As a South African interested in military history, I am drawn to tales of South African heroism under fire. Over the past few years, however, I have come to realise that for every South African military triumph, there exists an equally monumental ‘cock-up’.

South African courage at El Alamein in Egypt in 1942 must be contextualised in the wake of the shameful surrender of the South African garrison at Tobruk in Libya months earlier. So too, the lionisation of the Springbok soldier at Delville Wood in France in July 1916 must be tempered by the folly displayed only months earlier by South African troops at the Battle of Salaita Hill on 12 February 1916, 109 years ago today.

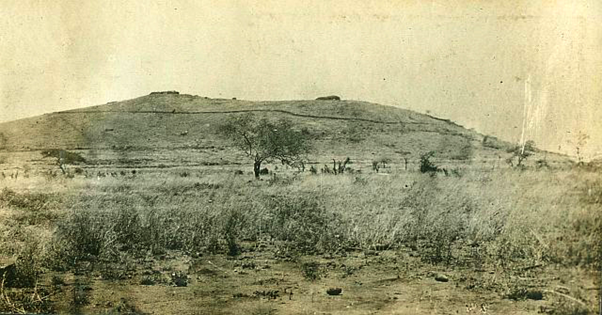

Salaita Hill, described by East Africa-based novelist Steve Braker as a ‘mound’, was strategically situated just inside the Anglo-German colonial border of British East Africa [Kenya].

In 1915 German troops under the wily Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck had occupied Salaita, and the Tsavo region in general, so they could observe British supplies transported along the Uganda-Kenya railway, raid British assets in the region and defend against any British attacks into German East Africa [GEA].

Salaita Hill sometime in late 1915 or early 1916. The dummy trenches near the top of the hill are visible but the occupied trenches at the base are not

In early 1916, British forces in East Africa had been reinforced with the arrival of South African, Rhodesian and Indian troops, and were poised to push German forces back across the border and neutralise German power on the continent.

The British commander in the region, Major-General. Wilfrid Malleson, was keenly aware of the threat the Germans on Salaita posed to the region and realised that they needed to be removed. Malleson’s decision was also motivated by his imminent replacement by the famous Boer statesman soldier, Jan Smuts, who had been appointed as Malleson’s successor on 6 February 1916. Five days later, Malleson, determined to go out with a victory to his name, drew up plans for an assault.

Malleson’s plan was based on the misguided notion that Salaita was manned by approximately 300 German officers and Askaris [Africans in the German colonial armed forces] without artillery.

Frontal attack

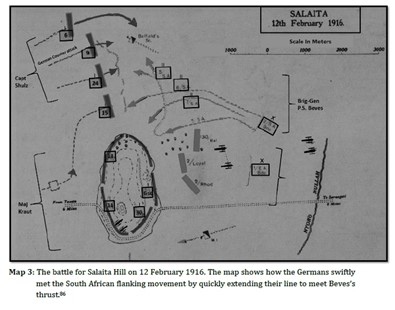

It proposed limited frontal attack from the west by the more experienced East African Brigade made up of the 2nd Rhodesia Regiment, 2nd Battalion Loyal North Lancashire Regiment and the 130th Baluchis Regiment, and a fully-fledged flanking attack by elements of the 2nd South African Infantry Brigade [SAIB] under Ladysmith veteran Brigadier-General P.S. Beves from the North West.

The Rhodesians, Lancs and Baluchis, recruited from modern-day South-East Pakistan, were supposed to pin down the defenders whilst the fresh South African troops flanked them, assaulting the northern tip of Salaita.

Battle Map [Katz, David Brock. (2017). A clash of military doctrine: Brig-Gen. Wilfrid Malleson and the South Africans at Salaita Hill, February 1916. Historia, 62(1), 19-47. https://doi.org/10.17159/2309-8392/2017/v62n1a2]

The South African troops were roused in the small hours of 12 February. By dawn they were 1000 metres from the base of the hill, and were ordered to begin the advance at 08.00. The Transvaal-recruited 7th South African Infantry regiment [7 SAI] would lead the attack with the 6th SAI [Natal and Orange Free State] on their right and the 5th SAI [Cape] on their left.

The morale of the Springboks was high. Sergeant Lane with the South African Medical Corps closed his diary entry for 11 February with, “I wonder what I shall write in these pages for tomorrow we fight!” 7 SAI machine-gunner ES Thompson records that his excitement nullified any thoughts of fear. Walter Stockdale, a rugged Maritzburg College old boy and Natal rugby forward in 6 SAI, wrote home that he was itching “to have a crack at the Hun”, and that his comrades were “wonderfully fit and happy.”

Act of incompetence

With the South Africans slowly advancing, Malleson ordered his artillery, two of the guns coming from the sunken cruiser HMS Pegasus, to open fire on German positions on the slopes of Salaita at 09.00. In yet another act of incompetence, Malleson’s targeting of German positions on the slopes was a direct contradiction of the reports given to him from South African aerial reconnaissance of the hill, which reported that the Germans were occupying trenches at the base of the hill and that the higher positions were decoys.

While many South African historians are quick to heap blame on Malleson and his outdated British Aldershot-style tactics, and insinuate that things would have been totally different had Jan Smuts been in command, it would be foolish to suggest that the South Africans were blameless.

600 metres into their advance, the South Africans came under intense fire from the approximately 1300 Germans occupying Salaita. In addition, the Germans, alerted by the approach of the Springboks and the artillery, ordered their 15th German Feldkompanie [FK] of approximately 200 Askaris and a few machine guns to counter the South African advance. This force, held in reserve behind the hill prior to the opening bombardment, added to the fire raining down on the South Africans.

As a result of this fire, German counter artillery, and thorn and barbed wire obstructions, progress toward the German positions slowed to a crawl.

Walter Stockdale recalled afterward that “hearing the bullets whistling by really made me feel like an awful coward” and that his comrades further in advance “were having a rotten time”. This stoic understatement belies the fact that casualties were starting to mount.

Unsure of how to proceed, many of the novice Springboks panicked, clinging to the earth or retreating to the nearby cover of bushes and anthills. 7 SAI machine-gunner ES Thompson recalls in his diary that his comrades “lay down for about half an hour with bullets zipping past all the time. My mule [carrying his machine gun and ammunition] bolted for the German lines, so I let him go, and… got behind an anthill.”

First-hand South African accounts of the battle and the shambolic retreat that followed are contradictory and highlight the manner in which the Springboks attempted to pin their shame on their comrades. Whilst it is generally agreed that the South African attack broke down around 10.30, accounts differ as to the nature of the subsequent retreat and the regiment responsible. In most accounts, 7 SAI is singled out as being the first to buckle.

The Natalians of 6 SAI on the right flank claim to have stormed and briefly occupied German trenches extending north of Salaita.

Old school mates

The history of Durban High School proudly states that one of their old boys, Captain Gordon Rennie of 6 SAI, had heroically captured two German trenches with his men but was forced to retreat and was mortally wounded doing so, the only consolation being that he was carried off the field by some of his old school mates.

Veterans of 7 SAI such as ES Thompson claim that the regiment’s D company [composed of Australian and New Zealanders employed in the Transvaal] had managed to infiltrate the first line of German trenches but could not build on their gains, as their compatriots in 5 SAI were reluctant to move forward in support. This is refuted by 5 SAI’s Regimental Sergeant-Major [RSM] Molloy. He claims, and this is corroborated by most of the maps produced to illustrate the battle, that 5 SAI was “ordered to move to the right flank of the 7th and fill the gap between them and the 6th.”

He goes further, claiming that the commanding officer of the regiment, Colonel Byron, disobeyed a subsequent order from General Beves to abandon 7 SAI, and retire some 180 metres to protect the artillery.

Molloy describes how Colonel Byron led two of his companies in a mission to cover the retreat of 7 SAI and, later, 6 SAI, firing into the German positions with his own rifle.

Officer Commanding 7 SAI, Col Freeth, inspects the regiment in full marching order. [Ditsong National Museum of Military History]

Scapegoating aside, the various sources on the battle make it clear that the South Africans were not physically or mentally prepared for battle. The 2nd SAIB had only been recruited four months earlier and, although most of the officers and NCOs had combat experience in the Boer War or the German South West African [GSWA] campaign of 1915, most of the troops were inexperienced.

General Berrangé, the officer in command of the 3rd SAIB [which was still in transit to East Africa at the time of Salaita] later reported that the South African troops destined for the East African front were woefully unprepared, with most troops only receiving their uniforms and weapons on the ships departing from Durban.

The result was humiliating for the novice Springboks, who had been brimming with confidence hours earlier. The British commander of a machine gun company attached to 5 SAI, Captain Frank James, criticised their reluctance to fire fearing that this would draw return fire. 6 SAI lost contact with a mounted force tasked with protecting their exposed right flank. So, when the two German counter-attacks were launched, the result was a chaotic withdrawal.

The 200 Askaris of the 15th FK commanded by Major Georg Kraut, having halted the South African advance, were ordered to fix bayonets and charge just after midday. About the same time the 6th, 9th and 24th FKs, under Captain Shulz, launched their own counter-attack which threatened to cut off and decimate 6 SAI.

Shell-shocked Springboks

With cries of “Piga! Piga!” [Shoot! Shoot!] the Askaris crashed into the shell-shocked Springboks.

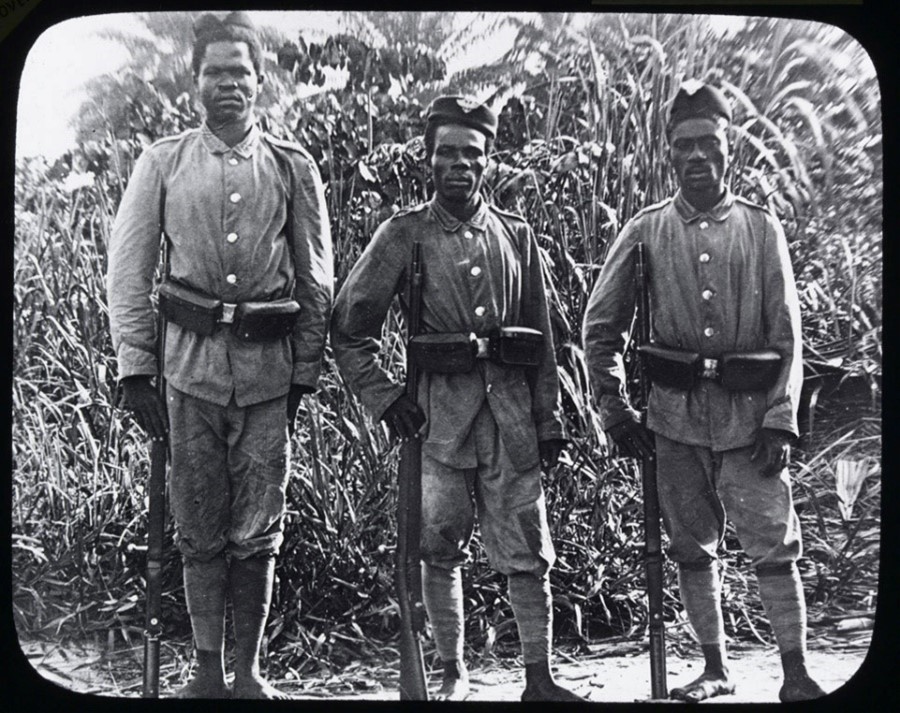

Mzee Ali, a Tanzanian Askari with the 15th FK, recalled gleefully many years later that, although the South Africans had an advantage in numbers, “during our bayonet charge they retreated − no, in fact they turned and ran. These white men, with their superior race, with their heavy artillery and overwhelming fire-power, turned and ran like rabbits.”

General Beves ordered the retreat at around 13.00. However, according to the sources, most of 7 SAI had already bolted before the bugle sounded.

The result of the battle was an overwhelming German victory. The South Africans lost 139 men killed, wounded or missing [nearly half the casualties they incurred during the entire GSWA campaign]. The German losses, on the other hand, were slight, with 10 killed and 33 wounded.

According to Maj-Gen. Malleson, the debacle was a result of South African inexperience and cowardice. Malleson reported that the South African commander, General Beves acknowledged this saying “My men have gone; it is impossible to rally them here. I am very sorry.” Additionally, Malleson claimed that other South African officers echoed Beves’ apology, one South African officer adding that his men were “kicking themselves with shame and disgust.”

Malleson, whose lack of strategic creativity and misguided use of artillery significantly contributed to the defeat, is only partially correct in his appraisal of the Springboks. This calamity was not a result of South African lack of experience, training or courage.

It was their hubris.

Mzee Ali’s description of the chaotic South African retreat belies the racist over-confidence with which South Africans have frequently approached battle.

According to historian Dr. Rodney Warwick, South African troops, despite cautions by the British officers in East Africa who had struggled against the Askaris for over a year, belittled their Askari opponents as “kaffirs”. The subsequent realisation that they had been bested by their so-called ‘racial inferiors’ is evident in the descriptions of the Askaris penned by South Africans in memoirs and after-action reports.

In these documents, the Askaris are differentiated from other East Africans as physically superior and descended from martial tribes. A letter written by 5 SAI’s RSM. Molloy highlights the initial contempt South African soldiers had for their African adversaries and the queer manner in which they came to reconcile their racist illusions with the reality that brutally confronted them at Salaita.

“Our black enemies”

“That we have a lot to learn in the way of bush fighting from our black enemies, and that in spite of all talk to the contrary… he is resourceful, brave and well trained for this kind of fighting. He is however a brute and does not hesitate to mutilate and kill all wounded or prisoners… the ‘Askari’ as he is called.”

Askaris in German service. [National Army Museum, United Kingdom]

This tale of incompetence and hubris has an ironic and fitting conclusion. The complete rout of the 2nd SAIB was only averted due to the intervention of Indian troops from the 130th Baluchis.

The Baluchis, held in reserve at the start of the attack, were ordered to support and cover the retreating South Africans. The Baluchis met the Askari bayonets head on and stabilised the line, allowing the Springboks to retreat without further molestation.

After the battle, the Baluchis returned one of the machine guns abandoned by the Springboks in their panic, with a note which read: “With the compliments of the 130th Baluchis. May we request that you no longer refer to our people as ‘coolies’.”

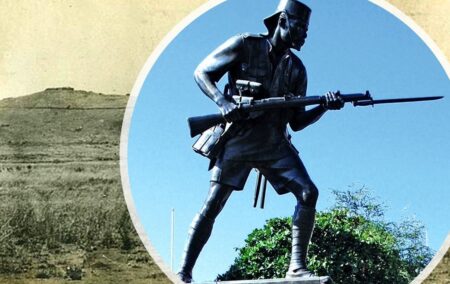

[Image: Askari Monument in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania dedicated to Askari who fought in the East African Campaign of World War I, superimposed on a photograph of Salaita Hill]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend