Cape Town is a remarkable city that bears a striking resemblance to San Francisco.

Here at the tip of Africa, Cape Town crouches beneath magnificent Table Mountain, a three-kilometre long slab of rock: an extraordinary natural phenomenon.

[Image: Barry D Wood]

We tarried a week in Cape Town before boarding the train for Johannesburg. It was a two-night, 36-hour journey through the desert like Karoo. In Joburg I began what became a deeply frustrating nine-week search for work. Most of our savings gone, we were down to R250, the equivalent of $300 (one rand = $1.25). We had a brief respite when an economics professor at the University of Witwatersrand had us grade several hundred essays, a weekend-long project that produced R160, enough for another month’s rent at the Quartz Hill Flats in Hillbrow.

I thought I had planned ahead. I had written to banks and mining companies and had several letters of introduction. Foolishly, I assumed I would be quickly hired.

Discouraged, I presented Shel with a fall-back plan. We could crew on a yacht, reach Mombasa, Kenya and get a ship for Bombay. We would return home having at least traveled around the world. Shel said no way. She had come this far but would go no further.

Life-changing break

Then came a life-changing break. We met Graham Hatton, the deputy editor of the Financial Mail − founded by the Financial Times and The Economist − a respected weekly with impeccable anti-apartheid credentials. Hatton escorted me into editor George Palmer’s corner office in the Carlton Centre and departed. I stated my case, but Palmer said it wouldn’t work and I was done. Crushed, I slunk back to Hatton’s office. To my astonishment Hatton said, “Don’t take that. Go back and tell him he’s made a mistake.”

With nothing to lose, I marched back to the editor’s office and said firmly, “Mr. Palmer, you’re making a mistake. I can produce good copy for you.” He listened and after a pause slapped the desk and said, ”All right, I’ll give you a two-month trial at R600 per month.” I was ecstatic. That night Shel and I celebrated with champagne and a fine meal at a Portuguese restaurant.

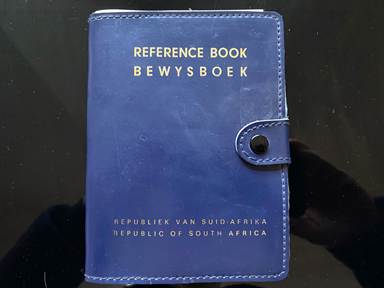

In apartheid South Africa, everything was about race and white domination. We recoiled from Africans calling us “baas,” “master,” and “madam.” We were shocked that on narrow sidewalks Africans invariably stepped into the street so we the privileged could walk unimpeded. Africans, but not whites, had to carry a passbook specifying tribal ethnicity and the locality where they were allowed to live. Public facilities were segregated. Africans had to be back in the townships − locations − by nightfall.

[Image: Barry D Wood]

As evil as apartheid was, it was a surprise to find that the news media was relatively free. There were daily news accounts of the humiliations and contradictions of South Africa’s race laws. In Pretoria, a shopping center under construction would not have toilet facilities for Africans because whites complained that restrooms for blacks would promote crowding, boost crime and drive down property values. An excavating company was fined for not having colour-coded earmuffs that would ensure that white workers did not use earmuffs previously worn by blacks. A construction firm was taken to court because it had allowed black painters to do work specifically reserved for whites.

We escaped the oppressive grip of apartheid whenever we could. We hitch-hiked the 320km to Swaziland, savouring the freedom in its relaxed social environment. We went to Lesotho, the landlocked, independent enclave surrounded by South Africa. And most of all we traveled twice to exotic, completely different Mozambique that was headed for independence.

Our longest adventure was traveling by air, rail and thumb through Botswana, Zambia and Malawi. We took the overnight train to Gaborone and made the long trek by rail up to Francistown near the Zambian and Rhodesian borders. Then we flew to Livingstone on the Zambian side of Victoria Falls. From the Falls we hitch hiked the 500km to Lusaka.

Irish couple

We were picked up by a young Irish couple who invited us to stay in their faculty apartment at the University of Zambia on the outskirts of Lusaka. Derek, a biologist, was optimistic about Zambia’s future. He argued that the completion of the Chinese-built Tazara Railway from the Tanzanian port of Dar es Salaam to Kapiri Mposhi in Zambia’s copper belt would spur development, raising living standards of Africans living along the route.

The next morning, we hauled our backpacks past tall cactus to the university gate on the Great Eastern Road and stuck out our thumbs hoping to reach Malawi by nightfall. Shel’s attractive presence was no doubt helpful in enticing drivers to stop. Our longest, most memorable ride was with a municipal dog catcher who was going past Chipata all the way to Lake Malawi. We huddled in the back of his van, in space usually occupied by stray dogs.

At the Malawi border Shel had to change into a long skirt, a fashion requirement for women decreed by President Hastings Banda. It was dark when we arrived at the Fish Eagle Inn, a charming resort run by an expatriate couple, consisting of several rondavel apartments and a dining area. It was culture shock to observe activity halted when from the dining room radio came the chimes of Big Ben and the 7pm start of the BBC’s “Focus on Africa.”

Shortly after dawn the next morning we watched six fishermen in a dug-out canoe silently paddling by, headed north. We swam in the warm, inviting water of Lake Malawi but were shocked when upon our return to Joburg we read that a hippo had the day before killed a swimmer at the Fish Eagle Inn.

We found Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) to be agreeable. Prices were low, the currency stable. Clean and tidy, my first impression of Salisbury (later Harare) was of Disneyland. Everything seemed to be in miniature. The military presence was pervasive but not overwhelming. Economic sanctions meant the cars were older and some consumer goods unavailable. As with Mozambique, race relations were relaxed compared to South Africa.

Fascinating

Mozambique was fascinating. The Mediterranean language, culture and cuisine were so different. Here was our first African revolution − peaceful and promising.

I enrolled in a Portuguese language course. But the shortcomings of Portuguese rule were obvious. Cab drivers in the capital were almost exclusively white. The fetid slums between the airport and city made Soweto look almost prosperous. In 300 years why had the Portuguese failed to build a highway between the capital and Beira, the second city 1,200 km north?

These were parts unknown, and after a rough start, things were coming right. Shel was returning to Ann Arbor to work on a master’s degree. NBC in London asked if I could report on Mozambique’s independence, June 25, 1975.

At last, I had made the transition from academia to journalism.

* The first part of this memoir, Parts Unknown, was published on 12 January.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend