One of the common criticisms “of” (a strawman of) the Index of Race Law is that most if not all of the post-1994 race laws it records are constitutional and must therefore not be recorded.

This puzzling submission was repeated last week by News24 in a vibe-check that once again affirmed the validity and accuracy of the Index.

The claim also often comes alongside a call to action, that if the Index of Race Law “objects” (it does not) to these race laws, rather than presenting them, the laws should be challenged in court.

The thing to understand upfront is that those who make both these submissions know exactly what they are doing. They are not misguided or ill-informed, but malicious.

The Constitution is a race law

In the first place, if the Index did not exclusively track Acts of Parliament, the Constitution itself would have been recorded as a race law.

The supporters of race law believe the Constitution allows a lot more racialisation of our society than it truly does, but in fact it is only really a race law to the degree that it requires demographic (racial) representivity in the composition of the judiciary (section 174(2)), Chapter 9 commissions (section 193(2)), and the public service (section 195(1)(i)). Most post-1994 race laws are traced back to section 195(1)(i).

Nonetheless, various other provisions have also been racially construed and implemented, primarily (and most perversely) the right to equality stated in section 9(2) of the Constitution.

From a more normative perspective, it is highly opportunistic to appeal to the Constitution, as a race law itself, to nullify criticism of race law. It implies that if Hitler (reject Godwin’s law) had simply adopted a Nazi Constitution in Germany and codified the Holocaust, all criticisms of discrimination against the Jews would have been nullified because “it’s constitutional.” It implies that if the Americans had simply made explicit allowance for slavery in the US Constitution, the whole abolitionist movement would have lost its legitimacy because “it’s constitutional.”

Constitutionality is not salient, especially if the Constitution itself is guilty of the very thing being complained of.

But quite aside from this: the Index of Race Law is not a normative instrument and therefore the question of constitutionality does not arise.

The Index of Race Law is not a record of constitutional or unconstitutional laws, but a record of race laws.

If this were an index of corporate law, it would not exclude the various laws relating to corporate and juristic persons simply because those laws are constitutional.

The mere fact, to take another example, that the Constitution allows Parliament to adopt laws on insolvency, does not mean that those insolvency laws cease being insolvency laws simply because they are constitutional.

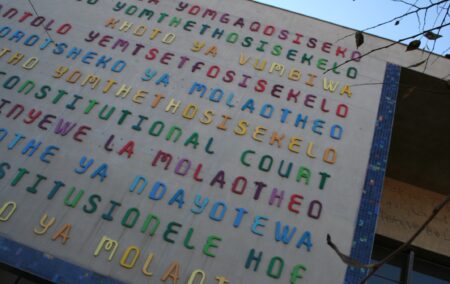

The Constitutional Court makes race laws

In the second place, the critics know very well that the Constitutional Court has, since its establishment in the 1990s, been an eager defender and solidifier of race laws. It “makes” race law whenever it sets judicial precedent that recognises any legal relevancy for inborn skin-colour.

To tell opponents of race law today to challenge those laws in court would have been akin to asking black South Africans during Apartheid to challenge race laws in court.

Our courts need to clean house and do a lot of introspection before this becomes a possibility.

In particular, the Constitutional Court precedent of Van Heerden would need to be reversed, as that judgment effectively closed the door to challenging racialised legislation. In practice, Van Heerden held that if a racially discriminatory law is intended to redress past injustice, it is more or less unassailable.

Intention cannot be challenged in our courts in any substantive way. In the infamous Agri SA judgment, the Constitutional Court made this clear by imputing – without being prompted – the most noble of intentions to our political elite with their nationalisation of minerals. The Court, specifically Chief Justice Mogoeng, spent a lot of time in unjudicial fashion praising Parliament for adopting the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act.

To complete the circle, the Constitutional Court in its Glenister III judgment laid into the litigant, Bob Glenister, who attempted to argue – with evidence – that the government was essentially corrupt and untrustworthy and therefore cannot be constitutionally allowed to be responsible for combating corruption within its own structures. The majority of the bench labelled these submissions as “scandalous, vexatious, and irrelevant,” calling it “reckless and odious political posturing” and “propaganda.”

In other words, not only will the highest courts in the country assume the most noble of intentions from South Africa’s august and selfless politicians, but an attempt to call the nobility of the kingly class into question will be viciously rejected. How, then, can one ever hope to clear the Constitutional Court’s standard of only racially discriminatory laws not intended to redress past injustice could be unconstitutional?

It is virtually impossible, which is why most anti-race law litigation today occurs at the margins rather than striking at the heart of the legislation in question.

So, no, “go to court” is a silly idea in the context of the war against legalised racial discrimination.

There will always be litigation, but the judiciary cannot be regarded as the only legitimate forum for the cause of constitutional non-racialism.

But, to a large degree, this is beside the point, because the Index of Race Law does not object to or evaluate the desirability of race law – it only and exclusively tracks and records it.

News24’s latest “vibe-check”

With all this in mind, we can turn to the News24 vibe-check on the Index.

The framing of the report is, quite evidently, opportunistic, but it does represent some welcome progress in the debate on race law.

Whereas before, so-called journalists and public commentators attempted in bizarre fashion to maintain that the laws identified in the Index are not in fact race laws, now there is at least a grumbling admission that they are in fact race laws – but they are “constitutional” race laws!

This is a more defensible position for those who support the state’s transformania, and at long last moves the discourse out of the arena of facts (the law is racial) versus feelings (the law is well-intended), and into the arena of a difference of opinion.

Indeed, each of the laws identified by News24 (the Employment Equity Act, National Qualifications Framework Act, National Heritage Resources Act, Housing Act, and National Arts Council Act) are admitted to be racial by the vibe-checker, Andrew Thompson, though he is reluctant to write precisely those words.

For those still in the dark

The Index of Race Law tracks laws (only Acts of Parliament at this stage) that satisfy the following query:

Does the Act recognise a pre-existing (statutory/judicial) legal relevance of someone’s race, skin-colour, or ethnicity?

Does the Act establish new legal relevance for someone’s race, skin-colour, or ethnicity?

Does the Act allow a state functionary – an official or minister, for example – to do anything that makes someone’s race, skin-colour, or ethnicity legally relevant?

If the answer to any one of these questions is “yes,” the Act in question is a race law.

To perhaps oversimplify, the Index asks: does or could skin-colour matter at all to whatever this law is concerned with?

Under common law (the baseline), a person’s race is no factor in determining that person’s rights, obligations, advantages, disadvantages, interests, or activity in law. But a statute (legislation) might override the common law and in fact make skin-colour or ethnicity such a factor.

This is what the Index tracks.

The Index is the latest in almost a century of work by the Institute of Race Relations to ensure South Africans and foreigners are aware of the various laws that take a person’s inborn melanin content – something over which they have no control – and turn it into something advantageous or disadvantageous.

This enterprise makes a lot of people uncomfortable, and rather than criticise the factual record, the best way for them to move beyond that discomfort is to lobby Parliament to adopt the IRR’s No More Race Laws Bill.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend