Roger Crawford, who has died after a short illness, is remembered as a committed and influential liberal who straddled modern South Africa’s historic watershed, engaging the mounting challenges of the late-apartheid years and the no less testing environment of the post-1994 recovery with the same vigour, insight and humanity.

Largely behind the scenes, his role at the confluence of business, politics and international relations through the 1980s was a decisive contribution to determining South Africa’s transition to a post-apartheid future, with its economic institutions and potential intact.

His liberal convictions and the generosity that nourished them directed his probably underestimated efforts in the fraught political and economic turmoil of the 1980s and his role in influencing business relations between South Africa and the United States, no less than in his long and greatly valued association with the Institute of Race Relations (IRR), his charitable work, his keen involvement with his beloved St Andrew’s in Bloemfontein – where he and his brother, Michael, completed their schooling, and where his science teacher mother, Barbara, is fondly remembered – and in the sum of unadvertised gestures, memorable to friends and colleagues as the heartfelt expression of a good man who truly cared.

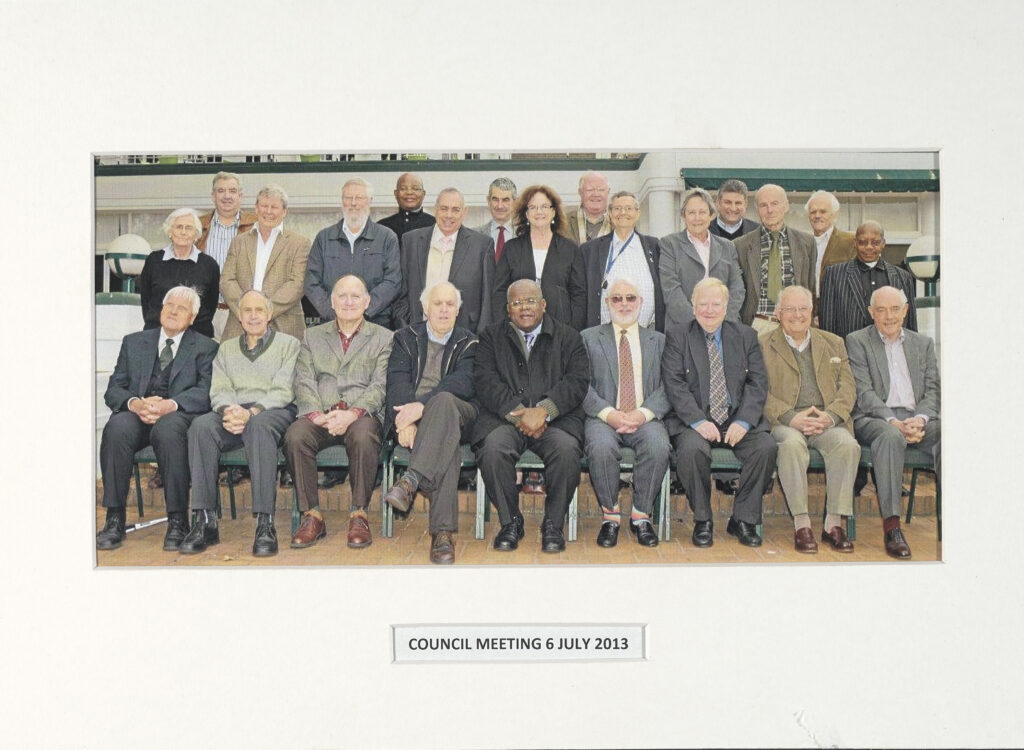

Crawford’s long association with the IRR began when he became a member in 1984. From the beginning of the 1990s he became increasingly active as a Council and later a Board member.

IRR Council meeting, 2013. Crawford is third from the left in the front row

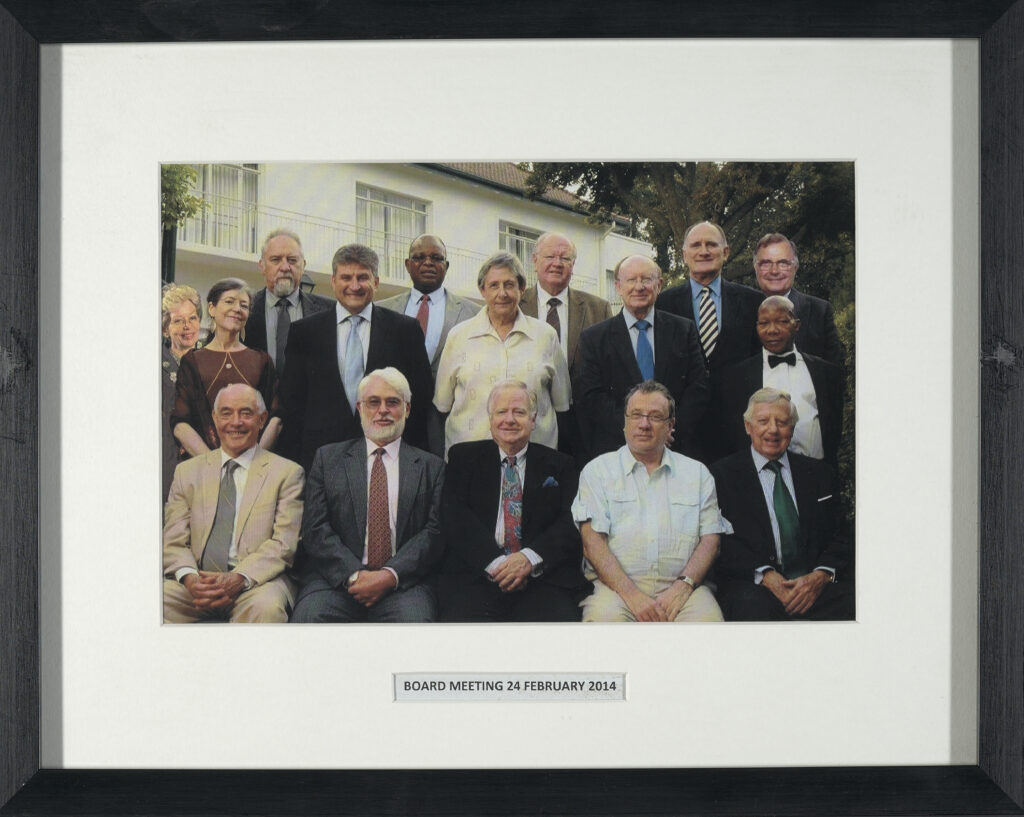

He was intimately involved in advising on financial aspects of the organisation, serving on and later chairing the Remuneration Committee. He was elected Vice President of the Council in 2016, and Chairman of the Board – for five years – in 2019.

IRR Board meeting, 2014. Crawford is second from the right in the back row

In a tribute yesterday, IRR CEO Dr John Endres said the IRR community “is deeply saddened by Roger Crawford’s death”.

“A member of the IRR for over 40 years, he played a critical role in guiding and building the organisation through his work as board chairman from 2019 to 2024 as well as his role on numerous board subcommittees and the IRR Council.

“As CEO, I came to appreciate his skilful chairing of board meetings and how he handled the occasional conflict with consummate skill, a wry smile and a deft touch. He provided rock-solid support to the Institute’s leadership in moments of pressure and was a great mentor to me and my predecessor, Frans Cronje.

“But above all I appreciated Roger as a person. He was kind and thoughtful, and spending time in his company was always stimulating and rewarding. He embodied the finest quality of the liberal ethos.

“As Alan Paton put it in his 1979 Hoernlé Lecture: ‘By liberalism I do not mean the creed of any party or of any country. I mean a generosity of spirit, a tolerance of others, an attempt to comprehend otherness, a love of liberty and therefore a commitment to the Rule of Law, a repugnance for authoritarianism, and a high ideal of the worth and dignity of man.’

“Roger conducted his life in accordance with those high values and set an example to the rest of us. We will miss him.”

IRR director of finance Rhona le Roux said of Crawford: “What a wonderful, clever, kind and inspirational person he was. May his memory be honoured for ever.”

Reflecting on Crawford’s pre-democracy role in the context of the US strategy of “constructive engagement”, the mounting resistance to apartheid, and the importance of US business in South Africa, former IRR CEO Dr Frans Cronje said: “Roger was important because he sat at the nexus between business – given his role in Johnson & Johnson – and the United States during the time of then US Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Chester Crocker and President Ronald Reagan, and the IRR, given its influence on events here in South Africa. That’s a story that has never really been written. And it was an important nexus, as it shaped a lot of how apartheid ended.

“The IRR realised that apartheid had already been defeated and that punitive measures (further sanctions) would have been counterproductive to facilitating a peaceful transition. That met a lot of resistance in many quarters, and all the people involved in advancing that argument did an important thing.”

Cronje added: “Sometimes the people who change countries or societies or relationships between them are not those who sit in official positions, but − almost as important, perhaps even more so sometimes − are back-channel diplomats who create circumstances where people in official positions can be successful.”

On a personal level, Cronje said, Crawford was “liked a great deal, which was not always easy in the world of policy and politics, the world I knew him in, and that stood out. He was probably the single most-liked person in the community that I ever encountered.”

Roger David Crawford was born in the final months of the Second World War.

He completed his schooling at St Andrew’s, matriculating in 1963, and spent the next decade and a half broadening his academic interests, and notching up qualifications. After a BA from the University of Natal, Pietermaritzburg in Economics, History, Politics, Philosophy, and English in 1968, he returned to Bloemfontein to complete a BA Hons at the University of the Free State in Modern African History & WW I Studies in 1972. Having been awarded the Abe Bailey Travel Scholarship and an Anglo American Scholarship, he gained a post-graduate certificate from the University of London in Theory and Practice of Education specialising in History and English literature in 1974. Finally, he was an awarded a Master’s, cum laude, from the University of the Free State for his thesis on Banda, Malawi and South Africa : A Contemporary Study, in 1978.

In biographical terms, the slightly more than 33-year outline of the next phase of his life is deceivingly summed up in the bald facts of his joining the American pharmaceutical, biotechnology, and medical technologies multinational Johnson & Johnson in November 1980, and remaining with the corporation until November 2013, having risen to the position of Executive Director for Government Affairs and Policy Implementation.

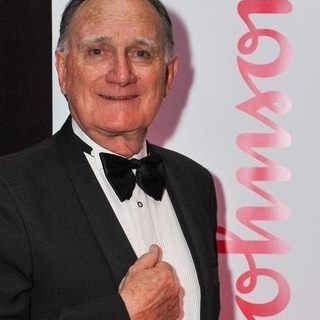

On the strength of his Johnson & Johnson career, Crawford was twice president of the American Chamber of Commerce (AmCham) in South Africa – in 1993-1994 and again in 2006-2008 – and earned the distinction of being made an honorary life member.

At the American Chamber of Commerce in South Africa Thanksgiving dinner, 2017

His intimate involvement with the establishment of the Johnson & Johnson Burn Treatment Centre at the Baragwanath Hospital in Soweto in 1991 earned him a Lifetime Achievement Award from the South African Burn Society, in recognition of his more than two-decade engagement with surgeons, nurses, allied health professionals and administrators in managing and developing the facility.

Crawford, with Victoria Makalima, assistant director for the Johnson & Johnson Burn Treatment Centre (left) clinical officer William Kalua and nurse Ester Manson from Kamuzu Central Hospital in Lilongwe, Malawi at the Burn Treatment Centre at Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital

What linked the high regard in which Crawford was held in AmCham and his Lifetime Achievement Award from the SA Burn Society was the responsibility he shouldered from the early 1980s as the inaugural full-time national coordinator of what, at the time, was commonly referred to simply as the Sullivan principles.

Named after American Baptist minister and Civil Rights leader Revd Dr Leon Sullivan, the Sullivan principles were a handful of key targets aimed at getting American firms operating in South Africa to voluntarily improve the working and living conditions of their black employees.

Sullivan had launched the initiative in the late 1970s as a response to apartheid, and to the growing calls for disinvestment. In essence the Sullivan principles called for non-segregation in the workplace, equal pay and employment practices, training and advancement of black employees, and efforts to improve employees’ living conditions beyond the workplace.

In 1980, at the IRR’s invitation, Dr Sullivan delivered the 32nd Hoernlé Memorial Lecture at Wits University in which he spoke of the “need to find a way to build a bridge between your white and your non-white population before havoc overtakes you all. It is to help build that bridge, if possible, by peaceful means, that the ‘Statement of Principles’ were conceived and initiated.”

It fell to Crawford to coordinate what Sullivan saw as “a humanitarian and economic effort, using companies of America combined with companies of the world, to help build that bridge and to help right the wrongs and injustices against blacks and other non-white people in South Africa before it is too late”.

It was no doubt true that, as Sullivan put it in 1980, “(whatever) other measures are attempted to assist with your racial conditions, such as ‘The Principles’, these efforts can and will only go so far, until nationally and constitutionally, and in practice, your racial segregation ends and individual freedom for all your people becomes a reality”.

In a 1983 interview with The Christian Science Monitor, it was clear Crawford had no illusions about the scale of effort required. While accepting that the 146 US companies that had become signatories to the principles by then “cannot have much impact on the South African social structure”, Crawford was undaunted. At the very least, the initiative gave important economic players the opportunity to “provide a leadership role”.

In having played a central role in helping to sustain South Africa’s economic engagement with the world at a time when the argument for disengagement was increasingly popular, he was, as Cronje puts it, a key contributor to “(creating) circumstances where people in official positions can be successful.”

Many years later, Crawford urged young South Africans in an interview with the UKZN Alumni magazine, In Touch, to “live your vision and never give up. It is better to try and fail than fail to try.”

Those who knew him know this was a credo he took to heart.

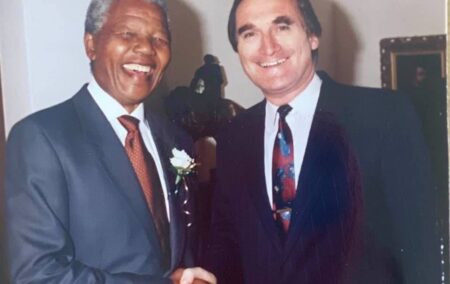

Alongside the main photograph accompanying this piece, Crawford wrote in a Facebook post of 18 July 2021:

“Today in South Africa is Mandela Day which marks the extraordinary life of Nelson Mandela. A few months before he became president I met him where we spoke about attracting investment and policies to grow the economy to eliminate poverty, inequality and to create jobs. He was amiable, charming and gracious. I expressed my surprise at his equanimity. He looked puzzled and, in that characteristic and deliberate speech pattern said: ‘I am at peace with myself, therefore I’m at peace with you.’”

He would have been touched by a friend’s observation: “Two outstanding leaders. Both humble and incredibly impactful.” And he would surely have smiled at the thought when another commented with likeable cheek, “Great picture Rog…did he ask for your autograph?”

In his last hours, wholly true to his character, Crawford himself expressed a brave and essentially selfless sense of what he felt gave his life meaning.

In a note to family and close friends, Cronje reveals, Crawford “said he was at peace because he had lived a life of purpose”.

“And for all the reasons I have given,” Cronje adds, “the era he lived through, the nexus of circumstances he confronted and how he confronted them, that idea of a life lived with purpose was very true of Roger Crawford.”

Crawford is survived by his wife Gill, their children Bronwen and Andrew, and five grandchildren.

The IRR extends its condolences to the Crawford family.