Should you avoid GMOs? Should you limit your egg consumption? Should you drink dairy milk or plant “milks”? Should infants eat peanut-based foods?

What we eat, and what we ought to eat, are uncommonly fertile soil for popular myths. There are good reasons why this is so.

Personal health and its relationship with diet are major sources of anxiety for many people.

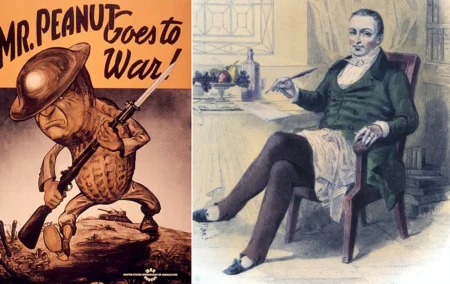

If you are what you eat, to paraphrase an aphorism from The Physiology of Taste, a collection of gastronomic essays by Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin published in 1825, then what to eat seems an important question.

Food is a major industry. On one hand, food producers want to market their products in the best possible light and have a commercial interest in generating fads and fashions. The same is true for authors of diet books, who can earn fortunes from desperate consumers eager for persuasive advice.

On the other hand, consumers mistrust food manufacturers and the profit motive. Many of the reasons for this lack of trust are misguided, but some are very much justified.

Compounding the problem is that diet is notoriously difficult to study.

It isn’t easy to conduct controlled, repeatable experiments on living humans. Diet affects health over long timeframes. We can’t lock up thousands of people for years, strictly controlling everything they eat, every time we want to validate or refute some or other dietary hypothesis.

In pharmaceutical research, scientists study the effects of carefully controlled doses of an isolated substance. Diet is infinitely more complex than that, with more interactions, more complex effects and side-effects, and far less precise dosing.

Not only is a varied diet complex, but many factors other than diet influence health outcomes. These include genetics, environmental exposures, exercise regimes, lifestyle habits, mental health, and medical interventions. Eliminating or controlling for these confounding variables is hard, especially in longer-term observational studies.

Because people aren’t lab rats, and tightly controlled long-term experiments are rarely, if ever, possible, researchers rely heavily on self-reported information. People are notoriously dishonest, however, and often not even wittingly so. As Dr. Gregory House used to say: “Everybody lies.”

In such a contested environment, separating fact from fiction (or rather, plausible claims from improbable ones) is not easy, even for experts who immerse themselves in the subject.

I’ll limit myself, therefore, to myths and misconceptions about which I feel pretty confident and avoid those that are still a matter of disagreement in the dietary science community.

- Young children should not be fed peanut products

File this one under bad advice, since reversed.

In 2000, the American Academy of Pediatrics told parents that children should not be given peanut products until at least the age of three. At the time, about 90% of all food allergy-related fatalities were linked to peanuts and tree nuts (although peanuts are not tree nuts, but legumes like beans, chickpeas, and lentils).

In the decade after that advice was given, the incidence of peanut allergies among children quadrupled. Meanwhile, researchers noticed that the incidence of peanut allergies in the UK (1.85%) was about ten times that in Israel (0.17%). They could not find any explanation other than the fact that Israeli infants were fed peanut-derived foods from a very young age.

It took them until 2017, but eventually, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in the US issued new guidelines: feed children foods containing peanuts early and often, as soon as they begin to eat puréed solids. (Don’t feed them whole peanuts, obviously. They might choke.)

This advice is more broadly applicable: keeping young children away from potential allergens at an early age makes it more likely, not less likely, that they will develop an allergy later in life.

It makes sense: an allergic reaction happens when the immune system mounts an excessive response to an allergen and floods the body with histamines, even though the allergen is not actually dangerous.

Very young children are far less likely than older children and adults to mount an allergic response, so exposing children to potential allergens as young as possible trains their immune systems not to over-react to these otherwise harmless substances.

Children should be exposed to a wide variety of foods and other potential environmental allergens such as cat dander and pollens. The same is true (within reason) about microbes, for that matter.

Keeping children in sterile environments makes them more likely to develop allergies and less able to fight off infections later in life.

2. Plant milk is healthier than dairy milk

Supermarket shelves and coffee shop menus are full of fashionable alternatives to real dairy milk, such as almond milk, soy milk, oat milk, rice milk, nut milk, and other liquids that have no business calling themselves “milk”.

These plant-based “milks” are favoured by vegans, and by people with dairy allergies or lactose intolerance.

Lactose intolerance largely has a genetic basis and is more prevalent in people of Asian and African descent, by comparison with people of European – and particularly northern European – ancestry.

Like allergies, however, food intolerance can also be caused simply by abstaining from certain types of food. As we discussed in connection with gluten, doing so kills off the gut microbes that help digest that food, which makes it harder to digest in future.

That replacing dairy milk with plant milks is good for people who cannot tolerate dairy has created a perception that they’re healthier.

Intolerances themselves are in vogue, marking people as oh-so-sensitive, fragile, and special, so pretending to have intolerances has become fashionable.

Either way, the popularity of plant milk has increased by leaps and bounds.

Plant milks have some benefits over dairy. They have a lesser environmental footprint and are kinder to animals. They also last longer than dairy. But are they healthier?

Plant milks differ. Some are fortified with various nutrients and minerals, in order to improve them as substitutes for dairy. Others contained added salt or sugar, which makes them significantly worse. Very few, if any, can match the nutritional value of dairy milk, however, and most lack important essential nutrients in dairy, such as vitamin D, potassium, and protein.

It is simply not true that they’re healthier, unless you’re among the unfortunates for whom dairy milk is actually unhealthy. If you can drink dairy, it will reliably be better for you than any plant “milk”.

3. Milk increases mucus production

The myth that dairy stimulates mucus production and should therefore be avoided if you’re suffering congestion of the chest or nose, goes back to the 12th-century. It was first advanced by the rabbi, philosopher, and physician Moses ben Maimon, better known as Maimonides.

The belief was reinforced by the very popular Dr. Benjamin Spock, who taught a generation of boomers how best to raise children.

There is a hypothetical mechanism by which this could occur, but there is no scientific evidence that it does. The belief may derive from the texture of dairy when consumed, which may feel like mucus in the mouth and throat.

On the contrary: milk is nutritious, and will benefit someone who is ill, especially if they find it hard to tolerate other food.

4. GMOs are bad for you

Genetically modified organisms (GMOs), by which we generally mean crops into which genes from other species have been inserted to create an improved variety, have been around for many decades.

Invented in the 1970s, the first genetically engineered products were approved in the 1980s, and by the 1990s, genetically modified crops became available for consumption by both livestock and humans.

In that time, study after study after study has concluded that GMOs pose no health risks, and are not inherently less safe than varieties created using more traditional cross-breeding (or even nuclear mutation) techniques. On the contrary: precise gene editing, rather than the scattershot approach of crossbreeding, is much more likely to avoid unwanted characteristics.

There’s a wide discrepancy between the wealth of scientific evidence of their safety, and public perception, however. Public opposition remains strong.

That opposition is based not on rational evidence, however (since there is none). It is based entirely on intuitions and emotions. These include psychological essentialism (that genetic engineering changes the essence of a species), the teleological fallacy (that natural phenomena exist for an intended purpose, or that there is a certain way in which things are supposed to be), the belief that nature is benign (that what is natural is inherently better or safer than synthetic or artificial alternatives), and instinctive disgust.

While all these responses are understandable, they are not based in reality. If GMOs were harmful, we would have seen abundant evidence of it, by now. That people and livestock aren’t showing any ill effects, 30 years later, is strong evidence that GMOs cause no ill effects.

Other concerns about GMOs, such as the involvement of multinational corporations, are not unique to GMOs and apply equally to non-GMO foods.

Notably, organic farming appeals to farmers because organic produce, despite being less efficient and of lower quality, is more expensive, and hence more profitable, than foods grown with the help of modern bio- and agri-technology.

In other words, people who fear GMOs are suckers, and they’re being exploited by greedy capitalists who put profit before people.

5. Eggs should be eaten sparingly

When I grew up in the 1970s and 1980s, my mother followed what she believed to be the best scientific dietary advice of the time. That advice included eating no more than two eggs per week.

The rationale made intuitive sense. We knew that high levels of cholesterol in the blood were associated with cardiovascular disease, and we knew that egg yolks contain 185mg of cholesterol each. It stood to reason that consuming cholesterol would raise cholesterol levels in the blood.

Dietary guidelines specified that we weren’t to consume more than 300mg of cholesterol per day, and given a balanced diet, that left space for two eggs per week.

People duly reduced their consumption from well over three eggs per week in the early 1970s to fewer than two by the 1990s.

Yet this is another myth that can be filed under bad advice, since reversed.

In 2018, researchers found that dietary cholesterol has little to no effect on blood cholesterol levels, after all. As a result, there was no association between dietary cholesterol and cardiovascular disease.

The mandarins in charge of dietary guidelines did not just raise the limitation on dietary cholesterol; they removed it altogether. Turns out the real culprit was saturated and trans fats, and eggs contain very little of either.

It is likely that older studies that found an association between eggs and heart health were unable to separate out the foods that are typically eaten alongside eggs, such as ham or bacon, or didn’t control for the way in which eggs were prepared, such as frying versus poaching or boiling.

The saturated fats or trans fats in bacon, or in the butter or oils used to fry eggs, certainly can raise cholesterol levels in the blood, leading to risk of cardiovascular disease, but the eggs themselves were entirely innocent.

Eggs are (as the BBC put it) a contender for being the perfect food. “They’re readily available, easy to cook, affordable and packed with protein.”

To quote the latest research: “It is worth noting that most foods that are rich in cholesterol are also high in saturated fatty acids and thus may increase the risk of [cardiovascular disease] due to the saturated fatty acid content. The exceptions are eggs and shrimp. Considering that eggs are affordable and nutrient-dense food items, containing high-quality protein with minimal saturated fatty acids and are rich in several micronutrients including vitamins and minerals, it would be worthwhile to include eggs in moderation as a part of a healthy eating pattern. This recommendation is particularly relevant when individual’s intakes of nutrients are suboptimal, or with limited income and food access, and to help ensure dietary intake of sufficient nutrients in growing children and older adults.”

The new guideline is to eat an egg a day, on average, but I haven’t been able to find any good reason for this limit, either. I say, if you like them, eat them. And if your diet is constrained by finances, eating lots of eggs can only help.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend.

Image: Left: A World War II-era promotional poster for peanuts. Right: A posthumously-drawn portrait of Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, author of Physiologie du Goût (The Physiology of Taste, 1825).