Recently, against the background of a coalition government and with the Democratic Alliance polling on a level with the ANC, there has been some tentative discussion about the prospects of a DA-led government. Journalist Bhekisisa Mncube took this in the inevitable – inevitable for South African public discourse – manner of refracting this through the prism of race.

“Is South Africa ready for a white president?” he asks.

“I doubt it,” comes his reply. For Mncube, there are relatively straight lines between the DA and “white”, and the ANC and its offshoots and “black”. The thrust of his argument is that if the DA manages to take the lead in forming a future government, that will mean a DA president, and “implicitly a white man”.

Although not eloquently argued, his article raises one of the perennial talking points of South African politics. That point is, given the role that race and race nationalism have played in the country’s history, ‘Does a political party need a black leader to be successful’? Mncube ramps this up a notch, suggesting that a white president would be unacceptable to most of the population.

In this, he probably reflects a large volume of conventional wisdom.

Indeed, he could call upon some polling to support this. In September last year, the Social Research Foundation asked: “Whichever party governs South Africa, it must have a black leader to be a success. Do you agree or disagree with this statement?”

A little more than half of respondents, 54,1%, agreed (“strongly” or “somewhat”). A rather lower proportion, 42.7%, disagreed. This matches fairly closely what the SRF found in a similar enquiry in 2022.

Weight of opinion

Responses were split across racial lines, with close to two thirds (64%) of Africans responding affirmatively, and a third (33%) negatively. Among racial minorities, the weight of opinion was strongly in the other direction. Some 67% of Indian respondents, 70% of white people and a whopping 88% of Coloured people disagreed.

On the face of it, this supports Mncube’s contention. Not only does an overall majority of the population believe that a black – read, African – leader is necessary for political success, but the racial divergence in responses lends credence to the contention that racial identity remains the key driver of South African politics. Africans, by this reasoning, would be reluctant to surrender leadership of society. The country’s racial minorities, by contrast, would see in this question their effective exclusion from such roles.

From this perspective, the idea of a white president would be a contentious one.

Looking at the question, however, one would need to ask whether the respondents were expressing an analysis or a preference. In other words, to what extent do these results reflect a hard rejection of a possible white candidate (or for that matter, an Indian or Coloured one), or a scepticism that he or she could gain the necessary traction.

These things are difficult to tease apart. Some South Africans may simply be racial nationalists, and some may believe their fellow citizens to be. Or there may be a sense that there is something natural – an axiom of South African politics – about South Africa being headed by an African.

The latter point finds some support in the conduct of the ANC over the years. It’s often forgotten that the ANC has a history of segregation of its own – a point it doesn’t dwell on in much detail these days. Until the late 1960s, only Africans were accepted into its ranks (members of other racial groups needed to join separate congresses, or the SA Communist Party), and only in the 1980s, into its leadership. Despite the considerable standing and popularity of some of its minority members, such as Trevor Manuel (who garnered the largest number of votes for the party’s National Executive Committee at its 2002 Conference), none has ever been mentioned as a serious contender for the leadership of the party.

Still, there is reason to question whether all this does indeed mean a hard ‘No’ to a white president.

Not unbridgeable

The overall split in opinion is not unbridgeable. There is also a good deal of polling that demonstrates that racial divisions are not the all-consuming and existential issue that they are sometimes made out to be.

The IRR’s polling, for example, shows that between seven and eight out of ten South Africans hold accommodating views of their peers from other races, specifically agreeing that the different races need one another for progress. The Institute for Justice and Reconciliation (IJR) has shown repeatedly that South Africans have a widespread shared commitment to an inclusive South African identity, and while there is recognition of the society being a divided one, this is not for the most part one of race, but far more a division built around socio-economic status.

Moreover, an enormous body of polling over the years has shown that the primary concern of South Africans is their material wellbeing. Employment is invariably the most pressing concern, followed by such issues as corruption, crime, healthcare and education. These are practical, quality-of-life issues. Matters relating to esteem or even to redressing real past abuses (but with doubtful value in improving people’s circumstances) such as land reform invariably poll poorly.

That being said, South Africa is a low-trust society. Ascribe this to its history, to a violent and insecure society, or to inept and dishonest governance. IJR polling has found that a minority of South Africans trust any group outside their families (and in 2023, only 45% indicated that they could trust their relatives). In 2023, some 36% expressed trust in their neighbours, 32% in people of different sexual orientations, 32% in people speaking other languages, 29% in their colleagues, 27% in people from other races, and 21% in migrants from elsewhere in Africa. The import of this is that distrust across racial lines – while real – is part of a larger problem of societal distrust. The kernel of the issue is that South Africans don’t trust one another, not that black and white South Africans don’t trust one another.

Worthy of trust

Trust is a general problem for South African governance and the endurance of its democracy. The solutions will be to elevate the quality of governance to make it worthy of trust, and to deliver on those material demands. Get growth growing, get companies hiring, and create the revenue for better redistributive endeavours. It’s hard to see much resistance to this, irrespective of the racial or indeed the political identity of the leader presiding over this.

So, is South Africa ready for a white president? Not in the sense that it is expected, or within a readily accessible frame of reference for most of its people. The very idea has been painted as something sinister – a narrative to which Mncube’s piece makes a contribution. (And it’s also a reason why his equation of DA with ‘white’ is lazy thinking – the DA is by all accounts the most multi-racial party in South Africa’s history, and because it’s wary of the “white party” line, it is by no means obvious that the party would choose a white person as a presidential candidate.)

But however such a candidate might find his or her way into the Presidency, and whatever party that candidate might represent, he or she would be something novel. It would be jarring.

But South Africa can also look at plenty of other societies in which culturally “unanticipated” candidates have made it to the top office. Alberto Fujimori, of Japanese descent, became president of Peru. Guy Scott took over as President of Zambia, becoming the white President in an almost entirely black population. Rishi Sunak, of Indian heritage and a Hindu, became the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom – a historically white country with a state religion in which the Prime Minister actually plays a role. Barack Obama, for all the dark muttering about how systemically racist the US was, comfortably won elections twice.

And then there has been the rise of women heads of state, even in some very conservative and masculine jurisdictions – forget Margaret Thatcher, Theresa May or Liz Truss (better forgotten anyway) in the UK, try Benazir Bhutto in Pakistan.

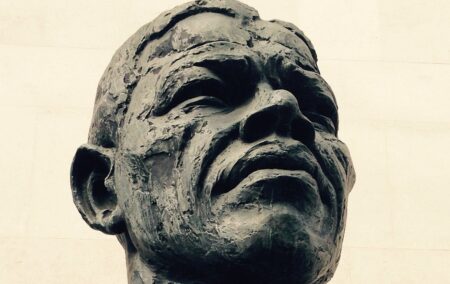

Sincerely loved

Or for that matter, consider South Africa’s own history. In the later 1980s, who might have predicted that a long-term political prisoner would ascend to the presidency – and become sincerely loved by the same white population that five or six years previously had viewed him as the very avatar of the threat to their society and way of life? Or that in 2024, the ANC and the DA might be able to conclude a coalition agreement, fragile and conflicted as it has been shown to be.

There is something to learn in all this, and especially in South Africa’s own experience. Most things look impossible when first raised, unlikely before they happen, novel when they do, and unremarkable in hindsight. A white president? Who knows? Stranger things have happened, and have been regarded as entirely normal afterwards.

[Image: photosforyou from Pixabay]

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend