As US president Donald Trump continues to shoot the American economy in the foot, China will emerge as the global trade leader.

China has seen this movie before, and this time, it is ready. In 2018, during the first administration of President Trump, the US began to levy tariffs on Chinese imports into America.

Whereas US tariffs on Chinese products used to be in line with those on the rest of the world, at an average of 3%, they skyrocketed to nearly 20% by the end of Trump’s presidency, and remained there during the Biden administration. Whereas very few Chinese products attracted tariffs before 2018, two thirds of Chinese exports to the US were now affected.

This was a true trade war.

China responded in kind, of course, and its average import tariff on US goods rose from 8% to 21% over the same period. From very few US products being affected, China now taxes over 58% of imports from the US.

At the same time, China was subjected to technology import and export bans by the US, in the (likely vain) hope that it would curb Chinese spying via telecommunications products, and would retard China’s progress in high-tech fields such as artificial intelligence.

Wake-up call

Trump’s first term was a wake-up call for the Chinese government and Chinese companies, and they have spent the last six years preparing for the rematch. And while Trump might believe that America has a weight advantage over China, he has not accounted for the fact that China has options, and can outlast American trade aggression.

In fact, despite a renewed trade war hurting companies and consumers in both countries, China is likely to come out of such a war stronger.

China’s communist government and major companies have been working hard to diversify their businesses to become less reliant on the US, both as a source of imports and a market for exports. This has been described as the great reallocation.

Many companies have relocated, not to the US (which Trump seems to expect), but to third-party countries, in regions such as south-east Asia and Latin America.

In part, these moves are motivated by the search for lower-cost manufacturing locations, as prosperity, and consequently wages, rise in China and the country establishes increasingly onerous environmental regulations.

In part, however, Chinese companies are relocating their operations elsewhere to minimise the risk of tariffs directed at China, and to diversify their own exposure to world markets.

China has also been reducing its reliance on trade altogether. While trade accounted for 64% of China’s GDP in 2006, in 2023, it represented only 37% of GDP. As the Chinese people grew more prosperous, the country’s domestic economy became more important as a consumer market.

Chinese exports to the US account for only 15% of its overall exports. This is not an insubstantial number, but losing some share of that is hardly the sort of dent that will make Xi Jinping cry “uncle”.

And while the US economy is still some 50% larger than that of China, in nominal terms, China is the largest trade partner for 124 countries (including South Africa). The US is the largest trade partner for a mere 56 countries.

Belt and road

The Chinese government has spent the last two decades cultivating relationships with other countries, primarily in the developing world. Its New Silk Road (or Belt and Road) initiative, which began in 2013 and is supposed to run until 2049, lies at the heart of the Chinese Communist Party’s foreign policy.

Spanning over 140 countries, accounting for 75% of the world’s population and half its GDP, the initiative comprises targeted infrastructure investments to facilitate trade, reducing trade costs and shipping times, and lifting millions out of poverty.

While the US is a large market, it is also fairly saturated. Like other advanced economies, the US is expected to grow at about 2.2% in 2025 (and that was the estimate before Trump started annoying friend and foe alike with tariffs). The EU is expected to grow at 1.6%. (South Africa lags even that, with expected growth of 1.5%.)

By contrast, all of the 50 or so countries that are expected to grow faster than China’s 4.5% in 2025 are developing countries outside Europe and the US, and most of them are in Africa. Long-term, that’s where the growth is going to come from, and the US has just put everyone on notice that it is not their friend.

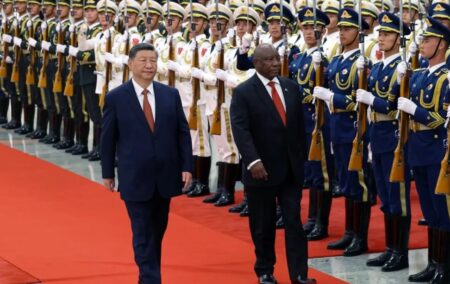

This is one reason why China has been fostering closer ties with African countries. The motive is not only economic, and it’s not only for short-term gain. China’s approach to Africa is a strategic move, that earns it soft power in a multipolar world.

In contrast to the aggressive trade war launched by Trump, China recently announced a zero-tariff deal aimed at making it the trade leader for the developing countries of the “Global South”.

Guess who developing countries will prefer to do business with? An aggressive, bullying, patronising America, or a welcoming, investing, zero-tariff China?

Trade warriors

Trump’s newfound mercantilist instincts might be extreme, but the US has long wielded its economic power aggressively to influence world affairs. The primary tool of its foreign policy has been sanctions.

Fully one third of the world’s countries are subject to American sanctions for one reason or another. Yet this tool is remarkably ineffective.

Cuba has been embargoed since 1958. If you were 20 when the US decided it couldn’t tolerate a communist outpost within paddling distance from Key West, you’d be 87 now. And yet, Cuba is still communist.

In 2017, Trump imposed sanctions on Venezuela, over illegal drugs, nationalisation of foreign-owned oil companies, and playing fast and loose with democracy and human rights. Yet Nicolás Maduro of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela remains firmly ensconced in power.

The US has maintained various forms of sanctions against Iran since the revolution in 1979 that turned it from a prosperous, progressive nation into a backward theocracy. Yet Iran has only become more dangerous in the intervening 46 years, aligning itself with Russia and China, funding international terrorism, and developing nuclear weapons.

Syria has also been on the US blacklist since 1979, but escalating sanctions haven’t exactly turned that benighted country into a liberal democratic paradise, either.

Russia was subjected to sanctions when it invaded Ukraine. That didn’t stop Vladimir Putin, but forced him to enter into closer alliances with other enemies of America, and right now, Trump is colluding with Putin on how best to carve up the victim in this fight.

The US has arms embargoes and economic sanctions on numerous countries that remain mired in war and despotism, including Myanmar, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Zimbabwe, and Libya. None of them are any closer to joining a peaceful, rules-based international order.

One might argue that sanctions worked against South Africa’s apartheid regime, but it was forced to the table as much by domestic opposition and its own poor economic policies as it was by international pressure.

Export controls

US export controls on high-end technology to prevent China from gaining a lead in fourth industrial revolution fields like artificial intelligence, are also not working so well. Despite not having access to the best American chips, China recently shocked the world by producing a generative AI model that rivals the best that America has been able to produce, at a far lower cost.

Besides, restricting technology exports to China will only motivate China to redouble its own research and development efforts. It already leads the world in many modern technologies, such as clean energy and electric vehicles. There’s no reason to suppose they cannot challenge the US in other fields, too.

Using sanctions (and their milder form, trade tariffs) as a weapon to bludgeon allies may be effective to extract minimal concessions, but it is hardly the most sophisticated or productive negotiating tactic.

Using them against enemies has historically been largely ineffective and often counter-productive.

Alienating allies

Even the European Union, which has operated in America’s shade for 80 years, is beginning to look elsewhere for friends.

Since the Covid-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Europe was in the process of “de-risking” its economy by moving some of its supply chains away from both of those countries.

In doing so, it was working very closely with the US. Then Trump promised that Europe was next on his list of trade war targets. That changes everything.

Last week, Ursula von der Leyen, the president of the EU Commission, said: “On China. We will keep de-risking our economies. But there is room to engage and find agreements that could even expand our trade and investment ties. It can lead us to a fairer and more balanced relationship with this giant. And that can make sense for Europe.”

“Just in the last two months,” reports the New York Times, “the European Union concluded three new trade deals.”

One of those deals is with Mexico, which is being blasted from close range by the Trump administration, which doesn’t seem to understand that brutalising Mexico’s economy is likely to increase, rather than decrease, migration pressure.

Anti-American alliance

The Financial Times reports that Trump is sowing the seeds of an anti-American alliance. That US import tariffs will cause domestic consumer price inflation and industrial disruption by taxing the raw materials and goods that American industry and consumers need is America’s problem.

However, the FT argues that Trump’s tariffs also threaten to destroy the unity of the Western alliance. This, it argues, would be a “dream come true” for Russia and China.

Quoting a senior European policymaker on whether the EU might now consider warming up to China once again, the FT reported: “Believe me, that conversation is already taking place.”

That Trump and his best buddy, Elon Musk, also openly support far-right populists in Europe will not endear the US to European politicians and businesses, either.

America’s allies will try to minimise the damage caused by Trump’s trade war, and will try to keep negotiation channels open. While they do that, however, they will also look elsewhere for new suppliers, and new markets. And once those new trade relationships have been established, the US is unlikely to win that trade back.

The damage that Trump will do to America’s economy, and America’s economic and diplomatic standing in the world, will take a long time to repair.

While America played the benevolent power that (for the most part) promoted free trade, human rights and democracy, leading the Western liberal democracies, anti-Western, anti-democratic, anti-capitalist alliances like BRICS+ always seemed to be naïvely over-ambitious.

The only thing Trump’s trade war will achieve is to make these anti-American alliances more relevant than ever. Talk about shooting oneself – and the free world – in the foot.

[Image: Xi Jinping, president of China, and Cyril Ramaphosa, president of South Africa, inspect troops in Beijing ahead of the ninth forum on China-Africa cooperation, held in September 2024. Photo: Free Malaysia Today/AP, used under a CC BY 4.0 licence.]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend