Misinformation is a much used (and misused) phrase these days. It describes the proliferation of false and decontextualised data that skews public perceptions, distorts understanding of important matters and ultimately poisons public debate.

This not only undermines a society’s ability to get to grips with its challenges, but is also likely to accentuate societal fissures. Open societies – those which accept the free flow of ideas and information – can be especially vulnerable to this, and misinformation is a recognisable tool of “grey zone warfare”.

There is no infallible strategy to combat this, certainly not in an age of instant communication, but one favoured approach is to “fact-check”. This is now done by numerous media houses as well as by some specialist bodies. The idea is for a journalist or media monitor to collate contentious claims and to subject them to scrutiny, perhaps by tracing their origins or by consulting experts in the field.

This can be a useful endeavour; if done properly, it can dispel outright falsehoods, show the origins of rumours, and even show how some outlandish ideas have a basis in truth. Hopefully, this can make for a more credible information environment.

Sometimes, though, it can serve to do what it seeks to oppose. A case in point was a recent “Explainer” piece published by Africa Check – the most prominent such body in South Africa, and whose work is often of high quality – on the Expropriation Act. It’s hard to imagine a more contentious domestic issue in the country at the moment. Following President Trump’s intervention, it’s one that’s acquired an international dimension too.

The Expropriation Act

The piece in question used President Trump’s Executive Order as an introductory device, posing the question: “What is the Expropriation Act, and does it allow for what Trump claims?”

The substance of the piece is built around an explanation provided to it by Thomas Karberg of Werksman’s Attorneys. No other source or perspective (other than some extracts from the Act itself) is provided, although seeking the insights of others might have benefited it.

First off, a major premise of the piece was incorrect. “The expropriation of land is not a new phenomenon, nor is it specific to South Africa.” It quotes Karberg in defining what expropriation is. This fails accurately to capture the full scope of the Act’s remit. It is an expropriation act, not a land expropriation act. It sets out the mechanisms for the state to take property, which is explicitly “not limited to land”. In practice, any asset that the state would wish to expropriate – such as company shares, a factory, a coin collection or pension savings – would be subject to this Act. Presenting it in this way, as being by implication solely about land, restates a major misconception about the nature and application of the law.

This itself begins to misdirect understanding.

Just and equitable

Having mischaracterised the Act, the article – it’s not clear whether this comment is drawing from Karberg’s insights – carries on: “The main purpose of the Act is to allow the government to attain ownership of private property for a public purpose or in the public interest, where property owners will receive just and equitable compensation for expropriated land, rather than being paid the market value. This new Act also allows for land to be expropriated without compensation in exceptional cases.”

There’s a jaunty cockiness in this – but it does (inadvertently?) – draw attention to a kernel of the issue: that the Act formalises a system of compensation that gives the state an implied entitlement to a discount on the private property it might wish to take. In fact, it’s commendably honest (aside from the dogged and false focus on land), in that it states baldly: “Property owners will receive just and equitable compensation for expropriated land, rather than being paid the market value.”

It does not favour its readers with an explanation of what “just and equitable” means (“rather” than the market value that might compensate owners for the loss they may suffer). In reality, no one really knows, and the law doesn’t provide much guidance, though the import of this is likely to be that the state is envisaging large discounts for itself. This is hardly uncontentious or without potentially dire consequences, since it poses the threat of a substantial loss to anyone whose property is targeted.

So why is this Act needed? The article correctly points to the disjuncture between the 1975 Act and the Constitution. Karberg refers to a “legal tension” but seems to attribute this to a notion that the previous Act was based on the premise of “willing buyer, willing seller”, which he says, “meant that the government had to pay the market value of the property it was expropriating.”

Non sequitur

This is a non sequitur. The phrase “willing buyer, willing seller” implies a commercial transaction, not a compulsory taking. It’s not particularly relevant to expropriation. Expropriation would likely come into play after a voluntary exchange had failed. The previous Act, like all expropriation legislation, existed to deal with “unwilling” sellers. The 1975 Act required market value, damages for direct loss (such as the loss of business premises) and a solatium. In practice, it didn’t always give those losing property a market-related settlement. This is the risk with the exercise of any power, and especially when the government is callous, incompetent or ideologically fixated. It seems a very bad idea to enshrine greater power in law, given the circumstances currently prevailing.

Indeed, if there was a tension between the “market value” compensation in the 1975 Act and “just and equitable” compensation in the 1996 Constitution, this could have been resolved simply by stating in the Act that market value is what must be considered just and equitable by default, with other factors perhaps used to adjust it. In addition, damages for direct losses should have been included. This would have given investors the security and certainty they would need. Deviations from market value should require additional justification and be applied in limited circumstances which are carefully spelled out and are applied according to clear rules.

It should be pointed out that there is an important political dimension here, which the Explainer ignores. The “willing buyer, willing seller” formulation has long been invoked as a catch-all explanation for the underperformance of land reform – and hence to justify more intrusive state action and encroachment on property rights. This is despite the fact that it’s doubtful in the extreme that this line of argument holds up. The generously monikered High Level Panel on the Assessment of Key Legislation and the Acceleration of Fundamental Change, chaired by former president Kgalema Motlanthe, rejected the view that “the need to pay compensation” had been the most serious problem affecting land reform. Rather, it said, “Other constraints, including increasing evidence of corruption by officials, the diversion of the land reform budget to elites, lack of political will, and lack of training and capacity have proved more serious stumbling blocks to land reform.”

“Nil” compensation

Still, having explained that market value is not necessarily on the table, the Explainer turns to the question of “nil” compensation. This is the totemic issue around which the debate around property rights and expropriation has been framed. Expropriation without Compensation, in other words. While this is perhaps often interpreted as the state seizing something and paying nothing for it, it could in fact take more graduated forms. Indeed, if property is taken at below market value, this represents Expropriation without Compensation, in the sense of “nil” compensation for part of the asset’s value. EWC is in that sense built into the fabric of the Act.

The Act’s definition – as is discussed below – provides another, more expansive ground for compensation-free seizures.

It is nonetheless correct to note that the Act only specifies that “nil” compensation may apply to land. (Other assets seem to be subject to some form of compensation in the event of expropriation, although this could be tokenistic.) The Explainer provides the following three-point schematic of what would be eligible for such a taking:

- The land is unused and kept only for future profit.

- The land belongs to the government, is not being used for its core functions and was obtained at no monetary cost.

- The owner has abandoned the land and is not managing it, even though they could.

This is a reasonable, albeit simplified, view of three of the four grounds listed in the Act. A fourth one refers to situations where “the market value of the land is equivalent to, or less than, the present value of direct state investment or subsidy in the acquisition and beneficial capital improvement of the land.” If this is invoked, it’s likely to kick over a hornet’s nest, not just for past beneficiaries of subsidies, but for any current and future beneficiaries – not least those who might hope to benefit from state support in land-reform endeavours.

“Land [that] is unused and kept only for future profit” is problematic. The actual text of the legislation reads: “Where the land is not being used and the owner’s main purpose is not to develop the land or use it to generate income, but to benefit from appreciation of its market value.” In other words, this places land owned for speculative purposes under the axe.

“Flatly unjust”

Gabriel Crouse, head of IRR Legal, addressed this point in a recent column. He wrote: “Practically, that means land speculation has now been criminalised in SA, at pain of outright confiscation. Buying vacant land to resell at a profit is treated like buying and selling heroin, or illegal weapons. That is flatly unjust. The profit motive is not criminal and cannot justly result in one losing one’s property. The precedent this nil clause sets is also reckless. How does it apply narrowly, for unoccupied second homes and crop-rotating farms, and broadly, for the property rights of anyone who aims to buy now to sell for more later?”

Most concerningly, the Explainer ignores the crucial qualifier: these four conditions are not a closed list. The Act puts its clearly: “It may be just and equitable for nil compensation to be paid where land is expropriated in the public interest, having regard to all relevant circumstances, including but not limited to… ” In practice, there could be a good many other factors that might yield a “nil” compensation price tag. It’s truly remarkable how little this is appreciated, or even acknowledged.

The public interest

The Explainer adds that the law allows land (actually property, once again) to be expropriated “for a public purpose or in the public interest”. This is a breezy formulation whose import is not adequately understood. These are not coterminous ideas, as might be assumed. A “public purpose” is understood to refer to matters relevant to public works and infrastructure – thus, land for infrastructure or for a school or hospital. This is also generally how expropriation powers are understood as an unremarkable part of a state’s arsenal. South Africa’s Act – following its Constitution – extends this to achieving policy goals, “the public interest”.

The Constitution defines the public interest as follows: “The public interest includes the nation’s commitment to land reform, and to reforms to bring about equitable access to all South Africa’s natural resources.” (It follows this by stating that “property is not limited to land”.) Note that the definition is open-ended. It includes “land reform” and “all South Africa’s natural resources”, but is not confined to them. Beware of where this could lead.

Think, for example, about shares in companies that the government deems insufficiently “transformed” or “strategic” (such interventions have been contemplated regarding the private security industry); ownership of private hospitals or schools (given the importance of healthcare and education to the population as a whole); or privately owned artworks that the state might wish to display in a museum for the cultural enrichment of all – or store in the museum’s damp cellar.

This is relevant to the manner in which the application of the Act is envisaged, certainly by some of its proponents. It has been actively promoted as a tool of large-scale redress, not least in the government’s own communications – to say nothing of the manner in which senior figures in the ANC and some other parties have expressed themselves. If, indeed, such concerns are baseless, it would be worth spelling out why.

Custodianship

This introduces one of the key omissions of the piece, and arguably the most serious risk posed by the Act: its definition of expropriation. As the Act puts it: “‘Expropriation’ means the compulsory acquisition of property for a public purpose or in the public interest by an expropriating authority, or an organ of state upon request to an expropriating authority, and ‘expropriate’ has a corresponding meaning.”

The point here is that it formalises the reasoning in the 2013 Constitutional Court case, Agri South Africa v Minister of Minerals and Energy and Another. This, in brief, held that expropriation was defined by taking ownership: property needed to be taken from its owner, and then taken into ownership by the “expropriating authority”. The mere deprivation of property by the state was not expropriation, and therefore no compensation would be due.

The operative concept is custodianship. It means that the state can deprive owners of particular assets (in the “public interest”, presumably), on behalf of “the people of South Africa”, and act as the custodian or overseer of the assets, nominally on their behalf. Technically the state would not own the asset. The former owners would be entitled to nothing, and whether they were entitled to continued access to those assets would depend on whatever permission the state deemed fit to extend.

This is essentially what has happened with mineral and water rights (the 2013 case concerned a mineral right). It is also a model that has been widely proposed for land. In 2014, a Bill named the Preservation and Development of Agricultural Land Framework Bill sought to take all agricultural land into state custodianship. The 2017 Land Audit also recommended “[vesting] land as the common property to the people of South Africa as a whole”. So too did a senior official in the Department of Rural Development and Land Reform in 2019 – remarkably, to an audience at the World Economic Forum in Davos. Whether or not all land or “certain” land should be taken into custodianship was a hotly argued topic during the debate around the proposed constitutional amendment.

Legal basis

Is this still relevant? Absolutely. There remains considerable attraction to the idea of a mass custodial taking of land, and with this law, an important part of the legal basis to accomplish it – free of the costs of compensation – has been put in place.

There will be no land confiscation, reads the Explainer. “Land will not be confiscated because the Act follows the rule of law. Karberg told Africa Check that expropriations would follow a formal legal process, which would allow for adequate notice periods and opportunities to challenge expropriation and the amount of compensation offered. Compensation will either be agreed upon by the state and owner(s) or decided by a court.”

Tediously, one must reiterate that this is not just about land, and to phrase it in these terms is (again) misleading.

Besides, it’s not clear what all this means. Yes, the Act “follows the rule of law” in the sense that it is legislation passed by Parliament – though with an ongoing constitutional challenge – and it provides certain legal protections. That doesn’t make it constitutional, benign or well-advised; confiscations can be legitimised by law.

The concerns though arise from the terms set by that law. How does one challenge the amount of compensation proposed, if market value is rejected (as the Explainer claims)?

In broad terms, expropriation would work as follows: the “expropriating authority” would investigate the property, negotiate for its acquisition with the owner or owners, and issue a notice of intention to expropriate. The owner may object to the expropriation or to anything else; this must be considered, but need not be answered. These steps having been completed, a notice of expropriation is issued, which specifies the date on which ownership and the right to possess the property pass to the expropriating authority. There is no minimum period between the issuing of the notice and the assumption of ownership, so this could happen very rapidly.

The Act does not require an agreement to have been reached between the owner and the state. Nor does it clearly state that a court order on the amount, timing and manner of compensation must have been obtained before the notice of expropriation is served. Prior court orders on other issues, including the validity of the proposed expropriation, may also be needed, but the Act does not provide for this.

Invidious position

True, at this point the owners of targeted owners could appeal this in court, but such a challenge will not necessarily affect the passing of ownership to the state, as a court may well not be able to look at the matter before the specified expropriation date when ownership will automatically be transferred (with registration in the Deeds Office to follow thereafter). In practice, this places property owners in an invidious position: they may initiate a challenge when their property has already been taken, and they have already had to absorb the loss. (The Act also creates some space for delays in payment to be made.) Furthermore, there are significant hurdles to overcome, such as having to prove that compensation is not “just and equitable” – which, as already noted, is a concept without firm definition.

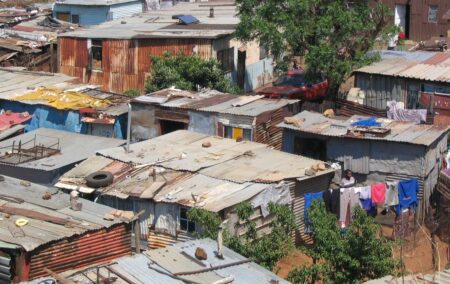

The overall outcome is that unless an owner has deep pockets, the pressure to settle will be powerful. This also means – with some irony, given how this Act had been punted as a mechanism to deal with South Africa’s inequities – that those least able to defend themselves would be those on the less affluent rungs of society. Think less about wine farms or luxury game ranches, and more about peri-urban smallholdings and RDP settlements.

This brings the conversation back to the question of constitutionalism. There were indeed constitutional problems with the previous Act, but a similar issue pops up in the current Act. As the Institute’s submission on the matter stated: “The current Expropriation Act of 1975 is inconsistent with Section 25 and must be replaced. However, the Bill [as it then was] is just as unconstitutional as the present Act.”

Codified in law

These constitutional inconsistencies are now codified in law. Among these is that expropriation may proceed before compensation has been fixed. The Constitution’s wording is clear; expropriation must be “subject to compensation, the amount of which and the time and manner of payment of which have either been agreed to by those affected or decided or approved by a court.”

The new Act turns this on its head, delaying and diluting recourse to and relief from the courts.

The Democratic Alliance, meanwhile, has launched a case at the Constitutional Court against the Act, on procedural grounds regarding its adoption, and on the basis that the Act is “vague and contradictory” in several of its provisions.

All these critiques have been made and discussed in the public domain. None is mentioned in the Explainer, even if only to debunk them.

Justification not comprehension

All in all, it’s hard to see this contribution as providing much of substance in understanding this legislation – to justification, perhaps, but not to comprehension. This is disappointing, given some of the good work that Africa Check does.

It seems, rather, that expositions such as this contribute to polarising the information environment. Dismissing or ignoring concerns and presenting as fact a slanted and (at best) incomplete rendering of complex sets of arguments and information help to legitimate the very misinformation that is today so great a concern.

The Act itself is a threat. It puts expansive powers in the hands of a state for which probity is a rare attribute, and makes these available not only to today’s government, but also those that might come later. There is no guarantee as to how they will use these powers.

South Africa needs an expanding economy, not expanding state discretion. GDP growth has for the past decade scraped by at a derisory level of 1% or so per year. As for the investment to drive it, South Africa manages something in the order of 15% of GDP, while its middle-income peers routinely manage double that. Nothing is a greater disincentive for investment than a threat to the security of property rights. In choosing to enact this law, the prospect of escaping the current malaise has become more remote. That requires serious discussion.

[Image: By Matt-80 – Own work, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=203588]

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend