An enlightening consequence of President Trump’s aggressive tariff campaign is that more people are learning about tariffs and free trade.

Don Trump, the boss of the America First syndicate and the self-declared “Tariff Man”, has given many different reasons why he thinks “tariff” is “the most beautiful word in the dictionary”.

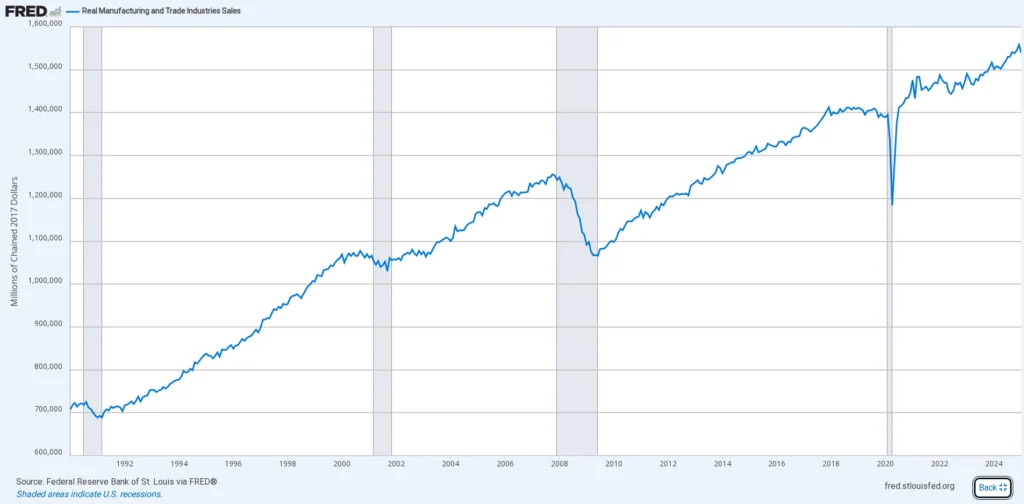

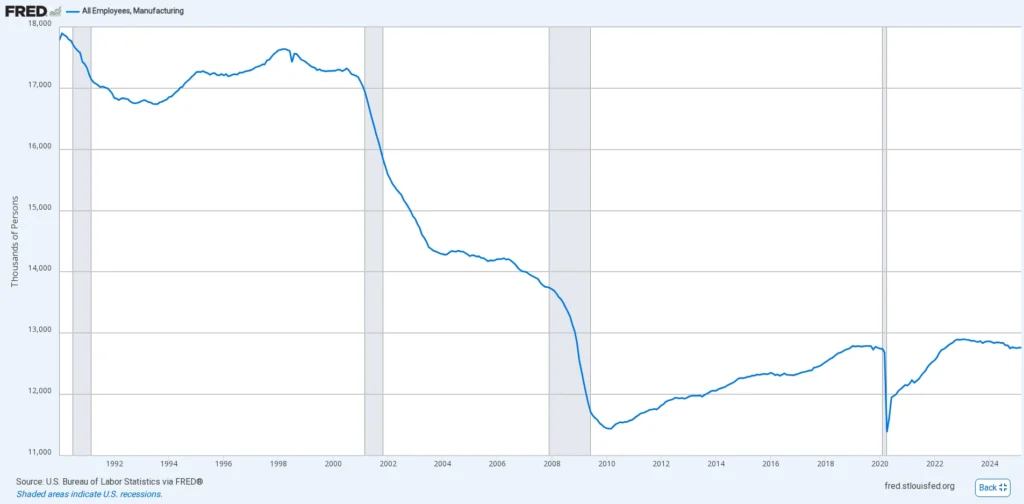

He has promised that tariffs will bring manufacturing jobs back to the US, although there’s nothing wrong with US manufacturing output, manufacturing job numbers have been slowly increasing for fifteen years (since Democratic president Barack Obama’s administration halted the post-dot-com slide that happened on Republican president George W. Bush’s watch), and Trump’s own commerce secretary, Howard Lutnick, admitted that any manufacturing that shifts back to the US because of tariffs would not employ Americans, but would be automated instead.

He has promoted tariffs as a means to rectify trade deficits (when imports exceed exports), because he considers a trade deficit evidence of America being “ripped off”, even though he is also levying them on imports from countries with which the United States runs a trade surplus.

He has claimed tariffs are necessary to strong-arm countries into protecting America’s borders against illegal immigrants and drugs, even though that is quite clearly the job of the US Customs and Border Protection.

Trump has argued that tariffs are necessary to level the playing field against foreign subsidies and other supposed non-trade barriers, including even value-added taxes that do not discriminate on the national origin of products and services for sale to consumers.

He has said Americans need import tariffs because levying “taxes on other countries” will “make Americans rich”, and allow the US to “reduce our taxes and pay down our national debt”, even though tariffs are regressive taxes that fall more heavily on lower-income citizens, and economic models predict that tariffs will reduce real consumption, reduce real GDP, reduce real investment, and reduce employment for Americans.

Most particularly, he has brandished tariffs as “leverage” against enemies and (former) allies alike. That, they are, but they’re less a negotiating instrument than an instrument of extortion. Instead of making mutually beneficial deals between voluntary partners, pre-emptive tariffs extract concessions under duress. America is running a mafia-style protection racket, which is why “Don Trump” is a good way to describe the US president.

Low priority issue

In the past, most Americans knew little, and cared little, about international trade. Since imports account for only a quarter of US GDP, and two thirds of imports into the US are not consumer products, but inputs for US manufacturing companies, foreign trade just isn’t on the radar for most people.

A poll from earlier in 2024 put global trade at the very bottom of a list of 20 policy priorities, with fewer than a third of respondents of either party caring about it. (Reducing the influence of money in politics was near the top of the list, however, which raises the question of how an oligarchy of billionaires with blatant conflicts of interests ended up in charge of the US.)

A 2024 poll by the Cato Institute found that Americans were largely okay with international trade, with 63% favouring increased trade with other countries, and 75% worrying that tariffs would increase prices.

However, in the middle of last year, a Pew Research survey found that a high and rising percentage of Republicans believed the US lost more than it gained from international trade. Democrats, who stereotypically have a worse handle on economics than Republicans, were evenly split on whether trade benefited or harmed the US.

It stands to reason that the poll found a correlation between higher levels of education and more positive assessments of the benefits of global trade. After all, global trade is beneficial almost by definition: if it weren’t so, importers and exporters would not enter into global trade transactions in the first place.

On balance, Americans were not overly hostile to global trade, but few Americans cared much about it, and even fewer were well-informed about it.

Changing public opinion

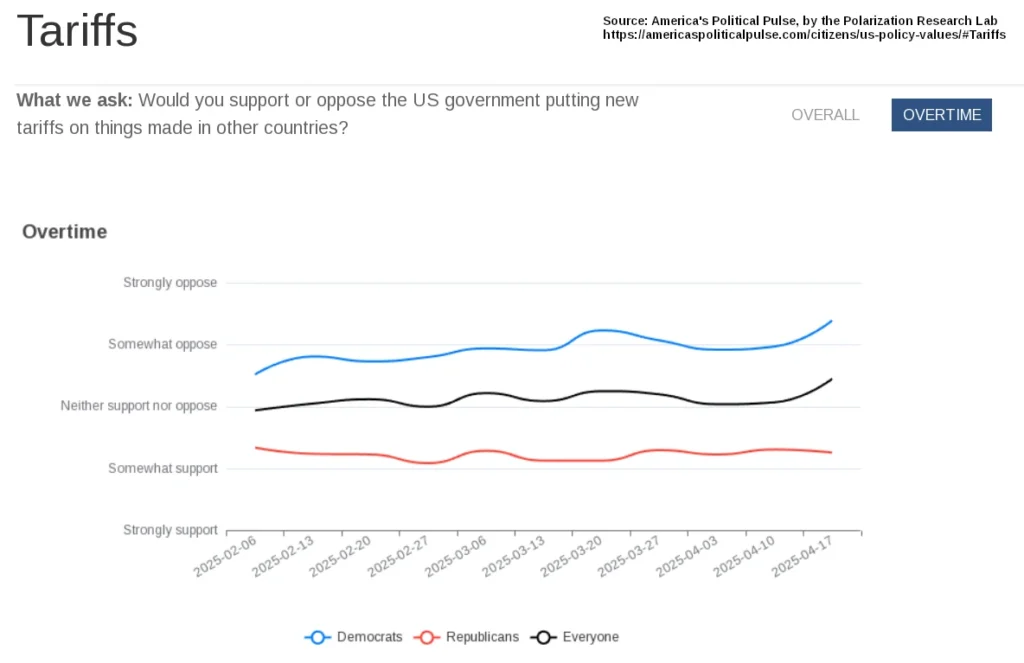

For Republicans, that hasn’t changed. In fact, Republicans are marginally more in favour of tariffs than they were at the start of Trump’s second term.

Democrats, and therefore the average American, have significantly changed their view on tariffs.

Perhaps surprisingly, Democrats started out opposing tariffs by a modest margin in early February 2025, compared to Republicans, who modestly supported them. Democratic opposition has become much stronger in the intervening months, however.

One could attribute this to political partisanship, but of late, both Democrats and Republicans have favoured protectionism. Joe Biden continued the Trump tariffs from the latter’s first term, and even raised them.

The last US president to be openly in favour of free trade was Barack Obama, who in 2015 was granted “Trade Promotion Authority” with 191 Republican votes and only 28 Democratic votes.

Don Trump broke with a tradition of free trade and non-intervention in markets in the Republican Party to raise protectionist tariffs, and Joe Biden followed his lead. If global trade was a low priority for most US voters a year ago, it was at least a bipartisan low priority.

According to a chart published by the Financial Times (paywalled, but reproduced here), liberals (i.e. Democrats) were only slightly more favourably inclined to free trade than conservatives (i.e. Republicans) in the final years of the Biden presidency.

That has changed dramatically. More than twice as many US liberals now “strongly approve” of free trade, and while the approval of conservatives declined, an increase in support for free trade has also been recorded among self-described moderates.

On average, Democrats now fall between “somewhat oppose” and “strongly oppose” on new tariffs.

Economic education

The most likely reason for this is simply education. Since Trump was sworn in for his second term, tariffs have dominated the news cycle. Every month, at the beginning of the month, Google searches for “tariffs” peak as new tariffs take effect or are paused.

Newspapers and media outlets have explained trade tariffs in great detail, including how the burden falls not on exporting countries, but on domestic importers, and how increased costs are passed on to consumers.

They have drawn comparisons with the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, which few people would have heard about before, but which destroyed two thirds of global trade in the early 1930s.

Economists have condemned tariffs virtually unanimously. Well over a thousand credentialled economists signed the Independent Institute’s anti-tariff declaration that argues Trump’s executive actions are based on assertions that misconstrue America’s history, misunderstand its current economic condition, misdiagnose the nature of its economic ills, and repudiate long-standing and widely accepted economic first principles.

Trump has, inadvertently perhaps, forced Americans to become educated about tariffs and trade. Public opinion is forming and changing before our very eyes, in favour of global free trade.

As the consequences of tariffs begin to bite, no doubt greater numbers will become interested in the dynamics of global trade, and discover the benefits of free trade and the high cost of taxing voluntary cross-border trade.

For that, we should thank Don Trump.

[Image: A popular meme circulating on social media, mocking supporters of Donald Trump for their ignorance about trade tariffs.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend