One reason cited for America’s import tariffs is to stimulate domestic industry. Export controls on advanced technology contradict that theory.

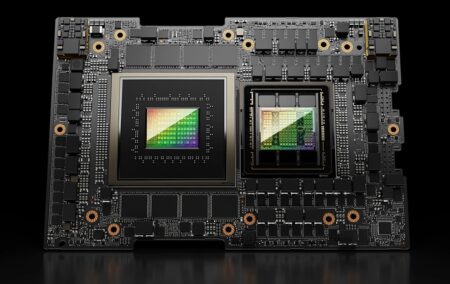

In the wake of a new export restriction on the H20, a class of artificial intelligence (AI) inference chip made by American semiconductor design and supply company Nvidia, the company’s share price fell like a stone.

More powerful processors from Nvidia have for some time been subject to similar export controls, which aim to keep advanced technology out of the hands of China and America’s many other real and perceived enemies.

After the market closed on 15 April, the company issued a statement informing the public that the US government would now require a licence for the export of these chips to China. It said this requirement, to be in force indefinitely, “addresses the risk that the covered products may be used in, or diverted to, a supercomputer in China”.

The company, which was readying a $16 billion order for about 1.3 million H20 chips for Chinese customers, is making provision for a $5.5 billion charge on its balance sheet to account for the setback.

Overnight, from 15 April to 16 April, the stock fell 6.7%, from $112.10 to $104.55, on its way to a bottom of $100.45 later that day, 10.4% off the previous day’s close. At the time of writing, Nvidia was trading 31.3% off its all-time high of $152.16 set as recently as 6 January 2025.

Nvidia’s US rival Advanced Micro Devices plummeted alongside it, reporting that it anticipates that new export restrictions on its MI308 processing unit, aimed at data-centre AI use, will saddle it with $800 million in stranded inventory.

The two chipmakers dragged the rest of the market down, too. The tech-heavy Nasdaq 100 index fell 5.4% overnight from 15 to 16 April, and was last trading 17.1% down from its all-time high set on 19 February 2025.

Sacrifice

Costing your own tech industry billions hardly seems like a good way to support it against foreign rivals, but the sacrifice might be worth it if the export controls keep advanced technology out of the hands of enemy countries who might abuse it.

China, along with 57 other countries (groups D and E on this list), is subject to various sanctions and export controls, for reasons ranging from national security, proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and supporting terrorism, to the arbitrary grudge embargo against Cuba, which hasn’t posed a credible threat to the US for decades.

As I recounted in a column that explained why China would win Trump’s trade war back in February, these embargoes, sanctions and export controls have been notable only for their failure to achieve meaningful change in target countries, or measurable benefits for the US.

While it makes sense to try to prevent the sale of advanced technology to military enemies, long-term export controls on a commercial and geostrategic rival such as China are far more questionable.

Loopholes

A detailed argument in favour of export controls to China, written just before the new H20 export ban was announced, can be found on the website of the Institute for Progress (IFP), a non-partisan think tank focused on innovation policy.

The primary goal is to restrict China’s ability to pursue advanced AI capabilities and build advanced supercomputers. This has a lot more to do with commercial rivalry than with the military threat that China poses to its neighbours, and ultimately to the US.

The IFP’s paper makes clear, however, that export controls often lag technological development by months, or even years, giving target countries plenty of time to stockpile technology products that they expect will become subject to export controls.

The analysis also documents cases in which Chinese companies have already used newly restricted chips to build supercomputers and AI models more powerful than the US would like.

The paper also bemoans the rise of “virtually unchecked AI chip smuggling networks”. It proposes the use of a technological solution to monitoring the ultimate destination of exported chips, by means of a geolocation feature built into the chip itself, but this is not a requirement at present.

Futile

This sounds terribly like the controversy over DVD encryption keys, almost 20 years ago now. DVDs encrypted to foil piracy could be decrypted using a single key, which the members of the Motion Picture Association of America hoped to protect as a trade secret.

It didn’t stay secret, of course. Legal action to supress the publication of the key online failed miserably, and soon people were distributing the key in many forms, including “illegal” prime numbers, T-shirts with the critical part of a free and open source DVD decryption tool, and a 465-stanza poem in haiku form.

On-chip geolocation tools are only as good as the data they’re fed. It would be fairly trivial to defeat such measures simply by obfuscating the potential sources of geolocation data, such as IP addresses, GPS sensors, and network connections.

It is fanciful to believe that targeted export bans will prevent a resourceful country like China with friendly trade links to more than half the world from acquiring the prohibited chips through intermediaries, even if they end up paying a bit of a markup.

Contradiction

The very notion of export controls to limit the capabilities of a commercial rival seems flawed, in fact.

The US government has been imposing import tariffs, for several claimed reasons, one of which is to stimulate the development of domestic manufacturing capabilities.

If that is indeed the effect of more expensive imports, then prohibiting imports altogether would offer an even stronger incentive to develop domestic alternatives to those imports.

Yet the logic that import prohibitions stimulates domestic innovation doesn’t appear to apply to export bans. Somehow, China will sit there counting ceiling tiles, making do with the third-rate chips that US companies do deign to sell to it.

That won’t happen. China has been hard at work expanding its semiconductor fabrication capabilities. Its fabs have yet to reach the advanced process nodes of which companies in Taiwan and the US are capable, but they’re not sitting on their hands, either.

Just two days after Nvidia’s market-shaking announcement, its CEO, Jensen Huang, visited Beijing, where he met with the founder of DeepSeek, a company that shocked the world in February with an AI model that challenged the best in the world, on a budget. Presumably, Huang wasn’t there just to drown his sorrows in rice wine.

Innovation

China has historically been a copier rather than an innovator, more adept at turning niche inventions into mass-market products than at coming up with the inventions in the first place.

However, it is well-placed to change that. It has excellent infrastructure, a large and increasingly prosperous domestic market, a government that generously funds both academia and strategic technology research, and universities that produce some 3.5 million science, technology, engineering and mathematics graduates per year – some of whom are world-class.

The inability to import cutting-edge chips will simply provide added incentive for China to invest in its own innovation capability.

The US would do better to focus on improving its own research, innovation and productivity, instead of trying to play global trade policeman trying to keep its would-be rivals down.

There is no reason to believe China cannot compete with the US in technology innovation, and even outpace it in the foreseeable future. US export controls simply give it more reason to try.

[Image: A Grace Hopper-class graphics and AI processing unit similar to the H20 chips on which the US has imposed new export controls. Source: Nvidia]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend