What follows are my opening remarks at the 45th Hoernlé Memorial Lecture by Advocate Mark Oppenheimer, hosted jointly by the Institute of Race Relations and the Free Speech Union of South Africa at Country Club Johannesburg in Auckland Park on Tuesday evening.*

Ladies and gentlemen, esteemed guests, welcome. And a special welcome to the grandchildren of Alfred and Winifred Hoernlé – we are honoured that you have joined us tonight.

Seventy-nine years ago, a group of liberals gathered to hear Jan Hendrik Hofmeyr deliver the very first Hoernlé Memorial Lecture, much as we are gathered here today.

Our predecessors were interested in the same things as we are today. They wanted to understand what was going on in South Africa.

Through the IRR Hoernlé lectures, the liberal community has been privileged to hear thoughtful assessments from knowledgeable speakers over the past almost 80 years.

Let us take a dive into the past. The range of topics covered by Hoernlé speakers is vast.

In the inaugural Hoernlé lecture, for example, Jan Hofmeyr – at the time IRR vice-president and honorary life member – spoke on the topic of “Christian principles and race problems”.

Other distinguished speakers included:

- Archbishop Denis Hurley on “Apartheid: A crisis of the Christian conscience” (1964)

- Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi on “White and black nationalism, ethnicity and the future of the homelands” (1974)

- Dr Alan Paton on “Towards racial justice: Will there be a change of heart?” (1979) and again on “Federation or desolation” (1985). He was the only speaker to have delivered two Hoernlé lectures.

- Professor Jonathan Jansen on “When does a university cease to exist?” (2005)

- Professor RW Johnson on “The future of the liberal tradition in South Africa” (2011)

Today marks the third Hoernlé lecture I am attending in person.

The two previous lectures I attended left a deep impression.

I heard Otto Count Lambsdorff, a famous German liberal and friend of South Africa’s, warn of the risks of the welfare state in 2006. Speaking from the European experience, he warned that “the growth of social grants [in South Africa] will not come to an end in the foreseeable future”. He quoted the then Minister of Finance, Trevor Manuel, as saying: “Is our vision of a future South Africa one in which over 20 percent of the population depends on welfare for their livelihood?”

Apparently the answer was yes, for today about 50% of households in South Africa receive at least one social grant, and for almost 25% of households social grants are their primary source of income.

In a similar way, many Hoernlé lectures gave their audiences glimpses of the future.

In 2011, at this very venue, I heard Professor RW Johnson speak on “The Future of the Liberal Tradition in South Africa”. I learned that liberalism has much deeper roots in South Africa than I had known.

The following observation by Professor Johnson has always stuck with me: “[…] South Africans — of all races — have long ago crossed the frontier into what one might call a liberal way of life. Even the most loyal ANC activists assume they live in a country where consumer sovereignty prevails, where people are free to say what they want, move where they wish, practise the religion of their choice, read or watch the media of their choice and decide their own family size. […] These freedoms are very deeply ingrained into the everyday life and thought of all South Africans and they are simply not negotiable. […] This is something which ought to give one enormous confidence in the future.”

Liberals have often had a tough stand in South Africa. Many of the Hoernlé lectures convey a sense of anguish about the intractability of the country’s problems and the intransigence of those in charge. To read the historical Hoernlé lectures is to absorb a strong sense of the times in which they were delivered.

I encourage you to visit the IRR website and look them up in their own dedicated section under the “About Us” menu.

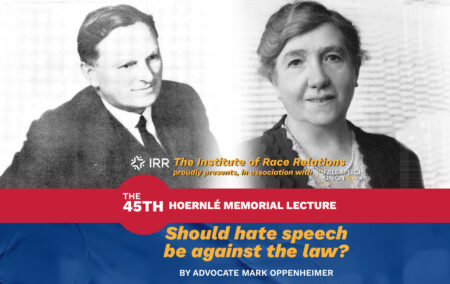

Who were Alfred and Winifred Hoernlé?

Professor Alfred Hoernlé shaped the Institute in his capacity as Council president from 1933 until his death in 1943. His wife, Dr Winifred Hoernlé, was president from 1948 to 1950 and vice president for many years more. They both made an enormous contribution to the Institute.

From the biographies and obituaries I have read, they come across as exceptionally kind and warm-hearted people. They left a lasting impression on those who met them and it is not surprising that the Institute decided to establish a series of lectures in their honour.

The Hoernlés were a genuinely impressive couple, each in their own right.

The Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy calls Reinhold Frederick Alfred Hoernlé, to give him his full name, “perhaps the best known of South African philosophers” and writes: “Hoernlé’s most significant contribution […] was in the application of liberal political thought to the multiethnic environment of South Africa.”

AlfredHoernlé became associated with the IRR in 1932 and served its president for nine years. He was born in Bonn, Germany, in 1880, but spent his early childhood in Calcutta, where he became fluent in Hindi before returning to Germany with his parents.

His schooling was German, but his university studies were English.

He attended Oxford, graduating in 1905. His academic career took him to the University of St Andrew’s (1905-1908), the South African College (now the University of Cape Town) (1908-1912), Armstrong College (now King’s College) at Newcastle-on-Tyne (1912-1914), Harvard University (1914-1920), Newcastle again (1920-1923), before becoming professor of philosophy at the University of the Witwatersrand (1923-1943).

In his introduction to the inaugural Hoernlé Lecture in 1945, IRR director JD Rheinallt Jones wrote:

“In Hoernlé were combined several outstanding qualities. Gifted with a brilliant analytical mind, he was able to trace more clearly than anyone the single threads in the tangled skein of our racial situations. At the same time, his aptitude for administrative work made him ever willing to tackle practical problems, whether in academic organisation, in racial situations, or in such specialised activities as the educational work for the Union forces which he initiated during the present war. He was an outstandingly good lecturer and public speaker.

As a philosophical thinker his reputation stood high in Europe and America, and there is no doubt that his deep concern for the future of the Union and the welfare of its under-privileged people led him to turn aside from an even more distinguished career as a philosopher.”

Alfred Hoernlé applied hard thinking and common-sense practicality towards achieving the goals of the IRR. His approach reflected a rare combination of the scientific spirit and humane sympathy that inspired others to see the purpose of the IRR placed made real: “to work for peace, goodwill, and practical co-operation between the races”.

His wife, Dr Agnes Winifred Hoernlé (née Tucker) was a South African anthropologist, widely recognised as the “mother of social anthropology in South Africa”.

She served as president of the IRR from 1948 to 1950 and as vice-president for many more years.

In an appreciation written in 1960, Gluckman and Schapera wrote: “Mrs. Hoernlé was a brilliant, inspiring, and warm-hearted teacher, who not only excited in her students an enthusiasm for the subject, but developed close affectionate ties with them.”

Dr Hoernlé was born in 1885 in Kimberley, in the Cape Colony; but she moved with her family first to Johannesburg, then to East London at the outbreak of the Boer War, before matriculating at the Wesleyan High School in Grahamstown in 1902.

After earning an undergraduate degree in philosophy, classics and French from the South African College (now the University of Cape Town) in 1906, she studied anthropology at Newnham College, Cambridge, and attended courses at Leipzig University, the University of Bonn, and the Sorbonne.

Professor Loveday, who held the Chair of Philosophy at the South African College, later wrote of her: “She showed a combination of critical and constructive powers unusual at her age. […] I can say without hesitation that of all the students in Philosophy whom I have anywhere taught, she was by far the most capable.”

Upon her return to South Africa in 1912, she undertook field research among the Nama, a Khoikhoi group, in the Cape Colony and South West Africa. She married Alfred Hoernlé in 1914 and they moved to the United States, where her husband taught at Harvard University. Their only child, Alwin, named after them both, was born in 1915.

In 1920, they returned to South Africa, where she partnered with Alfred Radcliffe-Brown, an English social anthropologist, to establish social anthropology as an academic discipline. In 1923, she became the first lecturer in social anthropology at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits). She trained many of the leading South African anthropologists of her era and laid the foundations for the development of social anthropology in the country.

She retired from teaching 1937 and spent the rest of her life focusing on social reforms. She received numerous accolades for her academic and social work, including an honorary doctorate of law conferred by Wits in 1949.

She opposed apartheid, arguing in reports to the government that all cultures composing South Africa’s society had intrinsic value and that no race was superior. She advocated for liberal values such as equal opportunity regardless of race, freedom of expression and the rule of law. As she wrote in an editorial in 1950, “Never resting, never tiring, it is the duty of liberals to devote their initiative and their energy to the achievement of ‘free minds in free societies’.”

All of this is to set the scene for this evening’s 45th Hoernlé Memorial Lecture. We are honoured indeed to welcome Advocate Mark Oppenheimer as our speaker tonight.

Mark is the IRR Council president. He is a practicing advocate and member of the Johannesburg Bar. He has appeared in the Supreme Court of Appeal and the Constitutional Court in a series of cases that seek to determine the boundary between freedom of expression and genuine hate speech.

He is frequently a guest on South African television to discuss human rights and the rule of law. He co-hosts the popular philosophy podcast Brain in a Vat and was recently elected as a member of the UCT Council.

Tonight, he will share his thoughts on the challenging intersection of free speech and hate speech.

Hate speech has become increasingly prevalent, fuelled by social media, political polarisation, and the rise of extremist groups. It can have a profoundly negative impact on individuals and communities, causing harm, inciting violence, and perpetuating discrimination. However, hate speech is notoriously difficult to define and regulate.

Mark will discuss real-life court cases involving offensive flags, demands for an end to gay marriage, and songs calling for the slaughter of ethnic minorities. Along the way he will uncover the value of freedom of expression and determine whether it should ever be limited.

*Advocate Mark Oppenheimer’s 45th Hoernlé Memorial Lecture will be published on the IRR website.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend