The first 100 days of the Government of National Unity (GNU) have been good for sentiment, but on the whole fruitless for fundamental policy reform. At this rate, the same 12 million people who were unemployed in 2023 will be unemployed in 2029, doubtless joined by many more. Trade policy reform is a potentially easy win.

The first four months of the GNU has signaled – and this can change, but with each passing day it is more unlikely – that fundamental policy change is not on the new government’s agenda. “Not rocking the boat” appears to be the name of the game, with the GNU seemingly betting on improved sentiments, and the adequate implementation of existing, bad policy, being sufficient to turn South Africa away from the brink and to return the GNU to power in 2029.

I have my doubts about this strategy.

Liberty First

In the days following the formation of the GNU in June 2024, the Free Market Foundation (FMF) published its Liberty First policy reform agenda, showing that the course to economic prosperity is already well-charted. The agenda, like the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom of the World (EFW) annual report that it is based on, is divided into five areas of reform: Freedom to Trade Internationally, Size of Government, Regulation, Legal System and Property Rights, and Sound Money.

Starting this week, the FMF will publish a report weekly on each area of reform.

While it is quite clear to me that the GNU has not been convinced that fundamental policy reform is necessary – the Democratic Alliance, Inkatha Freedom Party, and Freedom Front Plus, with their “sufficient consensus” veto, should know better, but alas – the FMF will continue to encourage government to reconsider the problematic fundamentals of public policy.

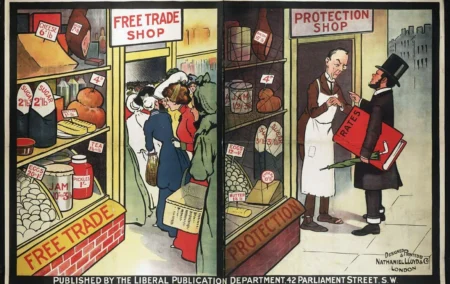

Free trade

But there are also easier options than the fundamentals that the GNU can prioritise, and freedom to trade internationally is one of them. There is no constitutional barrier to immediate trade policy liberalisation.

The first of the FMF’s reports, authored by FMF Deputy Head of Policy, Dr Morné Malan, is on this topic.

Next week, before the medium-term budget policy statement, the FMF is launching its second report, authored by myself, concerning size of government.

“Free trade has been almost universally recognised as the ‘engine of growth’ that propelled today’s advanced economies into their current position of economic flourishing,” writes Malan, but he notes that “recent domestic and geopolitical developments seem to have immunised many politicians and regulators from the effects of such an increased coalescing of professional opinion in this regard.”

Tariffs and subsidies

The core recommendations of the report to improve South Africa’s EFW score on free trade are to revoke tariffs and industrial subsidies adopted during the past parliamentary term, 2019 to 2024; to implement a moratorium on any new tariffs during this term (2024-2029); and to eliminate any other policies that give preference for some traders over others, such as discriminatory licensing and artificial quotas.

Malan writes that the “emphasis on localisation and the comparatively high barriers for new entrants to take part in certain sectors has meant that various firms continue to operate under significantly elevated levels of effective protection both from international as well as domestic competitors.” The result is decreased competition, with incumbents relying on rent-seeking privileges from the state rather than on their own ability to introduce value into the market.

An uncomfortable truth that few people want to hear is that uncompetitive local industries should be allowed to die. I do not think that they will die, because not everyone rushes to buy the cheapest and worst Chinese product available on the market.

But if that is what the market signal is, that is what must happen.

Forcing consumers to purchase specific products because we want to “protect” local industry is perverse, especially given the low levels of disposable income South Africans now have, after decades of anti-growth policy.

If the government is eager to use its violent statist muscles, it must direct them at the source of the problem that it (the government) itself identifies: “slave labour” or subsidies that foreign governments provide to their own industries to make them artificially competitive.

Declare war on those governments, bomb them, or ban officials from those governments from entering South Africa. Do whatever, to those governments.

That makes more moral sense than using the state’s violence against one’s own people, who are peacefully trying to exercise their own judgment as to which products to purchase.

Financial choice

One of the easier aspects of the EFW’s free trade metric to improve is that of financial independence. In this respect South Africa retains many of the bad policies it adopted during the segregation and Apartheid eras to stop wealthy people from taking their own money out of the country.

The FMF proposes that all foreign exchange controls be eliminated.

Moreover, regulations that micromanage how pension fund managers should make investments must also be removed. Pension fund clients appoint the managers, not the government, to exercise judgment according to their own risk and benefit assessments. This is not a matter where government has any role to play outside of prohibiting fraud.

Malan writes that for South Africa “to fully reap the benefits of our financial markets following the May 2024 elections, it must be accepted that the political priorities of an incumbent government should not weigh so heavily as to override the economic and investment calculations of individuals, businesses, and other organisations seeking to find the best destination for their capital.”

Free movement

Finally – and no doubt most contentiously, given the ridiculous contemporary culture war – the report addresses freedom of movement.

South African politicians talk a big game about Pan-Africanism and the important role that BRICS will play in the new “multipolar” world. Let them put our money where their mouths are, and implement immediate visa-free travel into South Africa for all African states and BRICS countries. This should be accompanied by a significant relaxation of work residency requirements.

The silly amount of discretion held by immigration officials (not only in South Africa) must also be curtailed. Just because the rest of the world has abandoned the rule of law in the realm of immigration – “immigration law,” like “tax law,” is in fact a barren wasteland of arbitrary lawlessness – does not mean South Africa, which has dedicated itself to obeying the principles of the rule of law in the Constitution, must follow suit.

Objective criteria and their enforcement must replace the “public interest” sentiments or “good judgment” of immigration officials.

The problem of so-called illegal immigration will be significantly lessened by reducing the barrier to entry, and the widely recognised arbitrariness that goes along with it. This will incentivise people to follow proper customs and immigration channels.

The freedom and agency of the individual – over the unwarranted notion of government expertise – is a clear theme in this and every other Liberty First report published by the FMF. The Cold War ended with the triumph of spontaneous order over central planning, but this victory is being slowly undermined, at the cost of economic growth and prosperity.

Let us insist that the GNU learn from history, follow the charted path to economic freedom, and allow South African society to reap the immense rewards.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend.