Beginning in mid-1975, my life evolved into a blur of professional activity. Implausibly, but in line with what I had hoped for, I was a foreign correspondent.

For the Financial Mail I was writing stories about migrant labour on the mines, housing in Soweto and the frustrations of South African shippers in getting products through the port of Lourenco Marques. At Welkom I went underground at a gold mine, surveyed construction of the magnificent dam at Cahora Bassa on the Zambezi River, and interviewed Portugal’s last governor general in Mozambique.

A huge opportunity came unexpectedly when an American diplomat I had recently met said NBC News in London had called, wanting names of Americans who might provide coverage of Mozambique’s independence on June 25th. I phoned London at once and was given a trial, beginning what became a multi-decade career in radio.

Mozambique was my first revolution. It had a promising start, but deeper examination revealed significant shortcomings in what soon became the People’s Republic of Mozambique. The junior officers in charge in Lisbon were intent on getting out of the African colonies as quickly as possible. In the case of Mozambique, a huge undeveloped territory whose coastline was twice the length of California’s, governance was simply handed to the Marxist Front for the Liberation of Mozambique −Frelimo. There were no elections. The insurgents controlled territory in the north, but they never threatened the capital or even the port city of Beira in the middle of the country.

There was excitement on Independence Eve. At midnight in front of the multitude at Machava Stadium, the green and red Portuguese banner − after 400 years − came down for the last time. It was pouring with rain as the thump of celebratory artillery fire echoed in the sky above the seaside capital. While this was going on, I stood in a suburban living room with seasoned correspondents who believed it was better to be close to a telex machine to get your story out than at an actual ceremony.

As bells on the Siemens telex machine rang, indicating that overseas lines were open, the first reporter in the queue sat at the keyboard and began punching his on-scene report onto the yellow tape. During the excitement, Charlie Mohr of the New York Times rushed into the rain to call out the calibre of the thundering weapons. Several correspondents were newly arrived from Vietnam.

With America paying attention to the turmoil in southern Africa, NBC wanted more. I was filing several 30-second radio spots each week. I cleared this additional work with the FM editor, who offered no objection as long as my regular output was not diminished.

My activity turned frenetic with the Soweto uprising in June 1976. For weeks, students had been protesting the Bantu Administration order that Afrikaans be used as a language of instruction. On the morning of the 16th,NBC rang from London to say something was happening in Soweto and could I get out there straight away?

Shel, on vacation from grad school in Michigan, came with me. We climbed into my battered Ford Escort and were off. Luckily, days earlier I had been in Soweto for an FM story and had a general sense of how to get around. I knew that if you turned off the Soweto Highway in advance of the police roadblock you could follow a rutted trail past mine dumps and end up back on the highway inside the township.

We did that and were driving towards the American library in Orlando East. Turning into a side street we were horrified to see students marching in our direction. We quickly reversed, but not before stones were hurled, luckily missing the car.

Arriving at the library, housed in a squat YMCA building, staff members gasped thinking we were crazy, a white couple in the midst of a teeming black settlement where tensions were boiling. They hurried us into the basement for safety. There we heard the loud whir of heavy vehicles and through a crack in a door watched dozens of armed police climbing out of Puma helicopters.

As darkness approached, a staff member asked for my car keys and said he would drive us out of Soweto. We of course agreed. He had us lying on the floor, out of sight while he drove.

The subsequent weeks and months of rioting and repression were intense. I was sent to Cape Town and Port Elizabeth. So great was the demand for reports that the phone from London or New York rang multiple times each day. Stupidly, I kept a bottle of Johnnie Walker next to the phone.

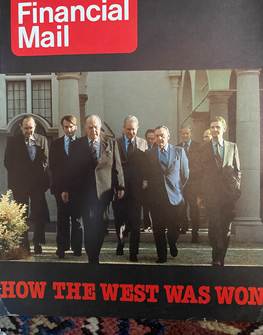

In addition to the South African unrest, the Cubans were in Angola and there was armed conflict throughout the region. I reported from Rhodesia, Zambia, Angola and Namibia. I interviewed Desmond Tutu, Ian Smith, Jonas Savimbi, Beyers Naude, and Pik Botha, among others. I was among the dozen reporters camped on the lawn of the prime minister’s Pretoria residence while Henry Kissinger and John Vorster wrestled over the fate of Rhodesia.

Finally, in mid-1977 I was offered a correspondent’s job in Washington with Voice of America. By then, after three years in parts unknown, I had had enough and wanted out.

I departed Johannesburg in September 1977 three days after liberation activist Steve Biko died in police custody.

What did I learn from this rich, life-changing time in southern Africa? A lot. But perhaps most of all I learned that journalism was an honourable profession, but that to be credible, facts had to be kept separate from opinion. You have to stick to the five w’s of honest reporting − what happened, when was it, where was it, who was there and why did it happen. Or, looked at from a different angle, as a New York Times reporter observed during the 2025 Los Angeles wild fires, “Your job is to take new information, process it, and explain it to your readers.”

*Click on the links to read the first, and second, parts of this series.

[Images: Barry D. Wood]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend