With local government elections on 1 November, the respective political parties are stepping up their campaigning – and, with that, their numerous promises to a frustrated electorate.

A 44% unemployment rate and a 74% youth unemployment rate provide fertile grounds for statist and populist ideas and policies. But far from alleviating the country’s economic and societal woes, more government control and redistributionism will only add kindling to the fire.

A recent article in The Economisthighlights new research by academics Aroop Chatterjee, Léo Czajka and Amory Gethin. They find that in South Africa ‘the average income of the top 1% increased by 50%, while that of the poorest half fell by more than 30% after inflation,’ over the period 1993 to 2019.

Inequality qua inequality is not a problem, despite the many protestations from both left and right. In a free market, inequality results from voluntary choices between transacting individuals and businesses. People make their daily decisions, and try to use their skills and abilities to improve their lives, and their individual wealth can change rapidly. In a free market, those who respond best to consumer needs and wants by creating value are rewarded accordingly – they deserve praise for their endeavours.

However, inequality that results from force, coercion, or political interference and control is indeed a problem that can only be adequately addressed by separating completely the state from the economy. The less economic freedom a country has, the more politically fixed inequality becomes entrenched, and the only hope for anyone to really ‘get ahead’ is to have the correct politicians and bureaucrats in their back pockets.

Protectionism

Lower economic freedom also sees bigger corporates and those with the necessary connections advocating for legislation, regulations, and other forms of protectionism that ensure they are not subject to the robust competition that a true free market engenders.

In this scenario, wealth does indeed become ‘fixed’ – and the ever-smaller cake is shared between those with the most political clout. This is contrary to the organic wealth creation and fluctuation that takes place in a free market. Those countries that pursue more state economic control encourage more conflict between interest groups and individuals as they constantly jockey for position.

On the point of protected interests and, in my view, fixed inequality, Chatterjee, Czajka, and Gethin point to some of the progress that has been made in narrowing the country’s racial income gap since 1994. One of their papers finds that the narrowing is ‘mostly attributable to the emergence of a new Black elite.’ The article expands on this:

‘Once in government the ANC introduced affirmative-action laws, which have helped increase the share of well-paid jobs held by blacks, especially in the public sector, where trade unions have won above-inflation pay rises. Another policy, called ‘black economic empowerment’ has steered business towards black-owned firms and enriched a small number of black investors.’

When the government controls the economy directly (or indirectly, through reams of anti-entrepreneurial red tape), the wealth of the country does become a cake of a fixed size, making economic activity a zero-sum game where resources are divided up, as politicians deem appropriate, between various competing interest groups.

Declining economic freedom

With declining economic freedom in South Africa (evident in the drop from 58th place in 2000 to 84th in the latest edition of the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom of the World annual report), can we really be surprised when social tension flares up into protests and violence?

Given the country’s colonial and Apartheid history, there’s a strong practical argument to be made for some form of grant or welfare system. Indeed, a grant that combines all those currently available may cut down on some bureaucracy and be more efficient in terms of spending. But the academics mentioned above point out that:

‘regressive consumption taxes such as VAT mean the poorest have high effective tax rates. The child-support grant is not enough to buy nutritious food. Unemployment benefits are paltry and patchy; hence the growing campaign by NGOs for a universal basic-income grant. The “income”, as defined by the researchers, that the poor receive from public services is not the same as a pay cheque. And given the poor quality of schools and hospitals, it may be valued less by South Africans than by the authors of the study.’

Corrosive, anti-poor effects

Economists such as Mike Schüssler have often pointed out the corrosive, anti-poor effects of inflation – money simply does not go as far as it used to. Through pursuing destructive policies and massive spending programmes, government undermines the currency and undoes any potential benefits from its various welfare initiatives.

It is probable that government will continue to pursue policies that further its control over the economy, with yet more forms of taxation and redistributionism. But expropriation without compensation, National Health Insurance, prescribed assets, localisation master plans, and so on, will not deliver radical growth.

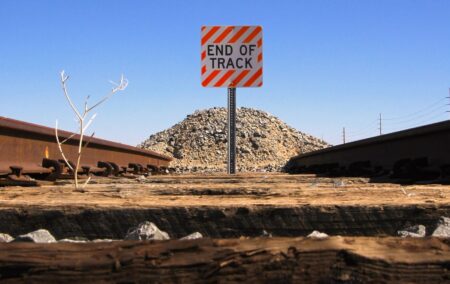

No matter your concerns with growing inequality – in the absence of a pro-economic freedom, and an enterprise- and investment-friendly environment, you simply cannot redistribute people into prosperity.

[Image: Joey Velasquez from Pixabay]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR, and are not necessarily shared by the members of the Free Market Foundation

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend