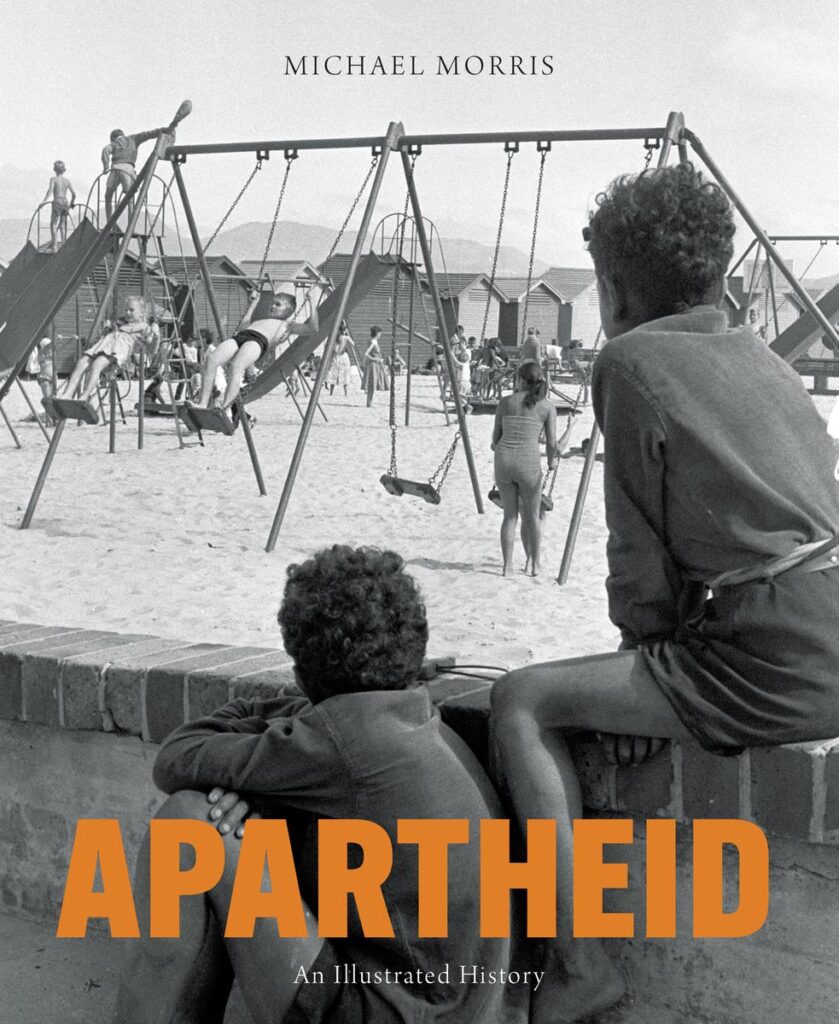

At first glance, the watchers in the photograph are rather like us; outsiders looking in.

Even without being able to see their faces, we can surmise from the boys’ posture something of their wistful curiosity, and the intensity of a gaze that draws our eyes, too, to the central tableau, the larger uncomplicated subject, the ordinariness of holiday leisure in the sun for the lucky permitted few.

But we have the advantage of seeing more than the boys do. We can see that, despite appearances – and, conceivably, despite how they saw it – these two seemingly non-belonging children filling the foreground are also, unmistakably, participants, essential figures of the whole, insiders in fact. It is the failed attempt at excluding them that is so much more obviously aberrant, the non-normal, the deviation from the longer history of shared things.

This beach-side playground would almost certainly have been racially classified under the Separate Amenities Act of 1953, arguably one of the merely “petty” aspects of a system that would eventually become as brutish and criminal as its most rational critics predicted it would. For all its supposed pettiness, it is worth remembering that this Act provided for racially segregating all public premises, vehicles and services – with the sole exception of public roads and streets.

That tells you something about the barren political imagination of its authors. It also tells you how poorly they understood their own society, their own history, even their own destiny.

If race law defined that brick wall in the picture as the absolute limit of permissible proximity for apartheid’s racial outsiders, history would prove defiantly indifferent to it. Nothing under the sun could render apartheid’s subjects as anything remotely like outsiders.

* * *

Beyond the ordinary reasons for being gratified at the appearance earlier this year of a third edition of my 2012 book, Apartheid, An Illustrated History*, the subtle explanatory power of its new cover photograph – the picture discussed in the preceding paragraphs − is the first of two others that stand out.

*Published by Jonathan Ball Publishers

As I suggest above, this image expresses a larger – and more lasting – truth than may at first seem obvious. (Without anyone having thought of it in these terms or planned it on these grounds, I happen to think much the same can be said of the cover image of the first two editions. I’ll get to that later.)

The second reason for some gratification was that, in preparing to update the Postscript – to take in, among other things, state capture, corruption and failures of governance, their consequences for the lived experience of South Africans still, by and large, awaiting the promised “better life for all”, and for the electoral fortunes of the ruling party since 1994 – the final lines, perhaps the key sense-making element of the book, remained as valid today as they seemed when I wrote them in 2011. (Perhaps, more accurately speaking, it was publishing director Annie Olivier’s conviction that, these dozen years later, the final lines of the marginally updated 3rd edition required nil amendment.)

These final lines are framed by a now century-old insight by Olive Schreiner that “(wherever) a Dutchman, an Englishman, a Jew, and a native are superimposed, there is that common South African condition through which no dividing line can be drawn”.

In her introduction to Thoughts on South Africa (published in 1923), Schreiner wrote of this common condition: “South African unity is not the dream of the visionary; it is not even the forecast of genius … (but) a condition the practical necessity for which is daily and hourly forced upon us by the common needs of life: it is the one possible condition which will enable us to solve our internal difficulties: it is the one path open to us.”

In 2011, I concluded my Postscript by noting Schreiner’s prediction that at least a century of labour by “great men” would be necessary to achieve ‘this unity which must precede the production of anything great and beautiful by our people as a whole’.

I went on:

A century might have been enough had it not been for apartheid and all it bequeathed…

Yet, for all that, Schreiner’s vision – and indeed, the vision of, among others, Luthuli, Paton, Mandela and Mbeki – of a people welded by circumstance and need, interdependent and indivisible, is every day affirmed. The notable thing about the apartheid catastrophe is that, for all the depth of its impact and the reach of its legacy, it failed. Being a South African is more than a geographical concept or an administrative classification to determine which queue to join at foreign airports. If it is far from being a settled identity, it is an identity bound up in the continuing argument about belonging. The argument persists, for the sense of belonging persists too. It is certainly not the same as unity, or a common vision, or, even less, mutual affection. But it does suggest that apartheid came and went because its divisions and divisiveness were disarmed, ultimately, by a much longer history of inseparability.

I think if I were asked to underline any portion of this short excerpt, it would be these two lines: “If it is far from being a settled identity, it is an identity bound up in the continuing argument about belonging. The argument persists, for the sense of belonging persists too.”

Perhaps I would add the next one, too: “It is certainly not the same as unity, or a common vision, or, even less, mutual affection.”

Even in 2024, there’s a risk of over-investing in warm-hearted sentiment about what makes South Africans a common nation. Tough though it may be to admit it, one of the things that binds us, if we’re honest, is the sum of memories that rise to the surface every now and then of just how much there is to be bitter about.

The historian C W de Kiewiet reminds us of how some of the earliest conflicts arose over the basic needs of water and grass … “the first principle in the life of Boer and Bantu, for it was in their herds that both counted their wealth”. In the competition for these resources, “(e)very blow that struck at native life had its repercussion on the white community as well. This is the deepest truth in all South African history.”

* * *

But neither the record of abuse nor the resentments it has fostered validate what is often taken as an assumption of irreconcilability, or as proof of a society forced into trying to get along but never really succeeding and never really wanting to, either.

Success often tends to be considered miraculous.

Earlier this year, commentator Carol Paton wondered: “For a while, back in 1994, we were an exception. Can we do it again?” The country’s “chance for a reset” meant that “(we) need our leaders to be exceptional again for our sake”.

Against a hasty but not inaccurate sketch – “in this context of 300 years of violent dispossession followed by 30 years of majoritarian rule by the formerly oppressed that SA finds itself today attempting to negotiate a new truce among free people, among whom are the formerly oppressed and the former oppressor” – Paton looked beyond the immediate question of “who gets what in the cabinet”, noting: “In the longer term, the stakes are higher: it is about starting a new chapter in our history where no party will rule alone, but must seek out co-operation. Culturally, it is a big ask that two such different entities be called upon to govern together.”

She concluded: “With faith, we must hope that it is possible and that SA will again be exceptional.”

And, no doubt, this was – is − true as it goes. Yet, despite the pig-headed nationalism of the past (or, these days, its diehard remnants on the joyless fringe), getting along, cohering after a fashion, sustaining an economy, working together, and increasingly (despite the socio-economic obstacles and impediments of the past three decades) living together − is actually the unexceptional condition.

It’s not mutual affection, and doesn’t have to be. For millions, conceivably, it’s not even familiarity. But there is a unity of purpose of sorts; whether we like it not, choose it or not, no part can go it alone. In fact, I think it might even go beyond that.

Just last week, IRR chief executive John Endres drew attention to the following salutary observation by R W Johnson in his Hoernlé lecture of 2011, “The future of the liberal tradition in South Africa”:

“[…] South Africans — of all races — have long ago crossed the frontier into what one might call a liberal way of life. Even the most loyal ANC activists assume they live in a country where consumer sovereignty prevails, where people are free to say what they want, move where they wish, practise the religion of their choice, read or watch the media of their choice and decide their own family size. […] These freedoms are very deeply ingrained into the everyday life and thought of all South Africans and they are simply not negotiable. […] This is something which ought to give one enormous confidence in the future.”

* * *

The last chapter of my apartheid book opens with an account of a cartoon from the 1980s featuring two men in tropical gear, each with a rifle slung over his shoulder, occupying a raised palisade, a laager of sorts formed by pointed stakes, which is densely surrounded by thousands of black stick figures.

The two men in the solitary fort are evidently oblivious of their jeopardy, for one of them asks the besiegers through a megaphone: “When are you going to realise the hopelessness of your situation?”

“The beleaguered condition, the delusion of power, the defiance of historical forces, never mind the sheer force of numbers – all this was true of the embattled Nationalist government of the second half of the 1980s.

Yet – though it would have been unfashionable, and certainly controversial, to have suggested as much at the time – the cartoon worked both ways.

Writing not many years later, historian Nigel Worden put it crisply when he noted that ‘the state had lost the initiative but no one else had the power to seize it’.“

Neither side could call on more than a fraction of its people to mount anything like the decisive battle that would have been required had the proposition ever really been a military one. The stalemate was arguably less a condition of conflictual exhaustion than a reflection of a flagging conviction in fighting at all. People simply wanted something else; they were clever enough to know that war was the dumb option. They wanted a country to live in, which they could call their country, and they knew that would mean sharing it with everyone else who thought the same.

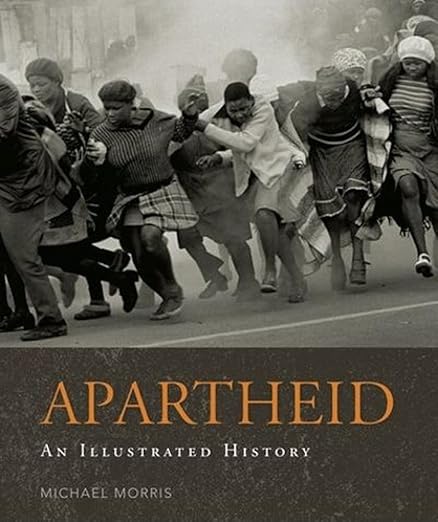

Which reminds me of why the original cover photograph of Apartheid, An Illustrated History is as significant as the new one.

It is actually a famous photograph, taken on 1 August 1977 by a greatly respected former colleague (though a full two years before I’d even stepped foot in a newsroom).

This image won Les Hammond the 1978 World Press Photo of the Year award, one of the most prestigious and coveted awards in photojournalism.

[Image: Koen Suyk / Anefo – Nationaal Archief, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=43239133]

It is quite remarkable, looking at this photograph from a time that ranks as one of apartheid’s darkest periods – it was taken about month before Steve Biko was fatally assaulted by the dutiful servants of what used to be called “law and order” – and seeing this plain truth, that it shows not radical belligerents hellbent on anarchy, not agents of barbarism and mayhem, but women, chiefly, “residents of the Modderdam squatter camp (who had been) protesting against the demolition of their homes outside Cape Town”, fleeing after being tear-gassed by police.

Hammond’s picture brings to mind the late John Kane-Berman’s penetrating analysis of the real 20th century revolution in South Africa in his 1988 book SA’s Silent Revolution, in which he contrasts, for instance, the “2- to 3-million forced removals” under apartheid with the just over 17-million arrests under the pass laws between 1916 and 1981.

Responding to economic needs and opportunities, Kane-Berman writes, “Africans … were simply voting against these laws with their feet”.

Some, back in 1977, really did think the desire of black people to live in Cape Town was a threatening departure from the orderliness, and the “safety”, the dependable norm, of a racially engineered society.

But the truth is that, then, like now, the notion of a South African community that could not possibly include any and every kind of South African was nothing more than a tormenting myth.

[Image: A bronze of Olive Schreiner, featured in ‘Long March to Freedom’, a monument to 300 influential figures in South Africa’s journey to democracy https://www.flickr.com/photos/jaygalvin/48881918598]

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend