South Africans are, on average, poorer than they were a decade ago. Since 2013, the average wealth of South Africans has gone down in real (US$) terms 7.4%. Yet the world is, viewed as a whole, a much richer place, with average wealth per person increasing from $9,767 to $11,578 during the last decade, or 18.6%. Wealth across Asia went up by 42%, in the United States by 20%, across the European Union by 16.7%, in the Middle East and North Africa by 6%, and in Latin America by a comparatively miserly 3.4%. Only across sub-Saharan Africa was real GDP growth negative, at just under -1%, where economic expansion has not kept pace with demographic change.

Not only have people in South Africa been getting poorer, but much faster if matched against improvements in global wealth. Whereas their share of global per capita income was 60% in 2008, today its 50%.

This record places South Africa in the same growth ballpark as Argentina, which averaged -7.3% in the 15 years since 2008. The problem in Argentina was, according to the electorate, largely political; their response was to elect a radical reformist Javier Milei as president in 2023.

Does Milei’s example offer options to others facing similar challenges elsewhere?

This is the first of a two-part account, the second of which will be published tomorrow.

In 1995, Robert Timberg captured the intersecting lives of John McCain, James Webb, Oliver North, Robert McFarlane, and John Poindexter in The Nightingale’s Song.

This story covered the experiences of these five men, all graduates of the US Naval Academy at Annapolis, in Vietnam, and how that sorry foreign affair continued to shape their lives and haunt America and its various entanglements, including the Iran-Contra scandal, in the decades following.

The book’s title was explained this way: “Did you know that a nightingale will never sing its song if it doesn’t hear it first? If it hears robins or wrens … it will never croak a note. But the moment it hears any part of a nightingale song, it bursts into this extraordinary music, sophisticated, elaborate music, as though it had known it all along ….”

Ronald Reagan was the nightingale whose tune of patriotism made these men come alive in various positions in and around the White House and with varying stories of success and failure.

Webb became the Secretary of the Navy in between a distinguished writing career, his book Fields of Fire is considered a classic of Vietnam war literature, McFarlane, a US national security advisor, Admiral Poindexter, a succeeding national security advisor, Ollie North, an aide to the national security team, one of those at the centre of the Iran-Contra mess, and John McCain, who survived a Hanoi prison cell, a Senator and the 2008 Republican nominee for the US presidency.

Argentina has endured one nightingale in Juan Perón, whose political message of assertive nationalism became the political pride before the country’s economic fall. Eighty years since Peron’s rise, Javier Milei, the surprising winner of the 2023 election, promises to be another. His level of public support especially among younger Argentines has shocked the political establishment, whom he has denigrated as a “caste”.

But Milei’s success will depend not only on the tune but, as Reagan and Peron remind, its substance.

Legendary Success, Ignoble Failure

“You must always try to be the best, but never believe you are,” said Juan Manuel Fangio of his lesson about life. Argentina has its fair helping of legends, in politics as in sport, especially football, from Alfredo Di Stefano to Maradona and, more recently, Lionel Messi. One of its national heroes is Fangio, who won five World Championship Formula One titles in the 1950s, even though he entered the top echelon of what was probably the most dangerous era of the sport only in his late 30s. Unusually for motorsport, very few competitors would have publicly doubted his primacy in his era, probably the ultimate definition of success as a driver, an accolade perhaps only since shared with the Scotsman Jimmy Clark in the decade following.

Yet Fangio’s career path was, even for the 1950s, an unusual route to the top, one hardly blessed with a silver spoon, his origins a long way metaphorically and literally from the famous tracks of Europe where his global fame and fortune were eventually made.

Born into modest circumstances to immigrant parents in the town of Balcarce, today a five-hour drive to the south of Buenos Aires, Fangio dropped out of school at the age of 13 to work in a local garage, hopeful initially of a career as a footballer, his schoolboy nickname El Chueco, the bandy-legged one, referring to his skill in bending shots on goal.

After finishing his compulsory military service where his driving prowess was recognised by his appointment as the personal chauffeur of his commanding officer at VI Cavalry Regiment of Campo de Mayo, Fangio opened his garage in provincial Balcarce and started in motorsport, making his name in epically tough long-distance road-races in the 1930s driving modified American saloons. These were rough if garishly painted machines, two seats in a stripped-down saloon, the fuel tank lodged where a back seat would have been, cut-back mudguards, a basic three-speed gearbox transmitting power from a heavy, asthmatic six-cylinder engine, extra-lighting crudely rigged through the front quarter-windows, rudimentary suspension, and no safety equipment at all. It took real skill to coax speed from these racers, and extraordinary resilience and stamina to keep it together and on the road for up to three weeks with no support save from the co-driver, and dollops of resourcefulness.

Government helped, giving Fangio a step up the motorsport ladder. Having recovered from a near-fatal accident on the 1948 South American Grand Prix, which cost the life of his co-driver, a 20-day event spanning a distance of 9,580km from Buenos Aires to Caracas through Argentina, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia and finally Venezuela, Fangio got his big break in Europe with the intervention of President Juan Perón himself, turning heads in a Ferrari purchased with the support of the Argentine government.

Repainted in the national racing colours of blue with a yellow engine cover (the same as the famous Boca Juniors football team), the car was unusual for that era in being emblazoned with decals of YPF, the national oil company.

Today Fangio, known as El Maestro (“the master”) and El Caballero del Camino (“Knight of the Road”), is revered as a national hero, and was accorded a state funeral on his passing in 1995.

[Image: Greg Mills]

A race track and world-class museum were created in his name in Balcarce, still a sleepy provincial farming town famed for its potato production and Alfajor confectionaries, with a population of just 45,000.

In the 1930s, when Fangio was growing up, Argentina was ranked the sixth-largest economy worldwide, much of this based on a combination of natural resources and rapid immigration from Europe. Technology helped – particularly the advent of refrigerated shipping – to fuel the 50-year Argentine “Golden Age” from 1880, making possible frozen beef exports. By 1914, 80% of Argentina’s exports were agriculture products, 85% of which were shipped to Europe, and not all of it meat. Grain and oilseed exports increased exponentially, from a total of some 17,000 tons in 1880 to over one million tons a decade later; by 1910 Argentina was second only to America in wheat exports.

The so-called “Revolution of ‘43”, signalled a change that has since shaped Argentine politics and economics whatever the regime type, civilian or military, left and right coalescing around a brand of Argentine populism in Perónism, essentially a political addiction to overpromising and overspending. This has led to frequent crises and deep-seated economic problems including high inflation and indebtedness.

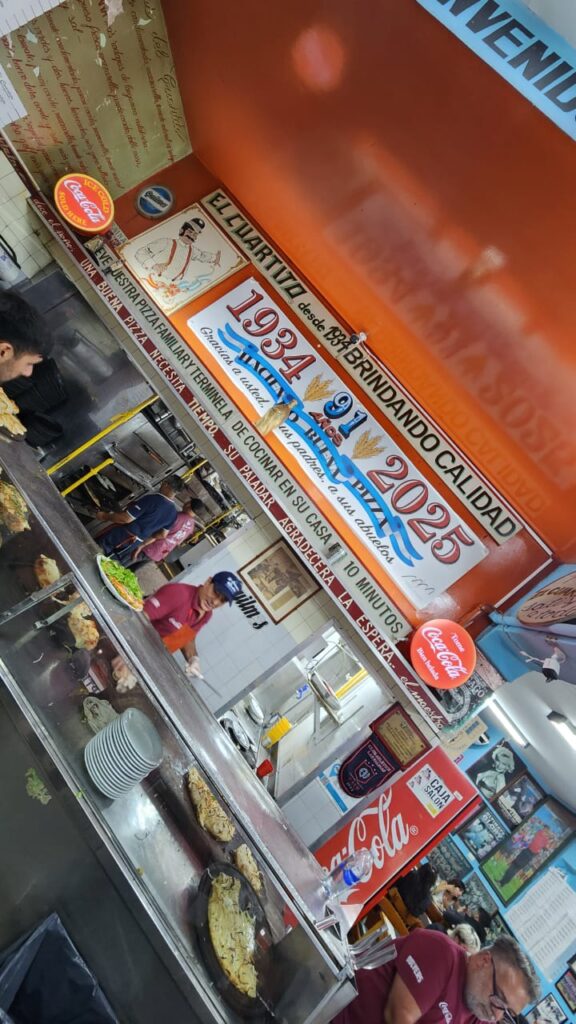

One of the most expensive places in the world. [Image: Greg Mills]

The coup of 1943 created a government modelled after Benito Mussolini’s fascist regime. Among the military leaders was Colonel Perón. Jailed briefly, he took power in democratic elections in February 1946, continuing where the junta had left off with a “corporatist” strategy, focused on drawing the political and working classes closer together through mobilisation of the unions, and adopting a radical import substitution industrialisation and economically redistributive policy to create social peace and a firm political constituency among the poor to whom goods flowed and the elites who profited from his patronage and preferences.

Please Pay for Me, Argentina

Aided by his wife, the charismatic Evita, Perón’s regime delivered improvements through redistribution, nationalising the central bank, electricity and gas, urban transport, railroads, and the telephone. This economic philosophy has been perpetuated in Argentine politics, fuelling impossible expectations, a perennial habit of overpromising and overspending. High inflation and indebtedness have inevitably followed, as has political turbulence.

Casa Rosada and “Evita’s” balcony [Image: Greg Mills]

Perón was ousted in 1955 by another coup. Further putsches followed in 1955, 1962, and 1966, interspersed with periods of military government. Perón regained power in 1973, but died a year later, passing control temporarily to his third wife, Isabel, toppled by yet another military coup two years later. The populism of Perón perpetuated through all these regimes, a tendency of weak institutions and strong personalities, where power supplanted ideology as the guiding principle.

Between 1946 and 2023 Perónist candidates won ten of the 14 presidential elections in which they were allowed to participate, encompassing the periods of Juan and Isabelita Perón (1946-55 and 1974-76) and, more recently the husband-and-wife presidencies of Nestor Kirchner and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner (2003-07 and 2007-15 respectively). Additionally, presidents Hector Campora (1973), Carlos Menem (1989-99) and Eduardo Duhalde (2002-03) are all considered Perónists, despite their varying ideological tendencies. After a short interregnum of the Cambiemos (“Let’s Change”) government of Mauricio Macri, the former Mayor of Buenos Aires, between 2015 and 2019, the Perónists came back with Alberto Fernández, and his deputy, the seemingly politically immortal Cristina Kirchner.

Then followed the break signalled by Milei’s election victory in November 2023.

Encompassing fascist, liberal and left-wing regimes, Perónism represents less of an ideology than a political platform. It is akin to a “restaurant chain where each venue has a different theme”, says the strategist Franco Moccia. In the words of law professor Emilio Cardenas who served as Menem’s Ambassador to the United Nations, Perónism is an “empty capsule”, which can “be filled with virtually any ideology that you want, especially if you disguise yourself as a Christian. You can be Perónist and Marxist, or a military government and Perónist. It tempts politicians continuously.”

And while Perónism, which mixes elements of nationalism, statism, and labourism with populism, has proven robust as a political formula to gain power in Argentina, it has proven less so as an effective political and governance means to run the economy. The International Monetary Fund has, as one measure of this economic train-smash, overseen 21 bailouts to Argentina, including its largest-ever programme in 2017, and one that ended the 2002 default. Like the barman to the alcoholic, the Fund is warming up for a last bailout in 2025.

Yet this external tool of discipline has so far enjoyed scant long-term positive impact. Argentina has maintained a boom-and-bust logic of overspending, fuelling a reckless printing of money, rampant inflation, and forex crises despite a surfeit of natural and human resources.

Ironically, in the 21st century, Perónism was partly saved by the success of the private sector. Farming in Argentina had boomed, bringing prosperity to places like Fangio’s Balcarce, driven by a rise particularly in the price of soya and by higher outputs and efficiencies from investments made by the private sector in agriculture methods and seed and planting technology. The agriculture sector brought in over $50 billion a year in exports by 2023, a windfall which helped to mask the serial failings of various Peronist governments, but regardless, a source of income on which they quickly moved to slap additional export taxes.

Such flaws included the handling of the oil and gas giant YPF, Fangio’s erstwhile sponsor, a company which has remained a target of Argentine nationalism and populism. In 2012 in response to her failed fiscal austerity programme, President Cristina Kirchner proposed the renationalisation of YPF, blaming the Spanish company Repsol, the majority shareholder, for the energy trade deficit. The bill was passed in Congress, consolidating the earlier enforced sale of YPF shares by Repsol to a Kirchner loyalist. The stink of corruption wafted steadily through the corridors of power.

[Image: Lyal White]

Yet, with few notable exceptions, the private sector, for all its complaints about the costs of hyper-inflation and instability brought on by overspending, has been largely complicit or at least largely passive in its relationship with the Perónists, with many businesses making their money through protectionist and preferential practices.

In this respect, Perónism has proven more than simply a path to power. Instead, it has represented a system of government in which there are a multitude of beneficiaries, not least the business sector, making money in an environment of “assisted capitalism” – protected by laws and procedures, critical of the administration in one breath while moving their money offshore across the River Plate to Uruguay to avoid taxes in another.

For this and other reasons, undoing statism is never easy. These policies ensured the political support of the masses through subsidies and preferences. For example, to ensure his 1946 election victory, Perón persuaded the president to nationalise the Central Bank and extend Christmas bonuses. Such spendthrift redistribution, while politically expedient, has served repeatedly to destroy capital accumulation, while attempting to baulk the inevitable reality of internal budget constraints and the underpinnings of global competitiveness.

In the process, Argentina has proven that you can do very badly despite a huge natural resource advantage in agriculture, oil and mining. It is a vast but empty land, the world’s eighth largest with a population of just 46 million. India, the world’s seventh-largest, has a population 28 times greater.

Living beyond Argentina’s means has led inevitably to a rapid accumulation of foreign debt, the growth of an unfavourable balance of payments, increasing in monetary supply, galloping inflation and a decrease in foreign reserves – all of which have ended, usually, in political tears. Regardless, such populism has been a feature of virtually every Argentine government since Perón, except for those of Macri and De La Rúa’s administrations. And yet attempts at overall, strategic reform have usually foundered on an all-too-easy reversion to short-term populist politics and free spending.

Then, suddenly, along comes Javier Milei, the leader of La Libertad Avanza (“Liberty Advances”), an outsider to the traditional political tussle between the (conservative) Radicals and the (populist and usually left-wing) Peronists. With his election, political supply seems to catch up at last with public demand, especially of younger, angry, connected voters. He won the November second round of the 2023 election with nearly 56% of the vote over Sergio Massa representing the Perónist Frente Renovador (“Renewal Front”).

Milei campaigned with promises to take a motosierra “chainsaw” to the state. At his inaugural address, he memorably asserted: no hay plata! (‘there is no more money’) for public spending. Over 55% of the electorate voted for Milei, a wildcard candidate and self-described “anarcho-capitalist”, “tantric sex guru”, and a libertarian economist. Little wonder that some Argentines refer to him as El Loco – “The Madman”.

*Special thanks are expressed to Alfonso Prat Guy, Matt Pascall, Lyal White, Daniel Herrero, Domingo Cavallo and Christopher von Tienhoven who assisted with various aspects of the visit. Mills was joined by five-time winner of the Le Mans 24-Hour race, Emanuele Pirro.

[Image: https://www.flickr.com/photos/midianinja/53304116166]

The views of the writers are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend