This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

17th January 1608 – Emperor Susenyos I of Ethiopia surprises an Oromo army at Ebenat; his army reportedly kills 12,000 Oromo at the cost of 400 of his men

Medieval map of Ethiopia, including the ancient lost city of Barara, which is located in modern-day Addis Ababa [Samuel C. Walker, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=109427725]

Ethiopia is a very long-lived state.

An Ethiopian state has existed since at least the 100s AD, when the Kingdom of Axum grew rich on the trade down the Red Sea between the Roman Empire and India.

However the Ethiopian Empire, the direct predecessor of modern Ethiopia, began around 1270, when it was founded by the Solomonic dynasty under Emperor Yekuno Amlak. Amlak claimed direct descent from the Axumite kings and also from the Biblical Solomon.

The Empire of Axum at its peak in the 6th century [Aldan-2, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=75096897]

The Ethiopian state dominated the Ethiopian highlands, and was an early convert to Christianity, which became closely tied to the state. While at first this was of great value to the Ethiopian state, as it helped facilitate trade and contact with the Mediterranean world, after the rise of Islam in the 600s and 700s, Ethiopia became more and more isolated and surrounded on all sides − by animist peoples to the south and west, and Muslims to the north and east.

Ethiopia came to view itself as the protector of the Coptic Christians, and in 1320, when the Mamaluks of Egypt began to persecute the Coptic Christians of Egypt, the Ethiopian emperor, Amda Seyon, threatened to divert the course of the Nile if the persecution of Christians did not end.

Mamelukes on horseback, etching by Daniel Hopfer (ca 1470-1536)

The 1300s was a good period for the Ethiopian emperors, who dominated most of the Muslim states in the Horn of Africa and extracted tribute from them, while managing to maintain their independence from the powerful Islamic Sultanates to the north.

Things were not to last; in 1415 a Muslim dynasty who were long time enemies of the Ethiopians established the Adal Sultanate to the east. This resulted in almost constant conflict between Ethiopia and Adal.

In the 1520s, Adal began to receive support from outside powers such as the Ottoman Empire, and built up a new advanced modern army, equipped with firearms. In 1529 they invaded Ethiopia and defeated the Ethiopians. In 1531 they invaded again, and began trying to wipe out the Christians for good.

It was during this period that the Portuguese made contact with the Ethiopians. Europe during the Medieval period long had a myth of a king called Prester John, who supposedly existed on the other side of the Muslim empires, and if contacted and coordinated with, could with his kingdom be the key to defeating the Islamic enemies of Christendom.

No such king existed. Originally he was thought to exist in India or central Asia. This is likely because of stories from Nestorian Christian monks and missionaries who had succeeded in converting some people in Central Asia, India and China during the Middle Ages, and exaggerated the scale of these conversions in their writings.

Nestorian priests in a procession on Palm Sunday, in a seventh- or eighth-century wall painting from a Nestorian church in Qocho, China

Over time, however, other suggestions were made as to the location of Prester John’s kingdom. Perhaps it wasnt in Asia, but rather in Africa?

So, when the Portuguese encountered the Ethiopians, battling their Ottoman enemies, they connected Ethiopia with Prester John. This helped facilitate an alliance between Portuguese and the Ethiopians against their shared enemies in the Adal Sultanate and Ottoman Empire.

After much conflict, the Ethiopians finally beat the Adal Sultans and sacked their capital. Both powers were however seriously damaged by the long conflict, and a new player had arrived on the scene.

In the far south of Ethiopian territory and beyond its southern borders, there lived a mostly pastoral people called the Oromo.

A contemporary photograph depicting dress and hairstyle varieties common to the Oromo culture [Mekonnen B.Gedefa, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=44498496]

The Oromo mostly herded cattle, and were animists, worshiping spirits and their ancestors. An Oromo legend tells of a great beast which began stalking the lands of the Oromo, eating its people one by one until they were forced to flee. The beast in this story is thought to embody hunger.

Likely due to lack of food, grazing for their animals or perhaps attacks by other peoples deeper into the interior of Africa, the Oromo in the 1500s began to migrate north into the heartlands of the Ethiopian empire.

Figures depicting three Oromo clans: the Barentu, the Borana, and the Lobo

What began with cattle raids, soon morphed into a large movement of people which now threatened both the mostly Amhara, Christian peoples of Ethiopia and the Somali Muslims of the Adal Sultanate. As the Oromo raided deeper into Ethiopia and Adal they slowly adopted innovations of the settled people such as horseback riding, which made them only more dangerous.

These invasions massively destabilised both powers and helped completely collapse the Adal Sultanate when, in a battle with the Oromo, their last Sultan was killed in 1583.

Anachronistic painting of the Sultan of Adal (right) and his troops battling Emperor Yagbe’u Seyon and his men

The Oromo had a unique structure to their society, called the Gadaa, with people divided into age regiments, with unique rights and responsibilities. Each age regiment would elect representatives to a council who would make decisions. People would move to the next age group after eight years and new elections would be held.

Children would become students of their elders around nine years old, then would begin military training around 17. They would assume a leadership role around 41, an advisory role around 49, become a judge in their 50s and 60s and a priest in their 70s.

This structure proved effective, and the Oromo not only conquered and raided but also absorbed conquered people into their society.

The conflict between the settled peoples began in the 1530s and slowly grew in intensity throughout the 1500s. Oromo raids and advances would be met with retaliation by the Ethiopians.

In the 1583, a young boy who was an Ethiopian noble called Susenyos was captured during an Oromo raid, and his father was killed. Susenyos went on to live for two years among the Oromo, learning their language and customs, until he was rescued by an Ethiopian military expedition. Susenyos was the nephew of the Ethiopian emperor and after his rescue resumed his place as a high-ranking noble.

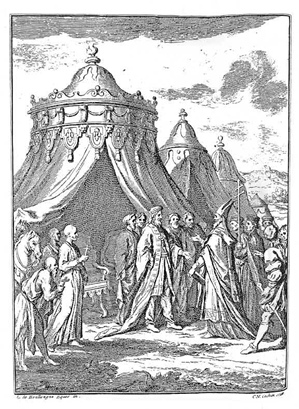

King Susenyos I receives the patriarch of the Latins

After his uncle’s death, the throne passed to Susenyos’ young cousin Yaqob. Susenyos attempted to seize the throne, but was forced to flee. He recruited many Oromo warriors to his banner and launched raids against the nobles who supported his cousin. Eventually In 1607 he defeated his cousin and became emperor.

A new civil war soon broke out as Yaqob’s body was never found, so an ambitious man claimed he was Yaqob and covered his face claiming he had been terribly wounded which was why he looked different.

At the same time, a new large Oromo army swept into Ethiopian territory. Susenyos led an army against them and won a decisive battle against the Oromo on 17 January 1608.

On an unstable throne, facing yet more Oromo invasions, and civil war, Susenyos hoped for Portuguese aid as his predecessors had once benefited from in defeating the Islamic invaders. Susenyos thought that by joining the Catholic church he would be able to bring foreign support.

Much to the outrage of the local Ethiopian church Susenyos converted to Catholicism in 1622, the only non-Coptic Christian ruler in the history of the Ethiopian Empire.

Late 17th century portrait of Giyorgis of Segla (c. 1365 –1425), an Ethiopian Oriental Orthodox monk, saint, and author of religious books.

Little help came from outside, save some Jesuit priests, and the change in religion brought on more rebellions.

After a brutal battle against Coptic rebels one of his sons said to him:

“These men, whom you see slaughtered on the ground, were neither Pagans nor Mahometans, at whose death we should rejoice—they were Christians, lately your subjects and your countrymen, some of them your relations. This is not victory, which is gained over ourselves. In killing these, you drive the sword into your own entrails. How many men have you slaughtered? How many more have you to kill? We have become a proverb, even among the Pagans and Moors, for carrying on this war, and apostasizing, as they say, from the faith of our ancestors”

In 1632, Susenyos had no choice but to convert back to Coptic Christianity.

The Oromo would slowly begin to settle and integrate into the Ethiopian political and religious systems, converting to Christianity or Islam. Many still maintained their Gadaa system however.

Today the modern Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia’s largest ethnic group is the Oromo, which makes up about 35% of the population. The Amhara are about 27%.

Oromo protests [https://www.flickr.com/photos/13803392@N07/1406935284/, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=95799771]

Despite having an ethnically defined region within Ethiopia, many Oromo today still believe the government remains dominated by the Amhara in Addis Abiba.

An Oromo Liberation Front rebel unit, regrouping in northern Kenya in 2006 [Photo by Jonathan Alpeyrie/Getty images, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4171558]

Oromo separatist groups have battled the central government in recent years, with the Oromo Liberation Army signing a peace agreement with the government in December of 2024.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend