This not a revisionist history, nor is it a work of scholarship; it is a brief polemic. It intends no exculpation for wrong-doing and it denies no-one’s suffering. This the second of a three-part series. The first was published on 19 January.

The British not a colonial power in Southern Africa? That seems an unlikely proposition, but if you insist on calling them colonialists you will surely have to concede that they were colonialists by accident.

They were invited by the Dutch to occupy the southern tip of Africa to protect the Cape sea route from control by the French, and they complied. It was the sea they were interested in, not the land. By no stretch of the imagination did they take the Cape by conquest, but rather by two mock battles that resembled scenes from a Gilbert and Sullivan comic opera.

Did they extract wealth from southern Africa? No. In spite of allegations in respect of diamonds and gold, they made a loss. Did they dominate their new territories with colonial jackboots? Hardly. Nor did they acquire possession of the Cape as a consequence of avarice, for there was precious little in the Cape to be avaricious about.

A distinguished contemporary South African historian refers to “… the British imperial conquest of Southern Africa.” This is a fiction. In fact, it was not the putative British imperialist thrust that damaged South Africa, it was, as I hope to show, the failure of that thrust at the conclusion of the Anglo-Boer War that led to the formation of Union and the apartheid state.

Some of the Cape Dutch quibbled about the British occupation, but it was far from being universally objectionable to the light-skinned inhabitants, and for the dark-skinned it was probably an irrelevance. Initially the British did little to interfere with established patterns of daily existence, and there were many developments under its occupation that materially improved life at the Cape, including the elimination of the VOC’s corrupt trading practices, the importation of agricultural implements, the establishment of an independent judiciary and a professional bureaucracy, and a lenient tax regime accompanied by much-needed capital inflows.

Cape agricultural producers discovered they now had access to the global markets of the British Empire and to European markets suffering from war economics. Tariffs on wine exports to Britain were temporarily lifted, and wheat along with wine became the mainspring of a new wave of prosperity. In the longer term a huge and hungry British market for Merino wool was created, a market which reached its apogee in the 20th Century, when Afrikaans wool farmers who nurtured a vested grudge against British colonialism in South Africa nevertheless took the devil’s shilling by selling their product at inflated prices to the British government during the two World Wars.

What is there not to like?

Roads, rail links and mountain passes were built, shipping increased, banks, insurance companies and newspapers free of censorship were established (including newspapers owned by the dark-skinned), postal and telegraph services were implemented and private business flourished. Freedom of conscience has of course been recognised throughout the period from 1652 to the present, even though religious persecution continued in Europe well into the 19th Century. If this is colonisation, what is there not to like about it?

What of the political consequences of British occupation? It took a little time, but the British put the Cape irrevocably on the road towards constitutional freedom – irrevocably, that is, until 1936 when it was revoked by Hertzog’s government. Sniffy liberal historians damn with faint praise the British 1853 colour-blind constitution on the grounds that it was qualified by a property-owning condition that had the effect of excluding the dark-skinned.

I have at least two objections to this quibble: in the first place, it was a franchise more progressive than existed (for instance) in Britain at the time. (By the conclusion of the first world war in Europe, 40% of the British soldiers fighting and dying for British “democracy” did not have the vote, nor did any of the British women keeping Britain’s industrial base going throughout the war years). The franchise was certainly an advance on many other national constitutions. In the second, the property qualification became less onerous over time, and the Cape constitution, albeit qualified, represented a non-racial platform which − had its life been extended − would inevitably have been subject to progressive revision.

Ordinance 50 of 1828 conferred full citizenship on all inhabitants of the Cape, on the grounds that they were all equally British subjects, and on at least two occasions an absolute commitment to colour-blind citizenship rights was endorsed by the Cape legislature. That this binding legal commitment to non-racialism has received such grudging recognition is all the more astonishing when it is realised that it took another 180 years – until 1994 − before a similar commitment to non-racialism was made.

I search in vain

As we all know, trading in slaves was made illegal in 1808, and slavery was abolished in 1834, at a time when the practice of slavery continued on its diabolical path in the rest of the world outside of the British Empire. In 1872, the colony attained responsible government under the leadership of its first Prime Minister, John Molteno, and acquired legislative independence from the British government. The commitment to treat the dark-skinned as being free of discrimination was explicitly reaffirmed by the new Cape government, which struck down opposition motions to restrict voting qualifications in 1874, and again in 1878. I search in vain for footprints made by the colonial jackboot.

Conflicts on the eastern frontier continued, again with setbacks, losses and casualties experienced by all the parties to the conflict. The British Colonial Office was far from unsympathetic to the interests of the dark-skinned participants in the struggle, but the might of the Xhosa military machine was finally broken not only by the agency of the light-skinned settlers, but by the tragic consequences of the influence wielded by Nonqawuse and the superstition she peddled, which resulted in death by starvation of 40 000 Xhosa people and the slaughter of 400 000 head of cattle.

None of this serves to overlook the retrogressive attempts by light-skinned leaders to curtail democratic freedoms. I am challenging the narrative of colonialism and racism in South Africa, not denying the universal human propensity for domination.

It is often held that the British 1820 settlers arrived in Africa with a built-in sense of national and cultural superiority. For all I know, this may be true. Some of those settlers were British Israelites, a scion of the British people who claimed to be God’s chosen people. Irritating as such an assumption may be to all others who haven’t been so chosen, the assumption of superiority recognises no mitigating or exacerbating factors like skin colour or nationality. We are all uniformly the subjects of its pity or its scorn. Be this as it may, those settlers were brave and dogged, and contributed immeasurably to the agricultural wealth of the nation that was to become South Africa.

Much is made of the British annexation of Griqualand West in 1871 following the discovery of diamonds in the Kimberley area, but is this a manifestation of colonial avarice? Since the mining was undertaken by private prospectors and speculators − mainly British, but far from being exclusively so − it was not the British Crown that benefited from the annexation.

Colonialist megalomania

It was an action that ensured a legal and administrative framework conducive to the pursuit of mining, and notwithstanding his colonialist megalomania, Rhodes cannot be blamed for coming first in that pursuit. On the subject of alleged British colonial cupidity, and getting ahead of myself in the chronology of this three-part argument, it is often held that the British were drawn into war with the Transvaal (the SAR) by the lure of gold, but it is a little-known fact that the Bank of England doubled its gold reserves in the 1890s − before the War − by purchases on the open market. It did not need to own the Transvaal, in other words, to benefit from its mining industry.

The British also annexed Natal. This led to the Zulu Wars, conducted at considerable cost to the British. In terms of the numbers killed and in respect of the widespread social disruption it caused, what the British jackboot did to the Zulus at Ulundi in 1879 cannot bear comparison with what the barefoot Zulus did to their fellow African tribespeople earlier in the century.

The Zulu warriors were merciless and savage, took no prisoners, and habitually slaughtered women and children. It is estimated that over a million dead were the consequence of Shaka’s wars, the repercussions of which extended beyond the Limpopo, and it is a matter of some wonder that, far from being held accountable for the psychological harm his reign of terror might have inflicted on the contemporary consciousness, Shaka has had an international airport named after him.

The Zulu might and mission did not die along with Shaka, and we may be sure of a resurgence of that mission under Dingaan and his successors had the British not annexed Natal. There were surely few if any tears shed by the other non-Zulu dark-skinned inhabitants of the southern African sub-continent following the British victory. (Co-incidentally, more extensive commentary on this subject was given in an open letter to the Minister of Education by Tiego Thotse, published by the Daily Friend on 14 December.)

What about the ‘imperialist” British relationship with the Boer republics? Without much trouble, both were granted their independence in the 1850s. The British also capitulated to the Boers after the battle of Majuba Hill with hardly a whimper. Imperialism should be made of sterner stuff.

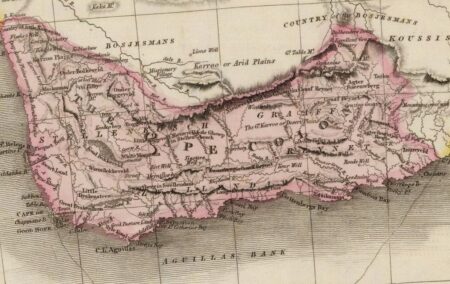

[Image: Map of the Cape Colony in 1809 − John Pinkerton, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6032234]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend