You may not be interested in England’s decline as you have your own mentalists – like Herman – to watch out for, but the decline is interested in you – in particular, the things you may have once admired. I’ll preface this with a story about the incumbent Conservative Member of Parliament for Romsey, Caroline Nokes.

One evening in February 2014, police received a frantic 999 call, and the operator immediately dispatched two fast reaction units from one of its Hampshire constabularies to an address belonging to the head of an activist group, Fathers4Justice, who campaign on equal parenting rights relating to divorce law and its consequences. The officers arrived at a bloody scene: a man called Adrian Yalland had entered the property, assaulted Matt O’Connor, chief of the group, and bitten a chunk out of his arm. Curiously there was another witness lurking: an MP called Caroline Nokes.

What was she doing there? According to Mr. O’Connor, he’d been trying to get the MP’s attention for a while – writing, calling, badgering her assistant – and this, of course, annoyed the pants off Ms. Nokes. She’d had it with men: she’d campaigned on old-fashioned, family values aligned to those of her constituents, but once elected in 2010, she’d had a fling – as a great many of her male Tory colleagues are wont to do – with a young male aide, ending her marriage. So, she wasn’t having it. She picked up the muscle, drove to the O’Connor house, unleashed Yalland from the passenger seat, then idled as the lunatic went berserk.

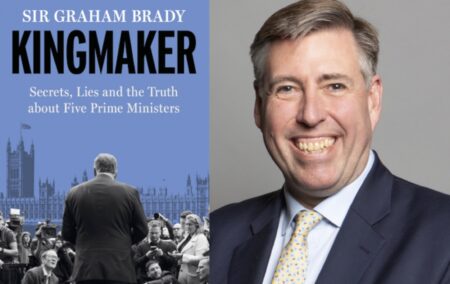

Most influential man

For a decade Sir Graham Brady was the most influential man in British politics you may never have heard of. The Conservative 1922 Committee, which he chaired from 2010, is an organ within the party gifted with the power to break leaders. When complaints about the Prime Minister from his own MPs exceed the threshold of 15% of the parliamentary caucus, it was Sir Graham’s job to begin the retrenchment process.

Before Sir Graham’s time, the 1922 Committee was a special bunch. If a woman called into a radio show and politely suggested a national conversation on equal pay, one of these men would demand she be placed on the terrorism watchlist or subjected to additional checks at the airport. Eventually it was recommended that PR officials who specialised in de-escalation behaviour should accompany some of the more demented of these people wherever they went.

Kingmaker is meant to be about Sir Graham’s time in the company of five Prime Ministers – five in fourteen years – but it’s really a study in fear and squandering, an examination of conflicting ideas and the perils of political bartering. Many people, including myself, are guilty of being seduced by the myth of British exceptionalism – including but not limited to parliamentary civility. Here we have a man once considered “the model of infinite discretion” shattering illusions, effin, blindin, reducing, grassing, and sometimes even moaning.

I’ve met Sir Graham once and he struck me as a nice man – cheerful, well-dressed, impeccably mannered. I couldn’t speak to competence, but it goes without saying that anyone who presides over a clunking rinse cycle of Prime Ministers is either ruthless or useless or…positioned between groups who hate each other, so occasionally side with their opponents.

GNU-esque

Take class. It’s the early 2000s and Tony Blair is Prime Minister. His Minister for State Schools is a man called David Miliband, the son of the Marxist academic Ralph (a china of Joe Slovo’s). Sir Graham approaches Miliband in the chamber with some questions about state school policy, which is important to him as he – unlike the fee-paying Marxist child David – went to one in Manchester. “Don’t mind Graham,” a voice from across the room goes, “he didn’t go to a public (private) school like us.” The voice belongs to one George Osborne, who less than a decade later will be Chancellor of the Exchequer – and one of the most unpopular Conservatives of his generation. Yes, you read this stuff with a smirk: even in the depths of the Zuma catastrophe featuring incongruent trains and milkless dairies, nobody recalls Faith Muthambi and Gwede Mantashe with their fingers in each other’s faces over whether the University of Venda was better than Wits.

What’s happening in the chancellories of power during this era are two things. Firstly, a strategy designed to eliminate opposition in the discussion of identity is covertly underway – revealed only in 2009 when Tony Blair’s speechwriter Andrew Neather confesses: “We aimed to rub the right’s nose in diversity”. Secondly, a man called David Cameron – or Dave – is being primed for leadership of his party and the country, and the tactics he is using are similar to those deployed by Tony Blair, so when the conservatives emerge from 2010’s elections with the most seats, Dave forms a GNU-esque arrangement with another posh boy, Nicholas Clegg, leader of the Liberal Democrats, and a new New Labour government is formed to replace the old New Labour government that the electorate has just voted out.

A parliamentary expense crisis erupts the year Dave assumes office. He’s relatively chilled – he thinks all will be fine the day his MPs “stop cooking their own books, snorting cocaine and sodomising other men”. Clearly the man holds feelings on the subject, and this was captured when I met a gay MP, Sir Chris Bryant in February this year for a tour of Westminster.

He was explaining the origins of the sculptures in New Palace Yard when Dave, then the Foreign Secretary on his way to Israel, walked past us with a smug expression that seemed to say: “Oh, there’s the gay”. “We can’t stand each other,” Sir Chris told me under his breath. His beef stems from a selfie Sir Chris once posted of himself in his white jockeys. ‘Cameron whispered “gaydar” at me in the commons,’ Bryant once lamented – cruel, you would admit, given that Sir Chris’s documented struggle with his sexuality almost led to suicide.

Dave unexpectedly wins a majority in 2015, and the Liberal Democrats scuttle out of the arrangement in poor shape. But their sour departure is not the big story; in the background, an unspoken bargain has been agreed to, and in exchange for their support in those elections, the 1922 has secured a referendum on one of its peeves – the European Union. The following year in June, it is determined that the United Kingdom will leave the EU. Dave is mortified: in spite of the casual homophobia, he’s a Big Europe man – he’s into Big Climate and Big Compliance and all the extensions, such as Big Subsidy. He resigns.

Fridge-freezer

The most apt description I ever heard of Theresa May goes something like this: “She has the wit and charisma of a fridge-freezer that has been faultily connected by a man called Trev”. The party decides she’s the best candidate to front up to some of the slipperiest negotiators in the business – the EU commissars. Predictably she’s outfoxed, as are her woefully inadequate team, but happily the election of Donald Trump in November affords her an important opportunity to frequently hint that, despite her ineptitude, she is far superior to Trump.

The ineptitude gets a bit much, May gets the boot and in steps the jester who many thought – hoped – would be there before her. Boris Johnson is barely three months into Downing Street and Covid makes landfall. He’s sound at first, but then the scientists pull in to frighten the shit out of him. The pre-May chaos, not yet resolved, becomes a shambles; the shambles replaces what once passed for order – and strengthens his new-ish opponent, a man called Keir Starmer, who doesn’t so much believe in democracy as he does in the supremacy of the London left-wing law complex.

In 2022, Johnson is deposed as jesters are: not because of his pandering to G7 leaders in Cornwall in 2022 (“I think we should have a more…a more…a more, erm, ‘gender fluid’ world”), or lying to Parliament, or breaking silly rules (“social distancing”) that should never have existed in the first place, or impregnating almost one-third of the country’s flaxen-haired art gallery assistants. No, he gets fired because he hasn’t responded appropriately when a notorious Conservative spiker-of-drinks, Chris Pincher, feels up a busboy in a member’s club. “Them’s the breaks,” the American-born Johnson laments in his farewell.

Enter Elizabeth “Liz” Truss. Brexiteer, pro-Ukraine, Thatcherite – she’s the woman filmed throwing her arms in the air next to the man wearing red pants when England scores at Twickenham. She hasn’t been Premier for long before the Queen dies and the country retreats into masonic theatre. When it surfaces, she makes a dreadful mistake: pursuing a pro-business agenda, she compiles a radical budget and supply reforms, but in a colossal cock-up, she releases the budget before the reforms, tanking the currency and prompting interference from the Bulgarian head of the International Monetary Fund. Her Chancellor, Kwasi Kwarteng, is tickets. She follows some weeks later.

Now, here appears an opportunity for Sir Graham to reveal that another power centre to rival his own 1922 Committee has emerged within the party – and this structure, this obstacle, is in control. He doesn’t seize it.

The Plot

Who are the folk whispering poison into the inaccessible corridors of supposedly democratically-elected leaders? Who are they ever? I’ve tried to look at this in a few ways. One of them involves another book by another former Conservative MP, more-or-less in Sir Graham’s profile, called Nadine Dorries. The Plot was published last year – and it wasn’t good.

Bless her: she has had some success writing airport romance novels, so she couldn’t help shoehorning some of those loftier devices into a work ostensibly about political intrigue – the result of which reads as if Michael Crichton had asked Hillary Clinton to edit one of his manuscripts, like Congo. Now it’s no longer about an angry monkey, but a woman who, armed with only a spade, prevents a tsunami but isn’t financially rewarded, so is sad. In The Plot, Dorries alludes to this mysterious little clique within the Conservatives. This group has a head, but she doesn’t name him.

I will. He’s Gareth Fox, and he’s rumoured to be the controlling force behind Conservative candidate selection. He is alleged to have scrubbed the internet, spent a night in jail, hosted male orgies. He came in around the modernist ascent (2000s), and supposedly adheres to an ambiguous social justice-y agenda of more women and more people of colour – something that must have conflicted with Sir Graham’s 1922, which must have augmented the existing divisions between the Conservative party “families”. The other way is through a simple question: who really imposed the appointment of Jeremy Hunt as Chancellor the day Truss fired Kwarteng? She almost certainly didn’t.

Then it is the turn of aspiring tech bro Rishi Sunak, a man of mysterious fortune whose father-in-law is known as “The Bill Gates of India”. Sunak and Hunt are a hopeless pair, thin-skinned and better than you, so the country enters an initial phase of clinical depression – more taxes, shots fired at savers, failure to stem the tide of “social justice” effluent swamping corporations via their HR departments and the ending of the non-domicile rule – one of the only things worth living in the UK for.

Sir Graham sees the inevitable: these men are just enabling the transition to Labour, he’s out of puff. There is one sting left and this must hurt: just before the elections this year, his own deputy on the 1922, William Wragg, goes and does a gaydar, sending an unknown man pictures of his privates – and the telephone numbers of his parliamentary colleagues. You see, these are how things end in modern “Conservative” Britain – not with an IED, or a squeal – but with the WhatsApp photo of a photo of a man with poor posture standing in front of the mirror, naked but for his little black socks, followed by the personal contact details of the Secretary for Work and Pensions.

Benefit of the doubt

Give him the benefit of doubt: you can’t exactly say Sir Graham bottled it because there are many – too many – clues lingering between the lines of the events as he remembers them, from where reasonable conclusions are one or two swift calculations away. One of the more obvious conclusions is that men like Sir Graham, and parties like the modern Conservatives – or the Australian Liberals or Canadian Conservatives – are only ever in office, never in power. That belongs to the Blairs, Trudeaus, Biden’s handlers, and so on.

Another is that it wasn’t a failure to adapt to new rules of the game which landed the party – and by extension the country – in its present decline. A distinctly different game had been conceived. And nobody, least of all Sir Graham and his colleagues, knew how the hell to play it.

Appearing for the first time in the late 1990s and early 2000s, this new game functioned within the safety of ceremony and certain illusions – more civility, tradition, legacy. Sir Graham – a smart man – must have seen this. He does his best to disguise the fear his party must have endured.

You can’t blame them. Tony Blair was – is – one of the most advanced political creatures on the planet. Screaming at the moon with him into Downing Street were other Hell’s Angels temperaments – alcoholics, manic-depressives, head-butters, loan sharks, slum lords – people who would go on record describing terrorism as okay, as David Miliband once did – just as long as the cause meets the ideological threshold. So these guys, who are vindictive, consumed by class madness and obsessed with the politics of humiliation, rocked up, and tore up the old rules. Instead of doing the harder thing: i.e scrapping this new game at any cost, which would have also been the right thing, David Cameron guessed how to play it, partly because of his own admiration for Blair. He got it badly wrong. Sir Graham was left to sieve through the ashes.

There were many Conservative scandals during Sir Graham’s time, but not a single one of these suggests that the Conservatives could match the level of sheer aggro set by Blair. The only thing that comes close happened one evening all the way back in February 2014.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend.