Was Caesar born by caesarian section? Did Einstein fail maths at school? Does watering plants in sunlight burn them? Did Marie Antoinette say, “Let them eat cake”?

Myths, misunderstandings and urban legends are all around us. To maintain a skeptical attitude towards so-called common knowledge, or things people suppose to be true, helps to hone our critical thinking skills.

Here’s another list of ten things that satisfy the adage: “It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

1. Albert Einstein failed maths at school

Many an intelligent but lazy school kid talked back to their teachers or parents, declaring that Albert Einstein failed mathematics at school. The implication being that natural genius transcends mere rote learning, and that you can perform poorly at school and still be successful.

This argument falls in the same category as the successful dropout meme: that Steve Jobs (or Richard Branson, or Simon Cowell, or Walt Disney, or Aretha Franklin, or Quincy Jones, or George Foreman, or Quentin Tarantino, or Ray Kroc, or Coco Chanel, or any of a few dozen others) never finished high school shows that you don’t need to do well at school to succeed in life or business.

The fallacy, of course, in both these cases, is that this is anecdotal cherry-picking. Very few high school dropouts go on to great success, compared with their high-achieving peers. On average, high school dropouts do not succeed anywhere near as often as those who put in the effort and matriculate with good marks.

The examples cited are exceptions to the rule, and they succeed despite poor formal education because they are exceptional people. The chance that the school kid who shirks their work turns out to be an Einstein-level genius is, frankly, slim.

That said, it isn’t true that Einstein failed mathematics at school.

Anyone who is even superficially familiar with Einstein’s four 1905 papers (one of which earned him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921), written in the year he turned 26, will recognise that these are not likely to be the product of someone who a mere ten years earlier was a mathematical slouch.

The rumour that he failed school mathematics dates back to a Ripley’s Believe It or Not newspaper column which reported, “Greatest living mathematician failed in mathematics.”

Upon being shown this column in 1935, Einstein laughed, and retorted that he had never failed in mathematics. “Before I was 15 I had mastered differential and integral calculus,” he said.

Accounts from his family confirm that not only was he at the top of his class in mathematics (though not in his other subjects), but he routinely studied higher mathematics on his own, and developed proofs well outside the scope of his schoolwork. One shouldn’t need to belabour the point, but Einstein was extremely good at both mathematics and later, physics.

The origin of the myth of his poor school performance is hard to pinpoint. It may have been people’s misunderstanding of the marking system, which during his time at school switched from 1 being the highest mark and 6 being the lowest, to the exact opposite.

It could also have originated with his negative experience of school discipline, and the disdain of teachers who felt intimidated by his intellect. They interpreted it as a lack of respect, declaring that he would not make much of himself.

It may have been an embroidery upon Einstein’s statement that he “believe[s] in intuitions and inspirations”. In an interview in 1929, he said: “I am enough of the artist to draw freely upon my imagination. Imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world.”

Wherever Ripley’s got their factoid, however, it was wrong. Einstein never failed maths at school.

2. Hair of the dog (or water) cures a hangover

It is commonly believed that a drink the next morning (“hair of the dog”) will cure you of the hangover that resulted from the previous night’s excess.

It is also believed that hangovers are largely the result of dehydration, so drinking sufficient water after drinking alcohol can reduce or prevent hangover symptoms.

Neither of these is likely to be true to any significant degree.

Alcohol has been an extraordinarily popular drug for thousands of years, plays a very significant role in modern society, underlies a great many ailments, physical, mental and social, comprises an enormous industry and a large source of revenue for the state, causes a significant number of injuries and deaths to innocent bystanders, and widely impacts economic productivity.

It is startling, therefore, to discover that one of the most common sequels of alcohol consumption, the common hangover, has been the subject of only a limited number of studies, and remains fairly poorly understood.

Hangovers reach their worst symptoms when the ethanol in a drink has been fully metabolised, and the blood alcohol level reaches zero. After this, symptoms can persist for many hours, or even days.

There are multiple theories about what exactly causes hangovers, though it appears that dehydration is a coincidental after-effect of alcohol consumption which does not play a significant role in hangovers.

One theory holds that the severity of a hangover is in part determined by the presence of congeners – substances other than ethanol, such as methanol, polyphenols and histamine – in a drink. This may explain why pure ethanol in a mixed drink causes very little by way of hangovers, but dark spirits like brandy and bourbon cause fairly severe hangovers.

Ethanol is metabolised into acetaldehyde, which is toxic, and is in turn broken down into acetic acid, but this doesn’t seem to be the full explanation. Methanol, by contrast, is broken down into formaldehyde and formic acid, which are far more toxic.

This may also explain why a drink the next morning appears to reduce hangover symptoms: the newly introduced ethanol blocks (or rather, postpones) the formation of the metabolic compounds of methanol, masking their toxic effects on the body.

There are many other causes of hangover symptoms, however, since alcohol has numerous disruptive effects on various bodily processes. Rehydration alone doesn’t cure hangover symptoms, and neither does the hair of the dog the next morning.

Ultimately, the only way to avoid hangovers is not to drink to excess.

As an interesting aside, the phrase “hair of the dog”, short for “a hair of the dog that bit me”, dates back to the 16th century. At the time, and in complete ignorance of the germ theory of disease, it was believed that hair from the dog that bit you, when placed into the bite wound, could prevent rabies.

This belief was based on the ancient Greek dictum that similia similibus curantur, or “like cures like”. Today, this is one of the pillars of the pseudo-scientific practice of homeopathy.

3. Fortune cookies are a Chinese tradition

If you go to a Chinese restaurant in most of the English-speaking world, you may be served a fortune cookie after your meal. Made from flour, sugar, vanilla, and sesame seed oil, the crispy, hollow cookie conceals a strip of paper with a vague prediction, a clever quotation, a set of lucky numbers, or a phrase from ancient Chinese philosophy on it.

If, however, you go to a Chinese restaurant – that is, a restaurant in China – you will likely not receive a fortune cookie.

The history of fortune cookies is murky, but their modern popularity likely started with restaurants run by immigrants to California in the 19th century.

If there is a deeper national history to fortune cookies, it is likely that it is Japanese, and not Chinese. There is historical evidence of cookies baked in Japan that are very reminiscent of (though not identical to) the modern “Chinese” fortune cookie. That would make the tradition Japanese, and not Chinese.

4. You lose most of your body heat through your head

If you’ve studied physics, this claim will sound suspicious. Heat transfer ought to be roughly proportional to surface area, and not to which limb is exposed. It is, perhaps, plausible that the scalp contains more blood vessels than other body parts, but then, the head is also covered by hair (in some people).

The myth has multiple origins. Before convenient heating, people used to wear nightcaps. Mothers will tell children to put on a hat before going out into the cold. And a military experiment in the 1950s did indeed find that soldiers in frigid conditions lost most of their body heat through their heads.

What reports on that experiment didn’t make clear is that the subjects were dressed in arctic survival gear. If you insulate all of the body, then it stands to reason that the sole uninsulated part will be the cause of most of the heat loss.

If those experiments had been conducted in swimsuits, then the head would have accounted for about 10% of the loss of body heat, which is proportional to the surface area of the body that it represents. The head is not special; it is just the last part of the body to get covered when it’s cold.

5. Marie Antoinette said, “Let them eat cake,” out of disdain for the poor

Marie Antoinette was the youthful wife of the French king who would be deposed by the French revolution of 1789. Aged only 14 at the time of her marriage to the then-Dauphin, Louis XVI, in 1770, she became queen of France when her husband ascended to the throne in 1774.

Marie Antoinette was very unpopular with the people. She was justly seen as profligate, as well as disloyal, both to her husband the king and to her country. It is certainly plausible that she told the peasants to stuff it when they complained about the high price of bread, but as it happens, the “let them eat cake” quotation precedes her.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau mentioned the phrase in his 1767 work, Confessions, in recalling an incident from 1740, when he stole some wine but didn’t have any bread to go with it.

“Finally I remembered the way out suggested by a great princess when told that the peasants had no bread: ‘Well, let them eat cake,’” he wrote, using the word “brioche”, which refers to a type of pastry.

The incident Rousseau recalled happened 15 years before Marie Antoinette was even born, and he likely wrote it down in 1766, when she was 10 and still living in her native Austria. There is no historical evidence that she ever repeated the phrase.

6. Touching a frog will give you warts

A persistent myth that was certainly common when I was growing up was that touching a frog could give you warts. Some versions were specific: the urine of a frog would cause the warts.

This is not true. Although frogs do pee when they fear predation, this urine does not cause warts. Warts are caused by the human papilloma virus.

Staying away from frogs (and toads; all toads are frogs but not all frogs are toads) is still good advice, however, since a small number of frog species release toxic secretions. They are also well known to carry salmonella, which is an excellent reason not to kiss them.

7. Watering plants in the sun burns them

There’s a widespread belief that watering plants in the sun “burns” them, because the droplets act like little lenses that concentrate sunlight.

When you think about it, though, and you sketch it out, this makes no sense. The focal point of a lens is not on or near its rear surface. It is much further away. (Imagine burning something with a magnifying glass.)

Water droplets are also very small, so even if they focused sunlight on a single spot, there probably wouldn’t be enough of it to cause significant heat. Have you ever come out of the water after swimming, covered in droplets, and felt the droplets burn you?

So, what’s the deal? There is a reason not to water plants in the heat of the day, but it has nothing to do with the plants. If your plants are looking hot and droopy, watering them immediately will help them, not hurt them, no matter the weather.

The reason not to water during the heat of the day is simply that water evaporates faster when it’s warm, so less will be available for the plants to absorb. It wastes water to spray in the sun.

The best time to water plants is in the morning. Watering in the evening, which keeps plants wet overnight, can cause problems with fungal infections.

8. Hair and nails continue to grow after death

In All Quiet on the Western Front, the bleak war novel by Erich Maria Remarque, the protagonist, Paul Bäumer, imagines the decaying body of a comrade, with nails that continue to grow into corkscrews, and hair that grows “like grass in good soil”.

Ever since, the myth that nails and hair continue to grow after death – at least for a while – has persisted, and have informed lurid horror depictions of corpses.

In fact, they don’t. The vital systems of the body shut down upon death. Blood circulation stops, and cells no longer get fresh supplies of oxygen, glucose, hormones and the other building blocks of growth. Cell death occurs in a matter of hours, at most, and new cells are no longer formed.

What does happen, however, is that the skin dehydrates and shrinks, which can reveal parts of nails or hair that normally would have been covered by live skin. This can give the appearance of slightly longer hair or nails, which gave the myth legs.

9. It is dangerous to sleep with plants or flowers in the bedroom

Nosing about in a text from 1785 which extolled the fashion for large nosegays (flower bouquets worn on the bodice or around the head), and their virtue as a sensual aid to certain practices of a more indelicate nature, I was startled to discover a bold warning.

According to the learned author, a lady should never keep them in her bedchamber of a night, “for the exhalation from them is very dangerous, especially in small bedrooms”.

A lady who had neglected to remove her nosegay before falling asleep, the author reported, awoke to find herself very ill, and remained so for many days.

Not that I’m at grave risk of nocturnal exposure to the emanations of an overabundance of cut flowers, but curiosity impelled me to look into their danger.

I was disappointed to find the literature on this fascinating subject fairly sparse.

A certain Larry Hodgson, who blogs under the nom de plume Laidback Gardener, informs us that there is actually something to this. “It is not always a good idea to keep intensely fragrant flowering plants or cut flowers in the bedroom at night,” he writes. “That’s because some very fragrant blooms, even if they are often quite enjoyable during the day, can impair sleep at night, even causing nausea or headaches in very sensitive people.”

Who’d have thought? I shall immediately institute a ban on nosegays in my vicinity at night-time.

A more common belief, I discovered, is that one shouldn’t keep houseplants in the bedroom, because either they deplete oxygen in the room, or they cause carbon dioxide poisoning.

During the day, so the theory goes, plants use light for photosynthesis, absorbing carbon dioxide and releasing oxygen. At night, however, photosynthesis stops, and plant respiration consumes oxygen and produces carbon dioxide, instead.

That much is true, but research indicates that plants emit much less carbon dioxide at night than they consume during the day, so the net effect is to remove carbon dioxide and produce oxygen.

In any case, plants produce far less carbon dioxide than a single human being does, so if you’re worried about night-time air quality, kick out your partner before you eradicate your plants.

10. Julius Caesar was delivered by caesarean section

It’s in the name, isn’t it? Surely, the surgical alternative to natural childbirth is so called because Julius Caesar was born by caesarean section?

Since his mother, Aurelia, survived to witness his later triumphs, this is likely untrue. Abdominal surgery to deliver a child would have been universally fatal to the mother, given the state of medicine in Roman times, so we can be fairly sure that Aurelia bore Caesar naturally.

The origin of the term is uncertain. The technique was known to the ancients, but the actual term first appears only in 1530, and wasn’t used in Roman times.

One theory is that it derives from the Latin caesus, past participle of caedere, meaning “to cut”. This means the section and the ruler derive their names from the same root.

Another possible explanation is that abdominal delivery of babies was mandated in Roman law in the case of a mother who was dead or dying, so as to preserve the child for the state in order to increase the population.

According to this theory, Roman law, once known as lex regia, may have become known as lex caesarica, whence we have the term “caesarian section”.

A similar injunction operated during the early and mediaeval Christian era, when the Church encouraged the delivery of unborn infants in dead or dying women by caesarian section. This would permit baptism, enabling the souls of these babies to be saved.

Whatever the ancient history, the first report of a caesarian section performed on a living woman who survived the operation occurred in 1500, when a Swiss sow gelder, Jacob Nufer, who had some grasp of anatomy, performed the operation on his wife. The incident was only recorded in 1582, however, five years after the baby that was delivered died and 82 years after the fact, so its veracity must remain in some doubt.

In the ensuing centuries, few reports of caesarian sections in which the baby survived exist, and even fewer reports claim that the mother survived. If blood loss didn’t get them, infections could.

A rare success can be attributed to the British surgeon James Barlow, who in 1793 delivered a stillbirth by caesarian section from a mother who survived the operation.

It wasn’t until surgeons had mastered anatomy and the advent of sanitary practices in hospitals towards the end of the 19th century that maternal mortality after caesarian sections began to decline from nearly 100%.

So, was Caesar born by caesarian section? Certainly not.

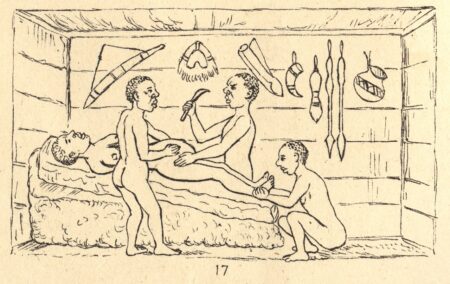

[Illustration:CAPTION: Allegedly successful Caesarean section performed by doctors in Kahura, Uganda, as sketched by R. W. Felkin in 1879 for his article “Notes on Labour in Central Africa”, published in the Edinburgh Medical Journal, volume 20, April 1884, pages 922-930. Public domain. – Caesarian.webp]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend.