How can anyone be sure their employees are legally of the race and gender they claim to be?

Imagine you’re responsible for human resources at a medium-sized firm. The company employs exactly 49 people.

You didn’t want this job. You studied accounting but partied too hard and didn’t do well enough to land a job at a big company, and now you’re stuck being the bookkeeper for a struggling import business that drop-ships electronic widgets from China at a discount price, because Americans want their own children to work in sweatshops in Ohio instead of importing those widgets from China. And since you handle the pay cheques, the managing director figured you are best placed to shovel the human resources stuff, and you can’t quit because frankly none of this looks particularly scintillating on your CV.

That’s why you drink.

For years, the prospect of hiring just one more employee was not particularly scary, because your employer’s turnover is below the threshold specified in Schedule 4 of the Employment Equity Act of 1998, which is why you’re stuck in this non-airconditioned shed in the industrial area in the first place. At least it’s across the road from a pub.

But now the Employment Equity Amendment Act of 2023 is in force, which removed the exemption for two-bit companies with low turnover, and the manager just told you to find an extra shelf stacker for the bonded warehouse.

That means your company would now employ 50 people and become a “designated employer” for the purposes of the Employment Equity Act.

So now you sit with a problem and it’s only Tuesday.

Not quotas

The Minister of Labour, who has never run a business of any size in his life, has decided on the “numerical targets” (which are definitely not quotas) for your business sector. To meet these targets, your 50th employee should be a woman who is black and has a “physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairment”.

But it is illegal to advertise a job for a black woman. Let alone a crazy black woman.

So you post the job advert, coyly omitting half the actual requirements, and start interviewing.

In walks Joe. He’s a middle-aged bloke who seems capable of stacking shelves.

A sophisticated battery of tests you designed yourself determines that Joe can count at least as high as 20, and can read a clock to determine when tea-breaks start and end. On merit, he clearly qualifies.

There’s just one problem. Well, two, really. Three, even.

He has a beard. He is as pale as a Romantic poet. And he looks quite sane.

Black

This won’t do. The “numerical targets” are clear. Joe simply can’t have the job.

Sensing that something is amiss, he pipes up.

“I’m black, you know. I’m from a long line of people blacker than the ace of spades,” he says. “I’m not sure why I look like Lord Byron, but my dearly departed mom told me not to worry my pretty little head about it.”

“You’re not black,” you reply, confident in your diagnosis of Joe’s racial condition.

“Prove me wrong,” he rebuts.

Well, now you’re in a pickle. Although the Employment Equity Act says that “‘black people’ is a generic term which means Africans, Coloureds and Indians,” it doesn’t actually offer a legal definition of what it means to be African, Coloured or Indian.

That’s because there is no legal definition of what it means to be African, Coloured or Indian (or white, for that matter).

If someone says they’re black, then that’s what they are, for the purposes of South Africa’s 142 laws that rely, one way or another, on a person’s race. The Population Registration Act of 1950 that formally classified people according to their race was repealed, so on what legal grounds would you propose to dispute Joe’s claim?

There’s nothing on his identity card that confirms his race. And even if there is legal precedent for “deviations” from “numerical targets” (which is why courts have not held those targets to be “quotas”, which would be unlawful), the Employment Equity Act does require human resource managers to report on the demographic composition of their company’s workforce, or face a fine of 10% of their revenue. So what do you put on Joe’s employment equity form?

Human resource manager might not be your primary job description, but 10% of your company’s revenue, paltry though it is, would still bankrupt your employer and cost you your miserable job.

Female

At least one can prove someone’s gender by means of their identity number. If the seventh digit is 0 to 4, that means the person is officially a woman, and if it is 5 to 9, that means the person is officially a man.

The seventh digit of Joe’s identity number is a 5, so at least you can disqualify him on the grounds that you need to employ a woman.

“Also, I’m a woman,” says Joe. “Joe is short for Josephine.”

You’re no expert in labour law, but you’re pretty sure you can’t ask Joe to drop his trousers so you can examine his naughty bits. You’d be inviting a lawsuit, which would also bankrupt your employer and cost you your miserable job.

If someone has to take the fall for Joe’s apparent fraud, let it be the apartheid-era obstetrician who knew no better and sexed infant Joe based only on the appearance of his external genitalia. That may not be a sound basis for determining a person’s sex (or gender, for that matter), but that’s not your fault.

Hired

“Fine,” you tell Joe. “You’re hired.”

You grab the employment equity form, and start inking in the details.

Race? Black. Check.

Gender? Female. Check.

Mental disability?

You look over at the pale, bearded chap across your desk.

Crazy. Check.

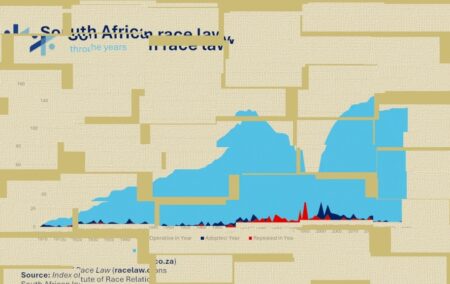

[Image: Race Law Illustraton.webp – CAPTION: Illustration by the author, based on the chart available at the Race Law initiative of the Institute of Race Relations.]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend.