Dr Oscar van Heerden is apparently an accomplished academic, although I find his journalistic contributions unimpressive. His regular columns give the impression of having been hastily written and are not always well argued. They do, however, have the virtue of showcasing a consistent worldview. It is geopolitics of Western domination, imperialism, the perfidy and illegitimacy of Israel, the machinations of NATO, and the imperative of the rest of the world to assert itself.

So it was with his News24 column last week, “From Vietnam to Palestine: A history of Western atrocities and agendas”. The title conveys the content well enough. The geopolitical West is culpable of a litany of sins and is backing the genocide being perpetrated by an illegitimate settler-colonial entity. “Help will not come from former brutal colonial powers in the West,” he concludes, “It is up to all of us in the Global South to act, and act decisively and dispassionately.”

This is a well-worn line of analysis, and in essence – if not in such overtly formal expression – closely follows the posture taken by the ANC and the South African state. The important thing to notice is not his rendering of the state of the world, but of his proposed solution. As it happens, Dr Van Heerden was writing as South Africa’s government was preparing for the summit of the BRICS+ group in Kazan in Russia. As the commentary around this event illustrated, it too was widely seen as an expression of the “Global South”.

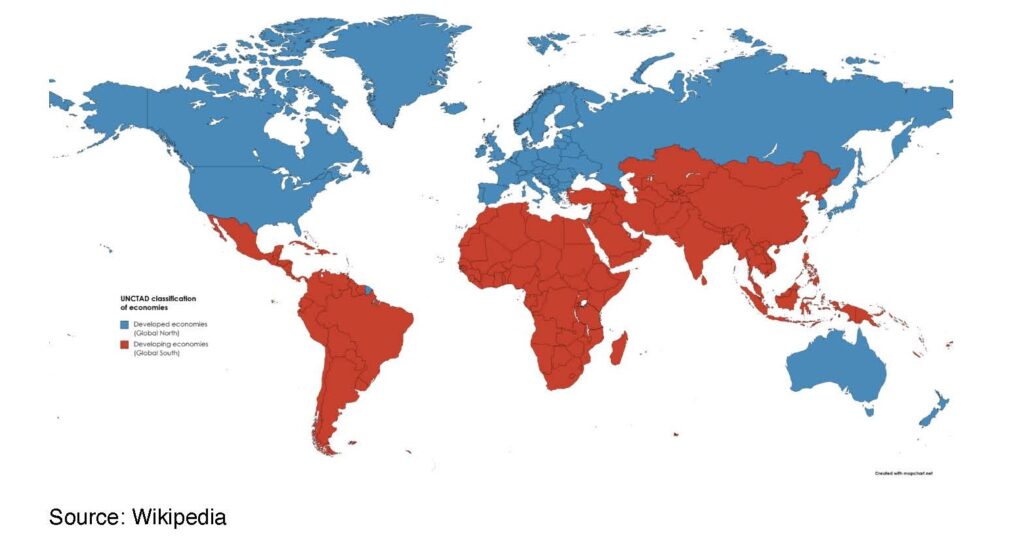

The “Global South” is one of those big conceptual ideas that signify a lot, without providing much by way of a useful or informative definition. In common parlance, it refers to the level of “development”, or as the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) puts it: “North refers to developed economies, South to developing economies.”

From this, we get nice, neat maps that track “developed” largely to the northern hemisphere, and “developing” to the southern hemisphere. Australia, the only inhabited continent situated entirely south of the Equator, is the exception.

But this doesn’t necessarily mean small economies, since China, India and Brazil all feature among the top ten in the world by GDP. In per-capita GDP terms, Singapore and Qatar beat the US, while Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates come in ahead of Japan. Barbados, the Seychelles and Panama have a sizeable lead over Russia. Nor is “developing” or “southern” a reliable measure of living standards, at least not if measured by the UN Human Development Index, which ranks Singapore, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Türkiye and Chile among the “very high”.

The “Global South” as an idea originates in the Cold War era. In the 1950s, the terminology was the “Third World”. This merged politics and economics: the “Third World” countries were neither the capitalist democracies (the “First World”), nor in the Soviet orbit (the “Second World”, a much less-used term), but those whose economies were “underdeveloped”.

This coincided with the independence of Asian and African colonies, and the internationalisation of the movement for decolonising those that remain part of extant empires. The 1955 Afro-Asian Conference in Bandung, Indonesia, brought together leaders of newly independent states which sketched out ideas for a path for decolonisation and disentanglement from confrontations between the great powers. This was followed in 1961 by the formation of the Non-Aligned Movement, the name of which indicated an intention to stand aside from the prevailing geopolitical struggles.

The term “Global South” dates from the 1960s and is credited to an American activist academic, Carl Oglesby, who used it in a critique of the Vietnam War and what it signified for the world and history. His commentary invoked colonialism, the slave trade and so on – phenomena that were invariably described as predominantly Western pathologies. The term had the novel value of casting the “West” – and specifically the US in the current moment – as the prime global malefactor, without entirely excusing the role played by the opposing powers, such as the Soviet Union. (This matter would become important in the late 1970s, when the Soviets invaded Afghanistan, causing enormous blowback in Muslim-majority countries, most of which were part of the “Global South” and for various reasons tended to be lukewarm towards both power blocs.)

Being the global underclass, and being that because of the organisation of the world and the machinations of others, the “Global South” could also be a political signifier. As Dr Sinah Kloß of the Bonn Centre for Dependency and Slavery Studies (which should indicate her orientation) put it: “The concept should not be understood as merely geographical classification of the world, but as a reference attending to unequal global power relations, imperialism, and neo-colonialism.” In her view, the term itself is subversive, calling attention to structural injustice and providing the impetus to oppose it.

This is, one surmises, what Dr Van Heerden has in mind.

There are of course some good reasons to critique the current global order and the conduct of the more influential countries within it. Some deeply doubtful foreign policy choices, such as the 2003 Iraq War, probably did more harm than any good they may have done. Trade relationships are often inequitably structured, as in the case of heavily subsidised “northern” agricultural products that are able to outcompete “southern” alternatives. The use of the Dollar for international transactions between countries of the “South” can push up the costs of trade. The latter is a matter discussed intently at Kazan. These are real issues, and real concerns, where moral and logical arguments may well speak against the conduct of the “North”.

Fundamentally, “northern” countries have their own interests and can be expected to act in terms of them, sometimes in ways that undermine the interests of others. That should hardly be controversial. This is so even as they profess commitments to democracy, to universal human rights and to partnerships with the “South”. As the late Samuel P Huntington wrote: “Double standards in practice are the unavoidable price of universal standards of principle.”

But does the “Global South” offer a better alternative? This is a widely held axiom in a lot of geopolitical thinking, not least in South Africa. And not only in the South African state and the ANC, but among many in civil society and academia who concern themselves with foreign relations. The exact proposals for actualising this vary – multilateral decision-making, reforming global institutions (such as permanent African seats on the UN Security Council), large-scale organisations of “Southern” countries in the mode of Non-Aligned Movement, or groupings of prominent states along the lines of the BRICS+ group.

The BRICS+ option is conceptually interesting: Russia has not typically been regarded as a “Southern” country – although even during the Cold War it sought to position itself as the champion of the “South”, claiming they had a common interest in resisting “imperialism”, which was in turn an exclusively Western impulse. This was taken up enthusiastically by allied groups such as the ANC, and is an inescapable assumption in its foreign policy discussions. China, meanwhile, may long have been regarded as a “Southern” country, but it is increasingly quixotic to make that interpretation now.

Certainly, to regard the world’s second-largest economy as somehow on the global periphery or subject to manipulation by the US and its allies is less and less tenable. And if any notion of non-alignment is invoked, well, China is now an alignment of its own. (Actually, even during the Cold War, this argument was made.)

For the ANC, again, this has been embraced with indecent enthusiasm. As its 2015 party discussion document on foreign affairs stated: “The rise of emerging economies led by China in the world economy has heralded a new dawn of hope for further possibilities of a new world order.” (The same document veered into sycophancy by affirming: “The exemplary role of the collective leadership of the Communist Party of China … should be a guiding lodestar of our own struggle.”)

If economic criteria are to be applied to defining the “Global South”, a large caution must be raised. The countries referred to in this portmanteau concept are a highly diverse group. Even excluding China, there have been some impressive winners: Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia. The case of South Korea after the ravages of the Korean war shows that it is possible to move from utter devastation to “developed” status in a generation. Across the “Global South” there has been an explosion of prosperity, uneven to be sure, but unmistakable (and remember that the development of the “North” also proceeded unevenly). Many others, of course, have not, and Paul Collier’s famous phrase “the bottom billion” calls attention to the human dimensions of this. Still, whether the poverty-stricken of Kivu have common interests with the well-heeled of Kuala Lumpur is a doubtful proposition.

Historical or moral claims are equally unconvincing. If a key indictment of the “North” is “imperialism” – or “colonialism”, as Dr Van Heerden claims – one can equally point fingers at Türkiye, the empire of which was only dissolved a century ago, at the same time as the Austro-Hungarian empire. Much of the Middle East was carved out of its carcass. Modern Istanbul was built on the sacked city of Constantinople, the last remnant of the Roman empire, and the city’s main mosque built on what had been the most important church in the Greek Orthodox faith. The Ottoman Empire engaged in genocide against some of its minorities in the 20th Century, and the conduct of Turkey or Türkiye in the following century, such as towards its Kurish population, has not been exemplary.

Russia itself was an empire, a large, land-based entity that covered both Europe and Asia. China’s origins were similarly imperial in nature, both in subjugating other polities and ethnic, non-Han minorities. China’s conduct in Tibet and Xinjiang, for example, often mirrors the charges made against Israel with regard to the occupation of the West Bank, with the large-scale settlement of Han Chinese, the suppression of local identities and the forcible control of the local population. And China’s historical relationship with its neighbours remains scarred by this history. I wonder how many South African China enthusiasts are even aware of this.

The slave trade, meanwhile, was a lamentable part of human history. Although often held up as a unique indictment of the “North”, the institution has been well-nigh universal across the world and across cultures. There are clear records of slaveholding in ancient Mesopotamia, for example. Certainly, the “North” conducted slave trading – not only across the Atlantic, but within Europe and in the Mediterranean – but so did the “South”. The Ottoman Empire imported slaves of all hues from all points of the compass, and even forcibly took children of subject peoples as a form of tax. There was a long-standing route across the Sahara to bring African captives to the Middle East, while Zanzibar amassed enormous wealth through the trade in slaves and spices between the African mainland and the Persian Gulf. Slaveholding and the trade in slaves were common within Africa. It should also not be forgotten that a relatively small part of the transatlantic slave trade – well below 10% and by some counts less than 5% – went to those parts of the Americas today counted as the “North”. Brazil was the single largest recipient of slaves in the Western Hemisphere, and the institution endured there until 1888. Cuba was another significant destination, although for some reason, neither Brazil nor Cuba seems to be held accountable for this, nor are reparations apparently demanded of either, for this history. (In parts of Africa, slavery persisted as a legal or at least accepted institution into the 21st Century. Mauritania only legally abolished slavery in 1981 and made slaveholding a crime in 2007.)

More pertinently, does the “Global South” have the unity of purpose – and more importantly, the unity of vision and values – to intervene in global crises as Dr Van Heerden hopes?

I doubt it, and this has very little to do with the rights and wrongs of what is taking place in any given crisis. That is because behind the abstraction of the “Global South” are dozens of countries with their own interests – normative and pragmatic – and with highly differentiated capabilities to intervene, as well as varying priorities as to the urgency of doing so.

I’m reminded of an advertisement flighted on SABC when the Non-Aligned Movement was meeting in Durban in 1998. To the strains of determined and inspiring music, the screen flashed words denoting the noblest of impulses: “peace”, “democracy”, “human rights”, while a voiceover intoned the broadcaster’s pride at being associated with the world’s largest “peace movement”. This was ridiculous. The attendees ranged from genuine democracies like India and Mauritius through to absolute tyrannies like Iraq and North Korea. Several of them had unresolved conflicts with their neighbours – while belonging to the same organisation – and were not shy about voicing their grisly intentions for their enemies.

Not a great deal has changed. Different countries have different views on events taking place around the world, and what their posture in it should be. In this sense, countries of the “Global South” are not dissimilar from their counterparts in the “North”, albeit many lack the resources to make their presence felt.

South Africa burst onto the global stage in 1994, promising a new mode of values-driven diplomacy. When the crisis in Zimbabwe blew up, South African pretensions about promoting democracy and humanity blew up with them, as solidarity with a fellow liberation movement took centre stage. (These days, South Africa has declining diplomatic clout, since its poor performance as a country has denuded its national brand of value, and the venality and incompetence of its state have undermined its practical diplomatic capacity.)

Elsewhere things have their own nuances. Several Arab governments are less interested in Israeli transgressions against the Palestinians (a group that serves a useful propaganda purpose, but whose people are often despised) than in the threat from Iran. Iran’s government, for its part, is animated in large measure by a millenarian ideology that is not conducive to peaceful coexistence with anyone who might not share it.

Even the BRICS+ group can hardly offer a coherent geopolitical orientation. As much as South Africa’s government may view itself as a faithful acolyte of China, and as much as Russia has found the Chinese connection indispensable in dealing with the fallout following its invasion of Ukraine, India has a very different view. Sino-Indian relations are a mix of cooperation and conflict, with a disputed border making war between the two a real possibility. It remains to be seen whether a recently announced agreement between the two to deal with these tensions results in any progress, but for the moment, India is keeping its options open. The latter include deepening defence ties with the US and its allies (in the “North” – and also with Australia, which is geographically to the South).

India is not alone in this. There is a strong strain of nationalism and territorial recidivism in modern Chinese thinking which pushes against the interests of its neighbours. Aggressive Chinese claims in the South China Sea have ramped up tensions with Vietnam, the Philippines, Taiwan, Malaysia and Brunei. China is literally building real estate in the ocean within its oddly-named (and even more oddly-demarcated) “Nine Dash Line”. In 2013, the Philippines submitted a dispute with China for arbitration under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. The tribunal found in favour of the Philippines, but China declined to recognise the finding. (Incidentally, the South African government, a vocal proponent of multilateralism and of global institutions, responded to the ruling by asserting that these matters had to be resolved bilaterally. There is a note here of Huntington’s injunction about universal principles and practical hypocrisy.)

For those countries confronted with Chinese maritime policy, a US deterrent in the region has its benefits.

Fun fact: in Vietnam, the “Vietnam War” is termed the “American War”. Vietnam has endured centuries of conflict, of which the US episode was but one, and not necessarily determinative in its current posturing. Its relationship with China has been far longer, more intimate and often more conflictual. In 1979, after the US had departed, Vietnam and China fought a short, bloody war over border disputes, Vietnam’s war with Cambodia – a Chinese ally – and the abuse of ethnic Chinese in Vietnam. For Vietnam, “colonialism”, “aggression” and “hegemony” might more appropriately mean China than the US.

Both China and Russia are known to engage in information and influence warfare – “direct measures” as the erstwhile KGB called it – aimed at the political processes of other countries. The Soviet Union and now Russia was a pioneer in the use of misinformation (even if this has been hyped excessively in certain quarters). China has brought great pressure to bear on its citizens living abroad and even on ethnic Chinese of foreign citizenship to serve the interests of the People’s Republic. It has attempted to interfere in the political processes of countries as diverse as Australia and Zambia. Russia has also taken a very direct role in conflicts beyond its borders as a means of accessing resources and fortifying friendly regimes.

Further afield, a good part of Cuba’s global reputation was built on its willingness to send its military abroad. This included in support of the regime of Mengistu Haile Mariam in Ethiopia – one of the most murderous of the latter part of the 20th Century. This is branded as “internationalism”.

If it is unacceptable when the US or France does it – “neocolonialism” – it’s hard to see why it should be more palatable or differently described when perpetrated by Russia or China or Cuba.

As for Africa, it is also a mixed bag, as is entirely to be expected from a heterogenous continent. Its political systems range from the democratic to the harshly authoritarian. Even the military coup has reappeared, although it is progress to note that the African Union no longer accepts such gun governments, for whatever practical difference that makes. Insurgencies continue in the Sahel region, in Mozambique, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Ethiopia, while Sudan is locked in a civil war. Some evince a respect for human rights and civic freedoms, other evince none (South Africa was the first country in the world to constitutionally protect people on the basis of sexual orientation, something not only illegal in several other countries on the continent, but punishable with death.)

And as far as Israel goes – this being the focus of Dr Van Heerden’s piece, and a preoccupation of the South African government – opinion across the continent is mixed. Israel has had considerable success in forging links across Africa, and it is by no means clear that the current conflict will reverse all of this.

It seems to me that the “Global South” is something of a shibboleth. Not only does it fail as a descriptor of the world as it is, and as it is emerging to be, but also as a geopolitical or ideological idea. As a matter of raw practicality, it is hard to imagine over a hundred different countries with an array of political systems and glorious (or cloying) diversities of geography, ideology and economic interests coming up with a common approach to global problems, let alone a common programme for action.

All that said, the human tragedies that Dr Van Heerden mentions are real; it is hard to argue against the need to find “solutions”. It is by no means clear that these are readily at hand and while he may be correct that “solutions” may not come from the “North”, there is as good as no reason to believe there is any more prospect of them arising in the “Global South”.

The world, in short, may be changing, but it is not obvious to me that all of those engaged in analysing this have understood it correctly.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend.