Proposed banking deregulation in the United States has media panicked, but it’s actually great news. Here’s why.

“US watchdogs are reportedly planning to slash capital rules for banks designed to prevent another 2008-style crash, as Donald Trump’s deregulation drive opens the door to the biggest rollback of post-crisis protections in more than a decade,” reports The Guardian.

In the third paragraph, it cites a source: “Regulators are expected to put forward the proposals this summer, aimed at cutting the supplementary leverage ratio that requires big banks to hold high-quality capital against risky assets including loans and derivatives, according to the Financial Times, which cited unnamed sources.”

Well, it’s the FT, so it must be credible, right? Besides, it’s behind a paywall, so who will even check?

The thing is, the FT headline says “FCA to ease rules restricting mortgage lending”. And that’s curious.

Curiosity

Curious, because restrictions on mortgage lending and capital rules are not the same thing. The former is about how much risk banks are permitted to take when lending, and the latter is about how much cash banks are required to hold in reserve against loans and derivatives.

And curious too, because the FCA is either the Ferrari Club of America, which has no authority over banks, or the Financial Conduct Authority, which does have authority over banks, but not in the United States.

The FT article was published more than two months ago. It reports on mortgage lending restrictions in the United Kingdom, where the FCA does have authority. The intention there is to relax rules requiring banks to stress-test whether prospective customers can afford higher interest rates, in the hope that it will stimulate mortage lending.

While that is also good news (with some caveats), the article doesn’t mention US banking regulation at all (as this archived copy of the article shows). So why is The Grauniad so unstrung?

It seems in their haste to whip up panic over a new financial crisis, they got their banking functions, banking regulators, and banking countries all mixed up.

It is, however, true that US regulators are expected to relax capital adequacy requirements for banks, especially against relatively safe assets such as US Treasury bonds. You’ll just have to read a different newspaper to get the actual news. Let’s try Reuters.

That’s better. According to the Reuters version, relaxing the “supplementary leverage rule” imposed after the global financial crisis is high on the agenda for US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent. Not only does it unnecessarily apply to very safe assets, like US Treasuries, but over time, it has put restraints on lending, especially among smaller banks, who are held to the same standard as large financial institutions.

Blaming bankers

The reason this is good news is that the inadequacy of banking regulation was not the cause of the global financial crisis that began in 2007. It has been widely fashionable, among journalists, some market analysts, politicians on both sides of the aisle, world leaders, and even some bankers themselves, to blame bankers for the crisis.

What was actually broken was the incentive structure and legal obligations placed on banks. The most obvious incentive was cheap money, which inevitably inflates asset bubbles and stimulates risky financial transactions.

Less obvious were the laws that required banks to forgo certain risk assessment methods and required banks to issue sub-prime loans against their better judgment.

Sub-prime lending was blamed on “greedy bankers”, instead of on the Community Reinvestment Act and other laws and incentives that required and rewarded sub-prime lending.

These laws and incentives were promoted by politicians like the then ranking Democrat on the House Financial Services Committee, Barney Frank. He was the one who denied a crisis was brewing in the housing market, and he was the one who wanted to “roll the dice a little bit more in this situation towards subsidised housing”.

Dominoes

The collapse started with two government-owned behemoths in the US, Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, which existed for the sole purpose of buying sub-prime mortgages from originating banks who didn’t want to be saddled with dodgy debt.

This amounted to government guarantees of the debt. That low-quality debt was then repacked in complicated derivatives to spread the risk and sold on to major financial institutions. Again, “greedy bankers” were blamed for trying to sell on their risk.

By the time it became clear that a lot of those sub-prime loans were never going to be repaid, because Barney Frank rolled the dice once too often, nobody knew where the toxic credit had landed, which made all those derivatives toxic, and the dominoes started falling.

For a longer explanation of why the 2007 banking crisis was caused not by the banks, but by their governments (the US government first among them), this column I wrote in 2010 is well worth re-reading. History rhymes a lot, after all.

(And for a more birds-eye view of the political economy surrounding the financial crisis, which was predicted in 2001 by libertarian congressman Ron Paul, just like libertarian economist Ludwig von Mises predicted the crash of 1929 and the Great Depression, try this column from 2011. Unfortunately, the charts and videos have vanished over time, but the text remains worth another read.)

Blame regulators

The problem with banking risk is not that bankers take reckless risk because they’re greedy. It goes without saying that bankers are “greedy”. Greed is just another word for self-interest and profit maximisation, traits which sound economic policy ought to assume in everyone.

The problem is that they take reckless risks because governments encourage, require and incentivise them to do so. If bankers weren’t sure that their bad risks would be covered by the government using taxpayer money, maybe they’d think twice about taking those risks.

If banking customers weren’t guaranteed that their deposits would be repaid by the government in case of banking failure, maybe they’d be a bit more selective about who they entrust their money to. (As an aside, there’s a middle way between public deposit insurance and no insurance at all, and that is to require that depositors buy private insurance. That would give deposit insurance companies, competing for customers, a profit motive to oversee banks and the risks they take, obviating the need for burdensome government regulation.)

Private profit, socialised risk

Banking regulation ought to be really simple: private profits should not be based on socialised risks. If they are, you get the banking oligarchy we have today.

You get excessive risk, and you get ever-more burdensome rules to try to regulate that risk away. And the more risk you regulate away, the less profitable banks become, the less likely they are to lend, the less capital is available to the market, and the less investment and consumer spending happens.

Whereas banking the world over was in the process of becoming even more heavily regulated and risk-restricted, in a process sinisterly known as the “Basel III endgame”, banking industry representatives have called the pending reforms under the Trump administration “overdue and welcome”.

It remains to be seen whether Bessent and the other players in bank regulation are willing to go far enough to finally wean banks off taxpayer bailouts and the “too big to fail” doctrine. They are highly unlikely to go as far as Ron Paul would have like them to go, and that is to end the Fed and return entirely to private issuance of money, without government control over interest rates.

Trump’s insistence that the Federal Reserve lower fund rates, even though the Federal Open Market Committee is anxious about both inflation and unemployment – the twin mandates of the US central bank – doesn’t suggest that his grasp of macro-economics is up to the standard actual free market advocates would like.

After all, cheap credit was at the root of the housing market bubble, and the dot com bubble before it, and every other bubble that burst, as bubbles must.

That’s also where the caveat about the UK’s plan to ease lending restrictions comes in. Merely relaxing lending rules will increase the risks banks can take, without changing any of the underlying incentives. If banks can still rely on the knowledge that the government will bail them out when push comes to shove, they’ll still take excessive risks.

Contagion

Trump’s commitment to “cut 10 regulations for every new one”, which the banking sector immediately saw as an opportunity, has had ripple effects.

As The Grauniad put it: “Prospects of a deregulation drive have sparked concerns in some corners of the City of London that the UK could fall behind and become uncompetitive compared with US peers, because of stricter regulation.”

The regulatory changes mooted in the UK are less far-reaching than those in the US. They merely make the mandatory credit risk assessment a little less onerous, which will make banks more likely to issue mortgages and business loans.

It is, however, a step in the right direction.

Meanwhile, the European Central Bank has also launched a “task force” that has been instructed to concoct ways of simplifying banking rules in Europe. The ECB doesn’t have the power to actually do so, but it can advise the European legislators on how to proceed.

All this suggests the dawn of a new era of competitive deregulation.

Although much can go wrong with deregulation if policymakers don’t carefully weigh the impact of all incentives, restrictions and obligations – “that which is seen, and that which is not seen,” to quote Frédéric Bastiat – that the era of the ever-growing regulatory burden appears to be over is excellent news.

PS. I’ll leave it to the MAGA fans in the comments to square this opinion with my supposed Trump Derangement Syndrome.

The views of the writers are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend

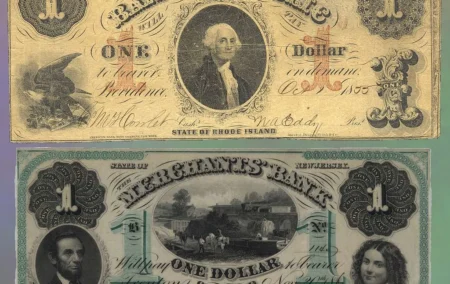

Image: Two examples of currency issued by private banks, from 1861 and 1863, respectively. They constituted a promise that the bank would pay the bearer the value of one dollar in gold, and relied entirely on the trust merchants had in the soundness of the issuing bank. Public domain images.