moderate socialism.”

Through the influence of Millites TH Green and LT Hobhouse, the Liberal Party in Britain (which Hayek himself believed was the best expression of classical liberal politics beforehand) changed its character around the turn of the previous century in favour of social and economic interference.

In his favourable introduction to Hobhouse’s Liberalism, Alan P Grimes writes that Hobhouse engaged in a “reformulation of liberalism” away from the philosophy of “freedom of trade and of contract” towards one where the issue was not “man against the state, but of men working through the state as an instrument of social organization to achieve personal and social fulfillment.” Grimes writes:

“At bottom, Hobhouse’s Liberalism sought such a reconstruction of social philosophy as would preserve the essentials of individuals in an economy basically oriented to socialism; he sought to achieve a ‘Liberal Socialism.’ Eschewing laissez-faire liberalism on the one hand, and doctrinaire, economically deterministic socialism on the other, he sought to justify in theory that which was largely achieved in substance in both England and the United States half a century earlier: the rudiments of the liberal welfare-state.”

The classical liberal Ludwig von Mises responded ably to this “reformulation” in his identically named work, Liberalism, as follows:

“Nor can the programs and actions of those parties that today call themselves liberal provide us with any enlightenment concerning the nature of true liberalism. It has already been mentioned that even in England what is understood as liberalism today bears a much greater resemblance to Toryism and socialism than to the old program of the freetraders. If there are liberals who find it compatible with their liberalism to endorse the nationalization of railroads, of mines, and of other enterprises, and even to support protective tariffs, one can easily see that nowadays nothing is left of liberalism but the name.”

Mises rightly problematised how social democrats had succeeded in bastardising the name “liberal.” But we are now in the fortunate position of progressives increasingly abandoning the monicker because they (mercifully), like everything else, are beginning to regard liberalism as representative of racism, sexism, and various other forms of bigotry. This is a grand opportunity to reclaim the philosophy from the worshippers of social engineering and violence.

National-conservative (or postliberal) freedom: Collective advancement

The final conception of freedom is that of the so-called “national-conservatives.” I distinguish between these and other “conservatives” because many Western conservatives are simply “liberals” who wish to avoid the unfortunate socialistic associations introduced to that term by progressives.

The national-conservative conception of freedom is entirely relative. Whereas classical liberals believe that there is a universal, timeless nature to freedom that is as coherent today as it was in 5000 BC, national-conservatives argue that freedom is necessarily the construct of a given society.

Because we are dealing here primarily with national-conservatives in the West, their definition of freedom will often be very similar to that of classical liberals, but they would argue that it is unique to the West and that it does not necessarily apply elsewhere, or even in the West at different times.

National-conservatives necessarily straddle the line between the classical liberal and progressive conceptions of freedom, because both of these conceptions are influential in the West. Because this “hybrid” freedom that the West is saddled with is the construct of Western society, it is not uncommon for national-conservatives to favour certain characteristics of the welfare state, while also valuing individual liberty.

When the classical liberal conception of freedom was dominant, national-conservatives sought to conserve that in particular. In some societies, where the progressive notion of freedom is becoming dominant, future national-conservatives will seek to conserve that conception in particular. More likely, national-conservatives will conserve an entirely pragmatic conception of freedom that takes from both, depending on what advances the interests of the nation.

To national-conservatives, freedom is not an inherent entitlement of being human, but rather a product of social and cultural dynamics. Yoram Hazony writes in Conservatism: A Rediscovery, criticising classical liberalism:

“And this insistence on individual freedom as a dogma, as ‘the supreme principle’ and the ‘highest ideal’ of politics, is not something that can be reconciled with an empiricist or conservative political outlook. It is a statement of a liberal faith that is intended to override evidence and argument.”

The Edmund Burke Foundation similarly sets out the relativist approach to freedom, that is entirely dependent on the predominant circumstances existing in “the nation” at the time:

“We believe that an economy based on private property and free enterprise is best suited to promoting the prosperity of the nation and accords with traditions of individual liberty that are central to the Anglo-American political tradition. We reject the socialist principle, which supposes that the economic activity of the nation can be conducted in accordance with a rational plan dictated by the state. But the free market cannot be absolute. Economic policy must serve the general welfare of the nation.”

Perhaps stated in a way that would clearly manifest its differences from liberal and progressive freedom, national-conservative freedom is the notion that one may – and perhaps, must – do that which advances the interests of the nation. It is a freedom that is, in other words, abstracted from the self-interests of the individual, and manifests only within the context of a defined collective. As Prof Danie Goosen writes, “Freedom emerges where the individual has cultivated herself through traditional institutions and the virtues inherent in them.”

Although Berlin did not have a separate category for national-conservative thinking around freedom, it is worth noting here, because this conception of freedom is becoming more popular with the rise of populism in the West.

Back to coherence

As with any other concept, for it to be of use, “freedom” has to mean something other than “good stuff.” For freedom to be useful as a social concept, it must be distinguished from the other good and noble things we want to pursue and achieve in society.

The progressive conception of freedom is necessarily precarious. It relied on the liberal elevation of the individual to a matter of political concern, then twisted that to pursue totalitarian ends. Even today, it relies on liberal sentiments to prosecute its agenda of homogenisation and the elimination of difference.

The notion of empowering an individual to live out their honest desires is laudable, but is – as it always has been – a matter of personal and communal responsibility, not liberty. And when this empowerment is made synonymous with freedom, it does (and must) eliminate freedom-as-tolerance in the process.

The national-conservative conception of freedom, on the other hand, is shaky because of its inherent relativism. If an Arab woman, living 100% in line with the religio-cultural requirements of her community, but desiring nothing more than to leave and pursue a self-motivated life elsewhere, can be described as “free” even while her husband and father threaten her with certain death if she steps out of line, that is a positively useless notion of liberty.

Only the liberal conception of freedom, ultimately, makes coherent sense. This is unsurprising, for liberalism is the philosophy of liberty. Freedom is its focus, whereas in both the cases of progressivism and national-conservatism other factors weigh heavier.

And what counts in classical liberalism’s favour is that its conception of freedom is fully compatible with both the progressive and national-conservative agendas. The progressive desire to empower can live comfortably within the framework of liberal tolerance provided the very same principle of tolerance is observed: empower, but do not impose (this is what we call charity).

Similarly, the national-conservative desire to elevate community interests beyond the consumerist whims of individual self-interest can just as easily reside within liberal order. Any community can self-organise, and enforce rules that require individuals to march to the community’s tune, provided that community does not try to impose itself on another community, and provided it allows individuals within it to exit.

These are not “limitations” that liberalism imposes on progressivism or national-conservatism any more than it is a “limitation” on a person’s liberty when they are told that they may have consensual sex with a willing partner, but must disengage where consent and willingness are absent. Voluntariness is a natural human imperative, not a burden.

But there is perhaps a simpler reason for why classical liberal freedom is, in the final analysis, the only valid conception of freedom. If “doing whatever you please, provided you tolerate the same for others” is not freedom, then the question arises: what is it?

What is the phenomenon of a person being allowed to do what they desire while not imposing their desires on those around them? What is the word, or terminology, of this?

The unavoidable and irresistible answer, which even progressives and national-conservatives must concede, is that this is pure and unadulterated freedom. This phenomenon does not only sit, comfortably, 1:1, within the terminology of liberty, but it is its very definition.

[Image: Arturo Espinosa – https://www.flickr.com/photos/espinosa_rosique/8284855889, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=74361949]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend