“There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.”

These words, in German and in Catalan, appear on a gravestone in the coastal town of Portbou in Catalonia, a small settlement packed into the wedge of a bay that marks Spain’s Mediterranean border with France.

Most immediately, they symbolise a personal tragedy, and a vast infamy. For me, they blink eternally as the amber light at the intersection of all human ideas and actions. Take care, they seem to say; there’s more to this than it may please you to think.

The words belong to the man buried there, the philosopher Walter Benjamin, who, on the night of 25 September 1940, committed suicide at Portbou’s Hotel de Francia by taking an overdose of morphine tablets.

With him in his hotel room was the completed but unpublished essay, Theses on the Philosophy of History, from Section VII of which the words on his gravestone were taken.

The essay is a beguiling blend of figurative and analytical material; then, as now, Section VII has a poignantly prophetic quality.

Having reached Portbou in the last week of September 1940, Benjamin was on the very brim of – only, conceivably, hours away from – liberation and a life without fear of or threat from the catastrophe that was, even then, near at hand.

He had already left Germany, his home, in the late 1930s, but, under the Reich Citizenship Law of 1935, being Jewish meant that he could no longer claim German citizenship. Ironically, as he – seemingly successfully at first – embarked on fleeing the Nazi regime, his status as a stateless person rendered him vulnerable to the gathering force of what historian Max Hastings has described as the greatest human disaster in history.

In France, Benjamin was arrested and detained in a prison camp near Nevers. He managed to secure his release after three months, but, having returned to Paris in 1940, the brisk advance of the Wehrmacht compelled him to move yet again. On 13 June, just one day before German forces entered the French capital, Benjamin and his sister, Dora, fled. It is said there were express instructions to arrest Benjamin at his flat at 10 Rue Dombasle in the 15th Arondissement.

By August, a friend having interceded to secure a visa for him for the United States – the plan was that he’d cross the Atlantic from neutral Portugal − Benjamin had made his way south, to Lourdes, with the idea of crossing into ostensibly neutral Francoist Spain, thence Portugal.

The record shows that on 25 September 1940, Benjamin successfully crossed the French–Spanish border, at Portbou. He must have felt that he was at least well ahead of his intended persecutors. But the barbarism was at his heels.

Having just crossed into Spain, he learned that the Franco government had cancelled all transit visas, ordering the Spanish police to return invalid travellers to France. This included the Jewish refugee group Benjamin had joined, whom the Spanish police told would be deported back to France the next day.

Frantically assessing the risk, Benjamin chose to act. By killing himself, he may in fact have saved the rest of his party; it is thought possible that Benjamin’s suicide so shocked the Spanish officials that they allowed the others in the group to continue unheeded. The party left Portbou a day later, reaching Lisbon – and gaining their first foothold of freedom – on 30 September. (Note: the gravestone referred to above dates to 1979. A second memorial in Portbou, Passages, designed by Israeli artist Dani Karavan, was unveiled in 1994. It bears Benjamin’s statement: “It is harder to honour the memory of the nameless than that of the famous. Historical construction is dedicated to the memory of the nameless.”)

A number of notable literary and intellectual figures were bound up in these events. On his flight from Paris, Benjamin happened to meet up with Arthur Koestler, later famous for his fiercely anti-totalitarian novel Darkness at Noon, who borrowed some of Benjamin’s morphine pills, just in case. Some weeks after Benjamin’s death, Koestler, now holed up in Lisbon, took the pills when it seemed he might not be able to get out of Europe, but he survived. And it was none other than Hannah Arendt − probably best remembered for her account of the early 1960s trial of Adolf Eichman and her conception of the “banality of evil” – who, after crossing the French-Spanish border at Portbou a few months after Benjamin’s party, handed the manuscript of Theses on the Philosophy of History to fellow philosopher Theodor Adorno, thus ensuring its later publication.

A doubly grim footnote records not only that Benjamin’s brother Georg was killed at the Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp in 1942, but that, by a terrible irony, Georg’s widow, Hilde, who became an East German judge and Minister of Justice of the German Democratic Republic, is most notorious for having presided over the East German show trials of the 1950s, which were damningly likened to the Nazi Party’s Volksgericht show trials under the demonic Roland Freisler.

* * *

Why Walter Benjamin, in South Africa, in December 2024?

Improbably, perhaps, I turned to Benjamin in light of the range of contributions to the Daily Friend comments section last week in response to Media Review Network researcher Mariam Jooma Çarikci’s piece, Right of reply: Israel is turning up the smokescreen to obscure the ICC’s warrant for Netanyahu, responding to Marika Sboros’s 9 November piece, Peeling back the curtain.

I took a slightly more than usual interest in what people were saying not only because I had been the one to receive Sboros’s piece and – after having told her we would be happy to use it so long as she was confident of her claims, and could provide links to sources for them – forwarded the slightly revised version to the duty editor that week, but also because, last week, having seen Carikci’s right of reply in Biznews (which had re-used Sboros’s piece), I had immediately got in touch with the Media Review Network to ask if we could run it, too.

Not for a second did I or deputy editor Marius Roodt − who happened to be editor on duty last week, too − doubt any aspect of these arrangements, or the importance of using Carikci’s response without alteration.

The simple reason for this straightforward procedure is that we are liberals.

My sense is that this is for the most part perfectly understood – even if, quite properly, now and then contested – by our readers. The comments – 228 by yesterday afternoon − reflect by and large our readers’ willingness to engage just as they see fit, as the small, edited selection that follows demonstrates.

One, for example, wrote:

“The Daily Friend has lost my respect for printing this article. It has tarnished its own reputation.”

But another pointed out:

“TDF is a liberal website that somehow attracts an ultra-right, openly racist and pro-apartheid comments section. I think it’s due to the fact that TDF, being impeccably liberal, tends to favour near-absolute free speech as opposed to banning people or comments.”

Should “hate speech” qualify, one unsettled reader wondered:

“Wow. When did the daily friend start allowing commentators to publish hate speech”

Another felt the writer (Çarikci) had chosen the wrong site entirely:

“Perhaps you’ll have more luck finding people that share your viewpoint over at Daily Maverick – they all just love that kind of cr@p there”

To which idea another in turn responded:

“Yeah, that’s the solution, we all stop any debate, we stop considering counter-arguments from people with other views and so on, all in the interest of defending the indefensible, i.e. that every civilian, woman, child, elderly, newborn, mentally handicapped or similar person had that bomb or bullet coming, and that this is 100% justified, legally, morally and ethically. What a glorious echo-chamber it would be here on TDF. Upvotes all round, much back-slapping and warm hand-shakes.”

Or is the Daily Friend community, in fact, just another wretched echo chamber, as one reader suggested?

“Yes, this place is a racist echo chamber. It’s such an irony how they call themselves the Institute for Race Relations and say they stand for liberal democracy but almost to a man they stand up for the racist Apartheid state of Israel while it conducts ethnic cleansing and genocide.”

The first sentence of this last comment (also highlighted in the second selected comment, above) does signal a risk we face, as liberals − probably best described as a risk of contamination − in giving a platform to illiberal ideas we reject or individuals whose company we would not keep.

Why, then, should we tolerate them?

Even where openly reactionary readers set our teeth on edge, we believe very strongly in trusting our audience – you, and the next person, reading this – to judge for themselves, and we are confident in entrusting you, our audience, with the task. It is not an absolutist position; we do signal where we stand, sometimes even, if rarely, by censoring comments we are not prepared to lend our platform to. Even in the case of these rare exceptions, the gist of one or another unpalatable comment, couched differently, could very well pass muster; we strive to keep the region of permissibility wide. After all, liberals tolerate ideas not because we agree with them, but because they have been expressed, will likely move people, and must be weighed and engaged head on. The alternative is delusion and narrow-mindedness.

As one reader remarked in the comments thread:

“I have no problem with Daily Friend publishing such writers, free speech is free speech; something very missing in the countries the author is promoting; Iran and Hamas controlled territories. Speak out there and you will be lucky to be beaten to death.”

And, on a similar theme, another observed:

“Finally, I will say that I think it is a good thing that Daily Friend publishes you, which is more than might be said for any opposition voices in any part of Palestine.”

These are just some of the comments in a conversation, a vigorous contest of ideas, that I recommend, if you have not already read it.

* * *

In sum, there is no geopolitical or strategic disposition that overrides the essential liberal preoccupation – which is, ultimately, that doing the thing, is the thing itself; there is no end that can be justified if it differs from the means adopted to achieve it. Muscular – real – liberalism is an everyday affair sustained by a habit of fearless thinking. It is the means and the end, and the founding meaning of freedom.

It is the willingness – if not always the ability – to level with the implications of Benjamin’s demanding conception that “there is no document of civilisation which is not at the same time a document of barbarism”; it is to have the good sense never to hesitate in putting the testing question, “Is this or that conduct civilised or barbaric?”, or having the courage to ask, “Is what I am doing, believing I am right, civilised or barbaric?”

And, not to put too fine a point on it, no side in any human conflict can ever be relieved of the discomfort of submitting to these tests, or can claim a pass for good conduct in advance.

* * *

One question remains: How can we tell civilisation from barbarism?

Not easily, is almost certainly the best answer and perhaps the only one. And nor should we want it to be any different.

If civilisation means anything, perhaps it is the habit of fearless contemplation, of being willing to consider every idea under the sun, knowing that the alternative, the stifling certainty of the utterly convinced on the left and on the right − and their willingness to subject all around them to dogma, constraint and the withering intellectual fear of deviating from the approved path under the wayward influence of care, curiosity or delight − is an everyday threat, an hourly risk, to the liberty of individuals, and to the flourishing of human possibility.

Fearless contemplation, let’s be honest, doesn’t guarantee very much. It is seldom convenient, it will likely often be decried as ineffectual and even puny, and its outcomes can never entirely be vouched for.

We have one helluva argument on our hands, people are angry, speaking from the heart and saying the wildest things – what’s the good of that? The answer is that, as long as there’s an argument – rather than the suffocating unanimity of the certain and the convinced − the chances are at least better than nil that we’ll manage to hold barbarism at bay. That may not sound like much, but it is far greater than it seems. It is ultimately the reward of being willing to pause a moment before that amber light blinking eternally at the intersection of all human conduct.

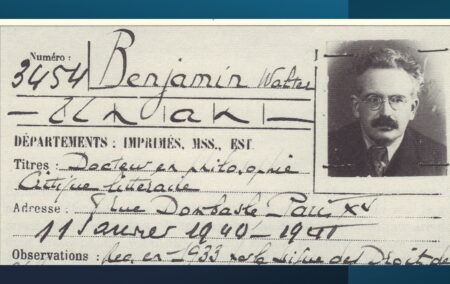

[Image: Walter Benjamin’s membership card for the Bibliothèque nationale de France (1940)]

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend