Constitutions are not sacred texts: they are tools to recognise and entrench liberty, limit state power, and ensure basic justice. But a constitution can fail at this purpose, and in South Africa – particularly in the context of racial victimisation and property deprivation – it would be difficult to argue that it is not failing.

The year 2014 was the first for me of being an activist for liberty. To mark the occasion, I had to travel to Ibadan, Nigeria, to participate in an African Students For Liberty (ASFL) leadership retreat as ASFL’s local coordinator at the University of Pretoria.

As a naïve 19-year-old, I remember asking my more experienced, wiser colleagues who had been active in Nigeria for several years what the Nigerian Constitution says about the federal division of power in that country.

Rather than giving me the answer of an analyst or a jurist, everyone around the table basically just laughed at the question. The implication, which they went on to explain, was that it does not really matter what the Nigerian Constitution says about federalism or anything else. The provisions of that constitution are, at best, guidance where there exists political doubt, but probably mostly dead letter that have to play second fiddle to raw political reality.

The contract

Modern constitutional democracy rests on a simple bargain: the state protects individual liberty in return for individuals accepting the state’s authority. The result? Public order.

Part of this order is that individuals have to tolerate one another’s eccentricities.

Jews in the United States have to accept a neo-Nazi or pro-Hamas rally at a university, because the Jews are in turn allowed to hold a pro-Israel or Zionist rally. Satanists have to accept that Christians can build churches in their neighbourhoods because Christians also have to accept that Satanists can build their own temples in turn.

This system of democratic legitimacy holds because it strictly observes equality at law within the paradigm of a strictly limited government. And to safeguard the system, constitutions are designed with various institutional checks and balances.

South Africa’s constitutional order makes this very same promise, with little follow-through.

Make no mistake about this uncomfortable legal fact about 2025 South Africa: there are things that black people are legally allowed to do because they are black, that white people are not allowed to do because they are white. This is de jure, legal reality.

Hate speech: Gouws versus Malema

Renaldo Gouws is the walking, talking embodiment of this reality.

Julius Malema, one of the most powerful and influential South African politicians of the past decade, has repeatedly chanted “Kill the Boer” and directly incited racial violence.

Gouws, seeking to point out the absurdity of what we were allowing, in an act of protest (rather than genuine reflection on racial affairs) made a video wherein he mockingly chanted about killing black people.

The response? Legal and social crucifixion for Gouws.

Malema giggled, untouched for his sincere racial threats, while Gouws faced all Hell’s fury for pointing out the double standard that ironically saw him lose his job and be persecuted by the Human Rights Commission.

Professor Koos Malan and Dr Willem Gravett have already decisively dealt with how the courts – from the High Court, through the Supreme Court of Appeal, to the Constitutional Court – thoroughly delegitimised themselves with their shameful performance in the “Kill the Boer” saga. The archetypical “last line of defence” in constitutional design – the judiciary – failed in epic fashion to resolve a significant social dispute.

This was not just a failure in court with the losers now crying that they did not win their case. No. As I will show, there is a systemic failure at play.

Because, firstly, in this saga the performance of the courts was not the only failure of the constitutional order.

A head of state in a democracy is meant to be a unifying figure that represents the whole population rather than specific constituencies, as Members of Parliament and other representatives do.

The President of South Africa is constitutionally meant to be the national representative and therefore must, to some degree, stand aloof from social disputes. This office is meant to be a calming and harmonising figure in society.

After the courts dishonoured themselves in the Kill the Boer matter, the civil rights group, AfriForum, sent a letter to Cyril Ramaphosa requesting simply his condemnation of Malema’s chant.

The presidential office responded immediately, saying that Ramaphosa will under no circumstances condemn it. A few short weeks thereafter, Ramaphosa went to the White House and told President Donald Trump that he does, in fact condemn the chanting of Kill the Boer. And then, days later, once he was back from the United States, he again reiterated that he does not condemn Kill the Boer.

This is not evidence of a head of state who represents all “his” people. This is an opportunistic charlatan playing political games to try and score points against a segment of the population he is meant to represent. Gracing him with the title of “President” is something I personally try to avoid.

Parliament, of course, as another constitutional institution beside the presidency and courts, has also thoroughly failed to bring order to chaos.

Malema and his party have broken the rules of Parliament repeatedly, necessitating security intervention on multiple occasions. And through it all, he has been allowed to remain a member in good standing.

Malema’s chanting of Kill the Boer would have been a bitter, though acceptable pill to swallow, had the right to reciprocate been respected. That those who might want to (the number of which rounds to about zero), could chant “Kill the Blacks,” or that those like Gouws who would use the mechanism to make a perfectly valid and non-racial point, would be allowed to do so.

Alas, no.

Land reform: The original sinners

The political class – in the words of people like Ramaphosa himself, Deputy President Paul Mashatile, former justice minister and current Minister of International Relations and Cooperation Roland Lamola, Julius Malema, and countless others – has made it crystal clear that the Expropriation Act of 2024 will be wielded as a tool of racial retribution.

This is by now public record that nobody in the governing African National Congress (ANC) would seriously deny.

There are various junctures at which abusive legislation like the Expropriation Act should have been stopped by the constitutional architecture:

The people who wrote the bill – state legislative drafters – should have had basic respect for the Constitution trained into them and engrained in their thinking. They should never have written the words that today appear in the Act.

The people who sponsored the bill – successive public works ministers across three presidential administrations (2008-2024) – swore oaths to uphold the Constitution. They should never have introduced the bill.

The oath of office binds the character and morality of a given official up in adhering to the Constitution. In democratic theory, the public implicitly regards the oath as a tangible and binding safeguard for their interests.

Every member of the parliamentary committee charged with reviewing the bill swore the same oath.

They should have peer-reviewed their errant colleagues, the ministers, and rejected the bill. This should have happened particularly after thousands of written submissions, over multiple years and across three separate parliaments, pointed out precisely – in belaboured detail – how the bill was unconstitutional.

State and parliamentary legal advisers, who advised the committee during the public participation and debating process, should have been engrained with a culture of constitutionalism. They should have advised the committee from the start that the bill did not meet constitutional muster. Instead, they came up with clever contrivances to sidestep constitutional safeguards.

Parliament itself, in plenary session, should have soundly voted down the bill. If the popular National Assembly failed to do this, at least the more dispassionate National Council of Provinces should have exercised its check against the lower house. Neither happened.

In the particularly British tradition of democracy that South Africa has inherited, Parliament is the main failsafe. It is the people’s guardian. It was established as a check on the power of the sovereign: the voice and sword of the common man against state predation.

The President, as head of state, after the bill arrived on his desk, should immediately have referred it back to Parliament to consider the serious outstanding constitutional issues. And if Parliament still insisted on adopting it, the President should have referred it to the Constitutional Court. Neither happened.

The last line of defence here, again, is the courts. But given how the Constitutional Court chipped away at the property provision in the judgments of FNB and AgriSA, there is much to be concerned about.

And to top it off, the ANC’s legal fraternity feels confident that the courts will accept the contrivance of “nil compensation” to skirt very basic constitutional requirements that seek fundamentally to protect against abuse. I am inclined to agree with them: the courts will be reluctant to strike the Expropriation Act down on substance.

The majoritarian impulse to confiscate the property of a minority might have been more constitutionally digestible had the minority been granted the right to exclude the majority from their property. In exchange for a programme of redistribution, in other words, the minority has a strong right of exclusion and eviction on the properties they retain.

Alas, again, no.

Swiss cheese

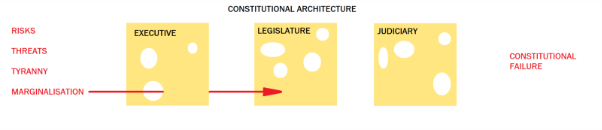

The Swiss cheese model, a concept borrowed from risk management and popularised by James Reason, illustrates how failures in complex systems like South Africa’s constitutional democracy occur when multiple layers of defence align imperfectly. This allows threats to pass through.

Each layer, like slices of Swiss cheese, represents a safeguard (e.g., oaths, Parliament, the judiciary) designed to protect liberty and limit state overreach. This is how, in the context of constitutional architecture, the system of checks and balances is set up:

However, we know that Swiss cheese does not quite work like this: there are holes in the cheese. And there are, necessarily, always holes in constitutional institutions; which is why you stack checks and balances atop one another.

A constitutional dispensation that works as intended, in other words, would look something like this:

In other words, at some point a “check” will “catch” the risk or threat that was missed by prior checks. This is why courts have appeals processes, why Parliament has two houses, and why the presidential term of office is definite and not unlimited.

However, failures of constitutional design are possible. Each “layer” of the Swiss cheese has holes – flaws or weaknesses – which could, under certain circumstances, align. This is why you should not place the Constitution on a moral pedestal as though it is perfection institutionalised. Failure, in this sense, would look like this:

When aligned across multiple layers, these holes in the layers permit catastrophic breaches, such as racialised expropriation or unchecked incitement to racial violence.

The model reveals why the Constitution’s fail safes have failed to a large degree: every layer, from the drafters of legislation to the courts, has holes of political bias, incompetence, and disregard for constitutionalism, and many of these have aligned.

Nothing good is waiting for anyone at the end of constitutional failure.

Running towards the Constitution

Indeed, if it is constitutional doctrine that violence may be incited against someone based on the colour of their skin, or that their property may be legally confiscated on the same basis, those on the receiving end of this abuse are entitled to ask whether they are bound, in conscience, to accept the very constitutional order per se.

This is especially the case if they are not allowed to respond in kind.

To be clear: nobody should want to live in a society where anyone chants about racial killing, or where property is under threat due to racial considerations.

But life is messy, and if you want the constitutional order to be legitimate for everyone who has to live under it, you do not have a choice but to choose: either nobody gets to chant “Kill the X”, or everyone gets to do it; and either nobody gets to racialise property relations, or everyone gets to do it.

The various checks and balances and failsafes in South Africa’s constitutional order meant to protect people’s liberties and interests have, in my view, already collapsed in substance if not in form, or are at perilous risk of doing so soon.

A fellow liberal recently urged us to “run towards the Constitution, not away from it.”

I share the sentiment.

Constitutions are crucially important tools for liberty, and you better believe that we are much better off in South Africa with the Constitution than without it.

But if our framework does not allow us to acknowledge when the tool breaks, and every check and balance fails, then our framework is flawed and needs revising.

Some level of allowance should be – must be – built in for legal subjects, individuals (the very core and main actor in liberal constitutional thinking!) to conclude that they are no longer bound, in conscience, to a legal order. An order that has not only failed to protect them, but refuses to recognise the basic equality before the law that is necessary to legitimise majoritarian democracy, and is in fact weaponised against their entirely legitimate interests.

Our framework must – and happily, liberalism does – recognise that there is therefore a need for robust, independent safeguards inside and outside of the state that check not only for state failure, but constitutional failure. These include an independent press and active civil society, yes, but also – quite uncomfortably for some – includes the right to be armed and to own property, and the traditional liberal (Lockean) right of rebellion held in reserve.

Running towards the Constitution is important while that option remains on the table – and in many respects, it does. But it would be irresponsible for us – a betrayal of our children – to convince ourselves that the option is there when, in fact, it is not.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend

Image: www.parliament.gov.za