This is my last column of the year, and since I have nothing interesting to say about the two usual topics at year’s end – what a terrible year it has been and the seasonal slaughter on our roads – I thought I’d indulge myself in questions that have long puzzled me about perhaps the most subversive figure in history.

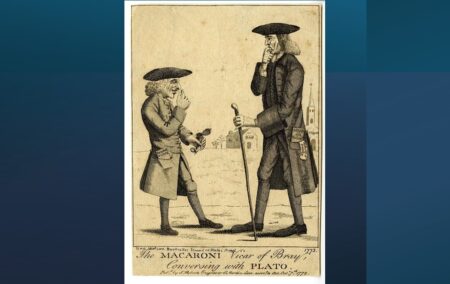

He is a legendary figure, part comical, part outrageous, part cynical, part self-righteous. He is famous not for having wicked principles but for having no principles at all − and being quite unabashed about it. He is a sort of counter-inspiration, dousing all high-minded ideals. He was subversive to all persons of power by subverting none of them. What lessons can we learn from him? I don’t know, and this worries me. His fame comes from a comic song but there is evidence that he was a real historical figure, living in very dangerous times and coping with them most successfully. He is The Vicar of Bray.

Let me first briefly mention the two usual year-end topics. I think 2024 brought more good news than bad. The ANC’s dramatic decline in the May election, losing it the absolute majority it had enjoyed since 1994, was wonderful, breaking up the awful monolith that has damaged our country and especially our poor people so badly over the last 30 years.

Trump’s victory in the USA, despite being massively outspent by the Democrat election machine, despite being condemned by 90% of the big mainstream media, despite the sneers of the rich, woke elite, brings hope that the worries and wishes of ordinary people might at last be listened to.

In Syria the sudden fall of the Assad tyranny in Syria seems likely to do far more good than harm (although I can’t begin to understand the complicated factions in Syria). On our festive-season roads, there has been even more bloodshed than at this time last year. Amidst the usual blather about the reasons for the carnage, I heard one woman, I think a spokesperson for a campaign to end drunken driving, giving the real reason: lack of law enforcement. But back to the Vicar of Bray.

The famous song covers the period in England from 1660 to 1714, from King Charles II to King George I, a period of six monarchs, of whom one was Dutch and one German. These two were chosen not primarily because of their close descent from a previous monarch but also because of their religion (Protestant).

Different religious ideas

All six monarchs had different religious ideas, which were enforced upon the public, with grievous punishments for non-compliance. Bray is a town in Berkshire, with quite a large parish. Any vicar there had to be very careful what religious rituals he observed and what sermons he preached, or else he might lose his job – or his life. The Vicar of Bray dealt with the changing religious fashions in this famous philosophy.

And this is law, I will maintain

Unto my Dying Day, Sir.

That whatsoever King shall reign,

I’ll be the Vicar of Bray, Sir!

Here is a splendidly pompous rendering of the song:

My first reaction to the song was to smile, the obvious response. But what did I think of the vicar himself? I felt uneasy when I realised I admired him. His blatant lack of principles and beliefs should make me despise him but I found it did the opposite. His prime aim was survival at all costs, and he managed to survive rather comfortably, doing whatever his masters required and never believing anything they proclaimed.

His first master, Charles II, was the easiest. Charles had the same religious convictions as himself: none whatsoever. His father, Charles I, had had his head chopped off by Cromwell towards the end of the English Civil War (1642-1650). Cromwell ruled in a republic until his death in 1658. In 1660 Charles II was recalled to become King of England. Charles was crafty, lecherous and a genius at realpolitik. He knew that religious differences – between Catholic and Protestant and between different creeds of Protestantism – could cause conflict. He knew he had to tread carefully, and he was well suited to do so since he didn’t give a row of beans for any religion. In Churchill’s words, “He walked by the easy path of indifference to the uplands of tolerance.” This suited the vicar perfectly since all he had to do was praise “King Charles‘s golden days, when Loyalty no harm meant.”

Unspeakable cruelty

(I must insert a sinister note here. Charles II was usually tolerant and easy, but he did have one early moment of extreme vindictiveness and unspeakable cruelty, which is pertinent to this article. He wanted revenge on the regicides, the men who had tried his father and condemned him to death. If you believe kings are above the law, as Charles I did, then his trial was unconstitutional. If you think that kings rule under solemn contract to serve faithfully their country and their people, then the trial was lawful. It was scrupulously fair, and Charles I was rightly found guilty of treason and condemned to the relatively light punishment of beheading.

His son now demanded revenge on the regicides, some of whom were men of the highest possible moral standing, and one of whom, John Cook, is one of England’s greatest heroes and martyrs. The trial was a farce. Everyone knew the accused were condemned to death before the trial began. Their deaths were by hanging, drawing and quartering. First, they would be hanged by the neck until in a state of agony but not unconsciousness. They would be dropped to the ground. Their penises and testicles would be hacked off and held up in front of them. Then they would be drawn. There were two methods. I’ll only describe the easiest. The victim would be laid down on his back, a butcher’s knife would open up his torso from his throat to his groin, his intestines would be hauled out of his body and, still connected, roasted on a brazier in front of him. I say again, this was the easiest of the two methods of drawing. Then his head would be cut off and his body chopped into four quarters. All of this was done in public, in front of an appreciative crowd. No doubt the Vicar of Bray knew all about it.)

The vicar’s next king was a very different man. Charles II died in 1685, and his brother took over as James II.

Stupid religious fanatic

He was the opposite of Charles, a stupid religious fanatic, and a ferocious Catholic. It was widely perceived and feared that he wanted to restore all England to Catholicism. The vicar hastily made his adjustments.

When royal James usurped the throne, and popery came in fashion,

The penal laws I hooted down, and read the Declaration.

The Church of Rome, I found, did fit

Full well my constitution

And I had been a Jesuit, but for the Revolution.

By the “Revolution” he meant The Glorious Revolution of 1688. Powerful men in England, fearing James would force Catholicism on the whole country, head-hunted for a replacement king, who had to be a Protestant. They chose a Dutchman, William of Orange, and invited him to invade and take over England. He did so. The vicar changed over quickly.

When William was our King declared, to ease the nation’s grievance,

With this new wind about I steered, and swore to him allegiance.

Old principles I did revoke

Set conscience at a distance.

And so on, through the reigns of Queen Anne and then the Hanover (German) Kings George. They came and went, heretics died and martyrs groaned, and the Vicar of Bray kept strolling onward, an unprincipled immortal. He not only changed religious affiliation to suit the times but political as well (the two main parties then were the Whigs and the Tories). Here is the big question: was he right? He never seemed to laugh at any religious belief or stand on any principle; he just disregarded them all, impervious to what people might think of him, bent only on comfortable survival. He made all principles seem silly. Would the world be a better place if everyone was like him – if it were shorn of martyrs and heroes? Some insight comes from searching for the historical Vicar Of Bray.

Fearful century

There were several historical contenders for the real man, including one Simon Aleyn, who died in 1565 and actually was Vicar of St Michael’s Church, Bray. But here is the thing: they were all in the 16th Century, the century before the events of the song. In England, in that fearful century, religious terror and persecution were even worse than in the 17th. Changes in required religious practice were sudden and bewildering, and very dangerous. Behind all this was the horrifying figure of King Henry VIII.

Relief from the madness came late in the century from his wonderful second daughter, Elizabeth. Henry began as a militant Catholic, and was recognised by the Pope as “Defender of the Faith” (against Luther and Protestantism). As a young man he married Catherine of Aragon, who was older than him. She bore him a daughter but after a long marriage no son. He met and became infatuated with Anne Boleyn, who he thought would give him a son. He asked the Pope for permission to divorce Catherine so that he could marry Anne. The Pope refused, not primarily for any religious reason but because Emperor Charles V had political power over the Pope and Catherine was Charles’ nephew. (Politics and not religion played the major part in most of these events and disputes.)

Henry raged, married Anne anyway, and then began breaking away from Rome’s authority. He declared that he was the head of the church in England.

Finally he passed a law saying that anyone who refused to recognise him as the head of the church would be executed. Thomas More and Bishop Fisher refused and had their heads cut off. Gradually most of the English population converted from Catholicism to the Church of England, a rather vague version of Protestantism, which it was a capital offence to resist even if it were ill-defined. How did Henry convert everyone so successfully? By terror.

Treason

In the words of Henry himself, warning everyone not to resist his new religion: “Our pleasure is that dreadful execution be done on a good number of the inhabitants of every town, village and hamlet that has offended in this rebellion.” If the inhabitants resisted him, they were guilty of treason and so would be hanged, drawn and quartered. If they went too far theologically from his moderate Church of England towards, say, Calvinism or some more extreme Protestantism, they were guilty of heresy and would be burnt to death. Every little town had seen dismembered bodies and roasted human flesh and remembered the screams of the dying.

Henry died in 1547 and the crown went to his nine-year-old son, who became Edward VI. Edward was a fanatic Protestant and would likely have inaugurated a Protestant reign of terror had he not died at age 15. His sister, a fanatic Catholic, took over as Queen Mary in 1553, and burnt about 300 Protestants to death, including the reluctant but glorious martyr, Thomas Cranmer. “Bloody Mary”, as she became known, died in 1558 and her young sister, Elizabeth, became England’s wisest of monarchs, who brought some calm, tolerance and good sense – and expediency − to the country’s religious strife.

During all this time of horror and madness and bewilderment, it seems there was a real Vicar of Bray, watching everything carefully from his pulpit, making constant adjustments to his parish, quickly embracing the latest religious fashion and denouncing the previous, knowing when to flatter and whom to flatter, when to condemn and whom to condemn, and surviving, surviving, surviving.

I think he, the man without principles, was just about the wisest man of those dreadful two centuries.

Elizabeth had power and convictions. The vicar had neither but he survived as well as her and built a legend of selfish indifference to stupid ideas. Those religious convictions and differences for which men fought heroically and died in agony now seem to us silly and obscure. How could people get so passionate about whether there should be candles on the altar or not? How could they spend so much time and blood in deciding whether the communion wafer represents the body and blood of Jesus or actually is the body and blood of Jesus? (This is the debate over the transubstantiation, which caused untold conflict.) I am an atheist but nothing in my reading suggests that the Jesus of the Gospels would have cared in the slightest about these matters. So, in this case, I think the vicar was right.

Risk your life

What about other cases? Are there times and occasions when it is sensible to risk your life for a cause? I suppose so, although I cannot think of too many. Most of the time great disputes and conflicts are settled by negotiation and diplomacy. You couldn’t stop Hitler that way; you had to stop him by force, and you had to risk your life doing so, but Hitler’s case was rare. Apartheid ended because of the commercial and social advancement of the Afrikaner ruling class and because of the economic self-destructiveness of the system rather than because of any heroism from the anti-apartheid movement, although there was plenty of that. Now and then the Vicar of Bray is wrong; mainly he is right.

Here are his concluding words when the Hanover kings (German and Protestant) had taken over the British crown.

The illustrious house of Hanover and Protestant succession

To these I do allegiance swear … while they can hold possession.

For in my faith and loyalty

I never more will falter,

And George my lawful king shall be … until the times do alter.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend