An unpopular one-term US president managed to convince a significant majority of voters to give him another chance. What can we learn?

There’s a lot to be said about the thumping the Democratic Party received at the hands of the Republicans, led by their presidential candidate, Donald Trump. Not all of it will fit in this column, but let’s start with a look at what happened, and why.

I wrote a series of columns about the policies of both candidates and the impact that they might have on the US, South Africa, and the world in general. I don’t think any of the arguments I made were wrong.

The first thing we can learn from this election, however, is that none of those arguments mattered.

Short memories

Voters’ memories are very short. In January 2021, as Donald Trump left the White House, having been defeated by Joe Biden after only a single term, his approval rating was low.

On average, throughout his term, Trump managed a mere 41% approval rating. That is four points lower than any other president since Gallup polling started with Harry Truman in 1945.

He left office on 34%, the lowest approval rating of his entire term. This has few precedents in the modern era, with only Harry Truman, Richard Nixon, Jimmy Carter, and both presidents Bush having plumbed lower depths of disapproval at or near the ends of their terms.

Unlike any other post-war president Trump never managed to raise his approval level above 50% – not even in his first 100 days, which even Biden managed.

Clearly, American voters do not remember what they thought about Donald Trump the last time he was president. They gave his return to the Oval Office resounding approval this week.

Inflation

What they do recall is disapproving of Joe Biden. His approval rating was also very low, although the historical context explains why.

A week ago, I went into some detail to make the case that the US economy was actually doing very well, thank you very much. That remains true. It is doing very well.

Most Americans didn’t experience it that way, however, for one very simple reason: they saw grocery and fuel prices go up substantially during Biden’s term, and their wages didn’t keep up with price inflation.

You can explain that inflation was caused in large part by supply chain interruptions during the Covid-19 pandemic, and that this couldn’t reasonably be laid at Biden’s door.

You can explain that pandemic stimulus designed to avoid a recession did make inflation worse, but that Donald Trump started it with the humongous $2.2 trillion Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act in March 2020, followed by the $900 billion Consolidated Appropriations Act in December of the same year. Under Trump, the Federal Reserve also instituted many programmes to support market liquidity and prevent a corporate debt crisis.

In fact, monetary expansion (the increase in the base money supply) amounted to $1.8 trillion under Trump, while under Biden it increased by only $1.2 trillion in 2021, before declining again and ending his term a mere $340 billion higher than where the Trump era left it.

In the last year of Trump’s term, however, the world was still pretty much locked down, dampening both economic activity and inflation. It started to recover when Biden took over, and inflation started to rise precipitously, not only in the US, but also around the world.

As a consequence, Biden was accused of worsening inflation with his stimulus spending, but Trump never was, even though he merited at least half the blame.

Incumbents get blamed

Inflation was also brought back down to near the 2% long-term target under Biden, and his economic policies prevented a widely anticipated recession, but by then, the damage had been done.

Voters only saw prices rising. That hit them in their pockets. They looked up at who was in government at the time, saw Biden, and cast blame. That is the risk of incumbency. Incumbents get blamed, whether or not the blame is justified.

In August 2023, a poll by researchers at Quinnipiac University found that 71% of Americans considered the economy to be “not so good” or “poor”, and 51% said it was getting worse.

Yet 60% of respondents also said that their personal financial situation was good.

These can’t both be true. People’s belief about the economy differed from the reality of the economy – which, as we’ve seen, was better than it had ever been.

A poll from earlier in 2023 found that pessimism about the economy was highly partisan: 61% of Republicans said they were financially worse off, compared to 37% of Democrats. This bias reverses under Republican presidents, proving that partisanship strongly affects voters’ perceptions about the economy.

Lesson: voters don’t care about the details of economic policy, and who causes what, with how much delay. They don’t process complexity and nuance. Instead of basing votes on economic reality, they base them on personal experience and simplistic political slogans that serve as explanations.

People experienced a tough recovery from the pandemic shock, with temporary inflation. All they heard on podcasts and Fox News and even the mainstream media was the misleading and hypocritical accusation from the right that it was all Biden’s fault. And that is how they voted.

Immigration

A similar story goes for immigration. As my previous columns pointed out, negative impacts of immigration, legal or otherwise, do not show up in the data.

They don’t show up in crime statistics (on the contrary: undocumented immigrants offend at a lower rate than native-born American citizens), and they don’t show up in unemployment numbers, which reached 3.4%, the lowest level since 1969, in January of 2023, and remains historically low at only 4.1%.

Immigrants aren’t causing a crime wave or stealing jobs in America.

What they heard, however, was a lot of scary rhetoric, much of it exaggerated, misleading or outright false. Right-wing social media and news outlets beat a relentless drum about the “border crisis” (which it isn’t), borders being “open” (which they aren’t), Harris having been the “border czar” (which she wasn’t), Democrats importing illegal immigrants to bolster their support (which they don’t), Haitians eating cats and dogs (which they didn’t), and about various claims that the great replacement was coming for patriotic, hard-working, God-fearing American citizens (which it isn’t).

Facts and elaborate arguments about principles don’t matter when politicians appeal to base emotions and simplistic claims that intuitively resonate with people.

Democratic Party failure

It should have been possible for the Democratic Party to win this election. The person most responsible for their failure to do so is Joe Biden.

At 78 when he entered office, Biden should have been a one-term president. He never pledged to serve only one term, although his succession was a front-of-mind issue when he was elected.

The Democrats shouldn’t even have tried to run him for re-election. His age was showing long before the fateful debate that forced him out of the race.

That he chose to run for re-election reflects badly on his own judgment, but also on the Democratic Party, which couldn’t produce an alternative candidate that was obviously better suited to running against a resurgent Trump.

Biden should never have chosen Kamala Harris as his running mate. Top tip: when someone comes dead last in your primaries, as Harris did before the 2020 election, she’s not going to fire up voters once she gets to run for president four years later.

If the Democrats had run a competitive primary campaign in 2024, they might have discovered a more charismatic and more widely liked candidate for president.

Harris also erred. For some inexplicable reason, she selected as her running mate Tim Walz, in the hope that his bipartisan appeal in his home state would translate to the national stage.

Walz is a governor from the single most reliably Democratic state in the Union, Minnesota. It is the only state never to have voted for Ronald Reagan, and has been solid blue since 1976. Harris could have picked the devil himself, and still have won Minnesota. Strategically, Walz was a poor choice.

By contrast, Pennsylvania was a key swing state, and happened to have an extremely popular Democratic governor in Josh Shapiro. That choice alone could have made a significant difference in how the election turned out.

There’s a lot more criticism one can levy at the Harris campaign, from their heavy reliance on single-issue voters to their relative complacency about historical, identity-based voting patterns they thought would favour the Democrats.

Reality check

The 2024 election was a reality check for observers, both inside and outside the US. It should be even more of a reality check for the Democratic Party. Until the Republican Party can rid itself of the radical populism, authoritarianism, nationalism, and open bigotry of the MAGA movement, it is up to the Democrats to preserve some of the important principles upon which the US was founded, such as the belief that all are born equal and ought to be treated accordingly, that nobody should ever threaten to turn the military against civilians, and that convicted criminals should not serve in high office.

The US election was instructive about how people choose to vote. High-minded debates about grand political and economic principles might have their place, but in the searing light of election day, complexity, nuance, and even truth, go right out the window.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend

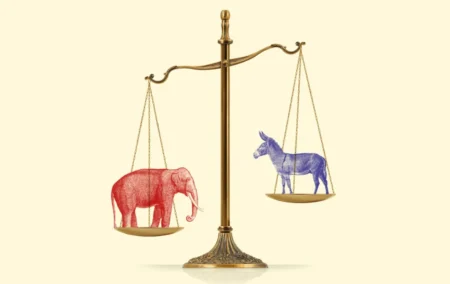

Image: The Democratic Party, represented by a donkey, was weighed and found wanting against the Republican Party, whose mascot is an elephant. URL Media, used under a Creative Commons licence.