Fifty-years ago – 15 days after Richard Nixon resigned the presidency – the Danish freighter Diana Skou slid away from the Brooklyn Army Terminal pier into the East River and set a course for Cape Town 6,800 km away.

The previous night Connecticut friends had come aboard for a festive ‘bon voyage,’ wishing Shel and me well as we set out on an adventure that would take us half way around the world. The next day, steering past the Statue of Liberty and under the Verrazano Bridge into the Atlantic Ocean, I felt strangely uneasy, haunted by the parting words of good friends, “This (adventure) could be very good or very bad.”

We were 31 and 23, newly married. My academic career on hold, for three years we had lived in the back country of Greenwich and Stamford, I doing landscaping, substitute teaching and bar tending while Shel worked as a secretary for an ad agency. All the while I toiled without success on a biography of muckraking journalist Lincoln Steffens.

Far-reaching change

We find ourselves aboard the Diana Skou because I believed far-reaching change was coming to South Africa and my dream was bringing that story to the American public. Our odyssey began a few months earlier on April 25th when young officers in Lisbon refusing to fight Portugal’s colonial wars carried out what became known as the carnation revolution. Overnight this peaceful coup ended four decades of dictatorship. I reasoned that if the vast Portuguese territories of Angola and Mozambique became independent, white rule in southern Africa was doomed.

It’s remarkable how quickly one adapts to the slower rhythm of shipboard life. There’s breakfast at eight, tea or coffee at ten, lunch at noon, coffee at three, and dinner at six. The bar is open 30 minutes before both lunch and dinner. Altogether we are seven passengers, a missionary family of five returning to Zambia, and Shel and me. We dine at the captain’s table along with the chief mate.

Our master is Theo Ejsing, 53, from rural Denmark, currently living with his South American wife in Chile. Karl Johann, a bulky, soft-spoken man, is the chief mate. He says little. They arrive at meals casually dressed and chat amiably in Danish but engage their passengers in fluent English.

It is immediately apparent that my attractive young wife is a centre of attention and envy. We spend our days reading in our spacious cabin, a pleasant breeze coming through an open porthole, or lounging in deck chairs on Monkey Island, the cramped, upper-most part of the ship adjacent to the exhaust funnel. From here we watch the bow create small white waves as the ship slices through a calm sea. Occasionally we watch schools of flying fish darting in and out of the water. For the first few days a forlorn pigeon, a refugee from Brooklyn, stands motionless on a wire next to the funnel.

Routine

It’s remarkable how quickly one adapts to the slower rhythm of shipboard life. There’s breakfast at eight, tea or coffee at ten, lunch at noon, coffee at three, and dinner at six. The bar is open 30 minutes before both lunch and dinner. Altogether we are seven passengers, a missionary family of five returning to Zambia, and Shel and me. We dine at the captain’s table along with the chief mate. Our master is Theo Ejsing, 53, from rural Denmark, currently living with his South American wife in Chile. Karl Johann, a bulky, soft spoken man is the chief mate, says little. They arrive at meals casually dressed and chat amiably in Danish but engage their passengers in fluent English.

It is immediately apparent that my attractive young wife is a center of attention and envy. We spend our days reading in our spacious cabin, a pleasant breeze coming thru an open port hole, or lounging in deck chairs on monkey island, the cramped, upper-most part of the ship adjacent to the exhaust funnel. From here we watch the bow create small white waves as the ship slices through a calm sea. Occasionally we watch schools of flying fish darting in and out of the water. For the first few days a forlorn pigeon, a refugee from Brooklyn, stands motionless on a wire next to the funnel.

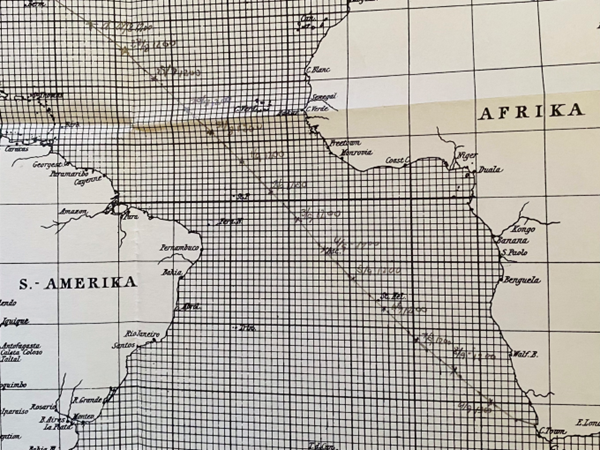

Days are marked by routine. The captain seldom varies from a Martini aperitif before dinner followed by either Dubonnet or Peter Heering as nightcaps. The Fergusons, the missionary family, keep to themselves. They tell us they have been 18 years in a remote part of Zambia 60 miles from the nearest store. Each day at noon the second mate holds a sextant to his eye and charts the ship’s position, which is plotted on a chart (below). Our progress is straight and steady, the sea wide and empty. Only once do we see another ship, a far-away speck crossing our stern.

Midway through the voyage there is mild excitement when an albatross, its great wings extended and only occasionally fluttering, glides majestically riding the heat contrail from the funnel. For centuries a lucky omen to mariners, except for its girth and wingspan the albatross resembles a large sea gull.

It comes as a surprise that there are multiple dining or mess facilities – ours at the top for captain and passengers, another one deck down for officers, and a third below that for the remainder of the crew.

A week away from our destination the Southern Ocean is colder and less hospitable. We peer through binoculars at a distant speck of land on the port side. It is St. Helena, a remote windswept British island where the defeated Napoleon was imprisoned.

Ship of fools

Inevitably on a voyage of long duration there is recognition – willing or not – that all of us are participants in a play, a ship of fools. Collectively we number 30 and we have become familiar with those with whom we are in daily contact. Ejsing, I’m sure, has taken full measure of Shel and me. Most likely he has concluded we are young and naïve, crazy Americans over their heads, ill-prepared for what awaits them. For my part, I see Ejsing as a crusty, opinionated man, who sees himself as wise and tested. Above all Ejsing is cynical and bitter. During late evening conversations, he emphasizes ‘cold cash’ and the imperative for the strong to maintain confidence and not to yield.

The air is now cold and the ship sometimes rolls and pitches. As we approach the Cape Shel and I shove what we assume to be banned books into a canvas bag. Believing that if the books on black culture and revolution are discovered by customs we will not be allowed into South Africa, we hoist Trevor Huddleston’s Naught for Your Comfort, Lerone Bennett’s Before the Mayflower, copies of Ramparts magazine, and a dozen other titles up to the rail and into the sea. The deed is done as we stand at the stern as the ship steers close to Robben Island where Nelson Mandela is in the tenth year of a life sentence for treason.

After 19 days we have reached our destination. There is a final movie night and we gather to watch Cotton Comes to Harlem. Afterwards Ejsing, with whom I’ve become friendly, takes me aside urging me to remember the Danish maxim of not holding one’s candle beneath the table. The message is, he explains, be assertive not timid. We organize our luggage and watch the white uniformed pilot climb the rope ladder from his small craft onto our foredeck. He will guide the Diana Skou to its berth.

We are in parts unknown.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend