This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

28th January 1932 – Japanese forces attack Shanghai

Japan in the late 19th century had gone through one of the world’s most incredible transformations in world history.

In a period of just a few decades, it had moved from being an insular feudal kingdom of minor importance to being the first country of the 19th century to effectively modernize and restructure its society to allow it to compete in the modern world.

For centuries, China had dominated Asia as the supreme power and the centre of politics, with the most important question in East Asian politics being simply, ‘What is your relationship to China?’

Some countries like Korea and Dai Viet were subservient and took their place as tributary states of the Chinese emperor, being at least theoretical subjects of the Qing emperors in China. Others, such as Japan, resisted Chinese dominance and sponsored pirates and raids on China while also refusing to pay tribute to the ‘Son of Heaven.’

As a result of this general attitude to China from Japanese governments, despite the old and strong cultural ties between the two nations, Japanese rejection of the Chinese tributary system saw them largely excluded from trade with China.

After the Unification of Japan in the 1600s following a terrible civil war, the Japanese further isolated themselves from global trade, including trade from China, and would not interact seriously with foreign nations until the country was forced open in 1854 by American Admiral Matthew C Perry.

Japan’s subsequent rapid modernisation drastically upset the balance of power in Asia. The Qing dynasty in China had been humiliated by the British in the Opium Wars and yet failed to effectively reform. In contrast Japan by the end of the 19th century had a mostly modern army and navy backed with a growing industrial sector which could begin to match the power of the nations of Europe.

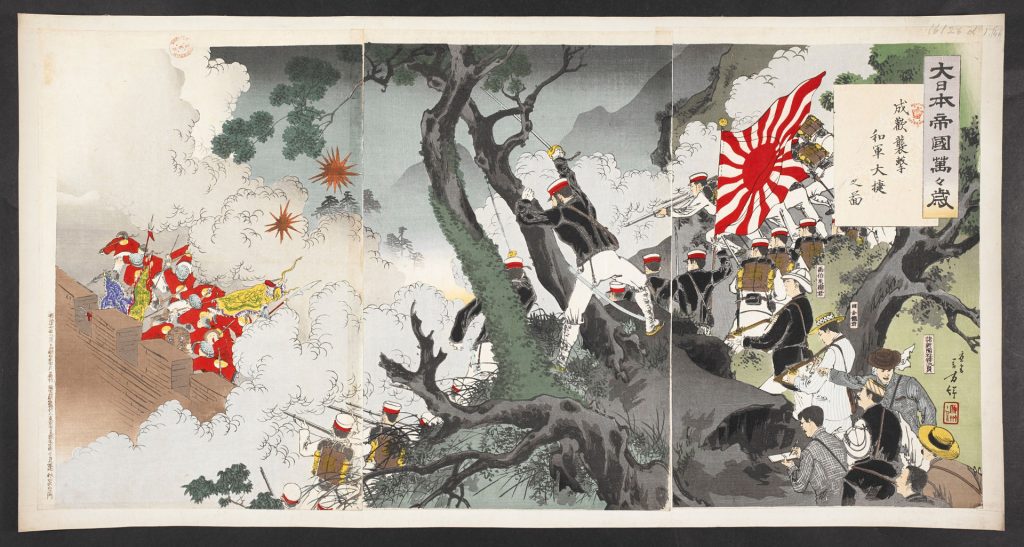

This wouldn’t be properly understood in China until in 1895 the First Sino-Japanese war would see Japan’s modern army crush the Chinese army, which was three times its size. This resulted in China ceding to Japan the island of Taiwan and control over the Korean peninsula.

Japanese propaganda during the First Sino-Japanese War: ‘Long live the Great Japanese Empire! Our army’s victorious attack on Seonghwan.’ (Note the ‘observers’ at bottom right)

While at its opening to the world in the mid-19th century Japan had, like China, to give away concessions to the European powers, such as ‘treaty ports’ (which while still technically belonging to the original country were effectively run by foreign powers such as Britain or France), at the turn of the 20th century the growth in Japanese power allowed them to renegotiate these treaties and abolish them.

In China, however, these ports remained and, in the final years of the Qing Empire at the turn of the 20th century, would be expanded.

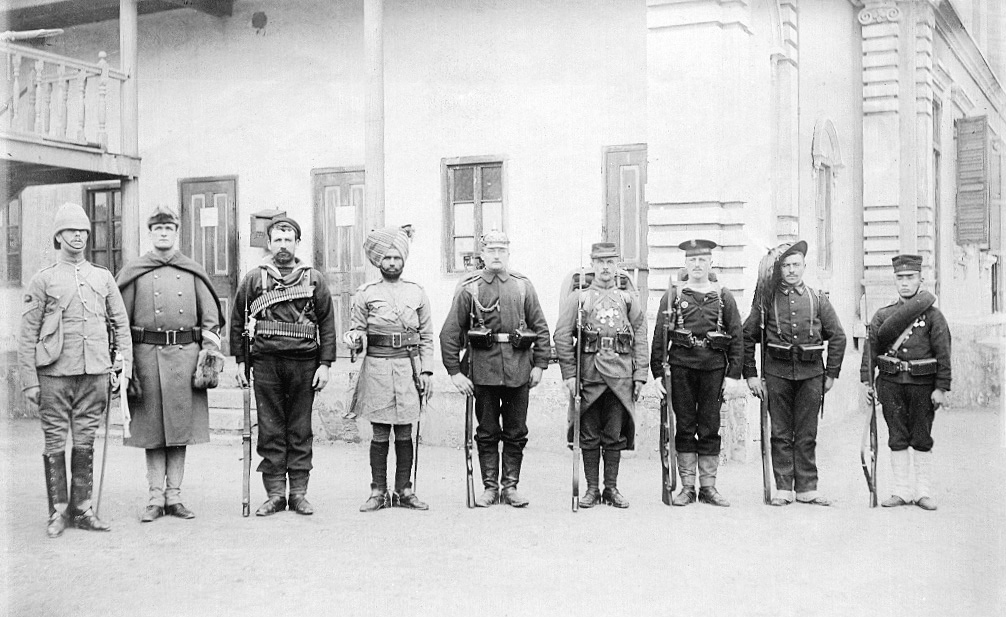

In the year 1900 after the outbreak of the ‘Boxer Rebellion’ – which targeted foreigners – an alliance of the world’s eight great powers was formed to crush the rebellion and protect expatriates. Their invasion was also an opportunity to carve out further concessions for themselves. This alliance consisted of the British Empire, Russia, Germany, the United States, France, Italy, Austria-Hungary and – securing its place as a great power – Japan.

The alliance crushed the Chinese and forced the Chinese to sign the ‘Boxer Protocols’, which was filled with various clauses that extracted reparations, weakened China, and allowed foreign powers to station troops in the various treaty ports.

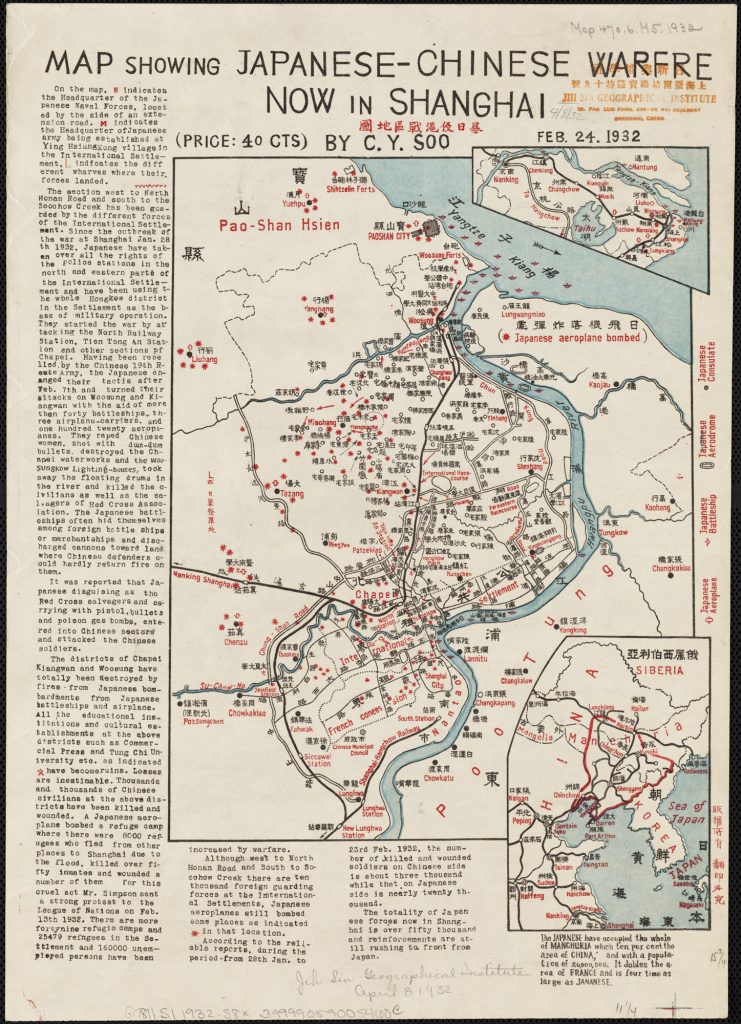

The most important of the treaty ports was that of Shanghai, which had an international settlement within the city formed from the merger of the treaty ports of the British and Americans in Shanghai and which, over the decades, grew to include representatives from many countries, including Norway, Spain, and Japan.

-774x1024-1.jpg)

After the ‘Boxer Protocols’ were signed, the Shanghai concession became home to troops from many of the nations represented there, notably Japan.

During the first decades of the 20th century China entered a period of yet more turmoil.

Chinese control over Manchuria was steadily lost to the Japanese and Russians, who fought a war over control of the region in 1904.

The Qing dynasty collapsed in 1912 and the country descended into chaos for decades until it was partially stabilised by Chiang Kai-shek.

Japan, frustrated by its lack of acceptance as a global power equal to those of Europe, gripped by the rise of fascism within its borders, and with its military hungry for the expansion of Japanese power across Asia, continued to undermine Chinese independence through the first few decades of the 20th century.

A group within the Japanese army called the ‘Kwantung Army’ – set up in the aftermath of the Japanese victory in the Russo-Japanese War – was responsible for the protection of Japanese interests in Manchuria, which while still in theory a part of China, was in practice largely controlled by Japan.

In 1931, the Kwantung Army decided that it wished to provoke a war with China, and so carried out a ‘false flag’ operation where they set off some fairly weak explosives next to a Japanese controlled railway in Manchuria (which failed to damage the railway), and then blamed the attack on the Chinese.

The Kwantung Army became a hot bed of radical fascist militarist officers who were desperate for war and for opportunities to win glory and power for Japan. The Kwantung was prestigious enough and powerful enough to be able to ignore orders from the Japanese high command without any punishment and often acted as a rogue army, doing what it wanted.

Some small skirmishes followed between Chinese and Japanese forces, but the Japanese government asked the Kwantung Army to keep the fighting localized and not to escalate things too much. However Kwantung commander Shigeru Honjō, decided to ignore this request and began a full-scale invasion of Manchuria.

The invasion quickly went in Japan’s favour and fearing a public backlash the Japanese government decided to support the invasion, and sent more troops to the area.

In 1932 the Japanese would establish a puppet state called ‘Manchukuo’ in the region of Manchuria, recognizing it as a new country in 1932, independent from China.

It placed the last Qing emperor, Puyi, (who was of Manchu origin) as their figurehead in control of Manchukuo.

As it became clear across China in early 1932 that Japan was about to humiliate China again and annex the north east of the country, anti-Japanese sentiment quickly spilled out into riots targeting Japanese citizens.

In Shanghai, these riots were encouraged by the Japanese, who let fascist Japanese monks into Shanghai to antagonize the Chinese and have them shout anti-Chinese slogans in public places, resulting in the monks being attacked and beaten. Japanese groups then responded, burning Chinese factories.

By 27 January 1932 things in Shanghai were tense.

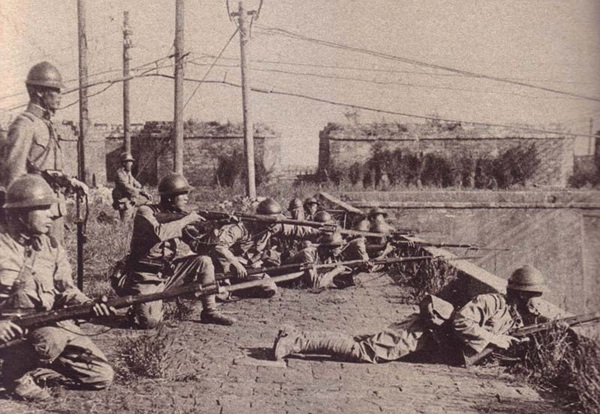

In preparation for an attack on the Chinese-controlled part of the city, the Japanese army had amassed troops in their section of the international settlement.

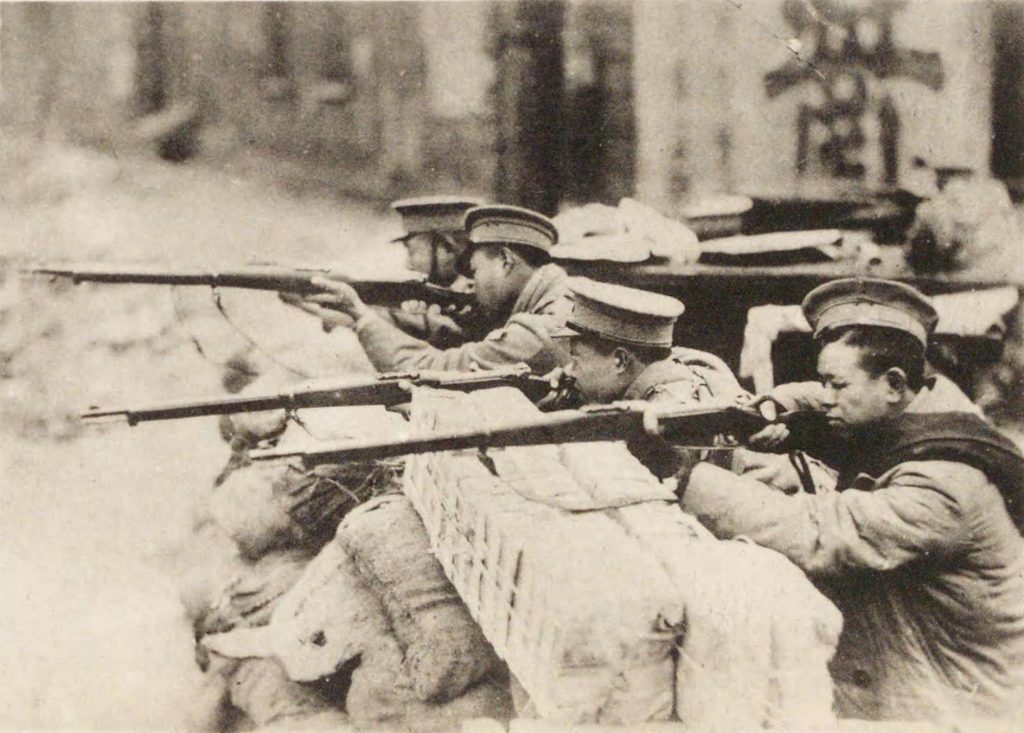

At the same time, a Chinese army called the 19th Route Army – essentially a personal army of Chinese general and warlord, Cai Tingkai – gathered outside Shanghai, seeking a battle with the Japanese.

The government of Shanghai feared both the warlord army outside the city and the Japanese army inside it and tried to keep peace between the two sides, even bribing the Chinese army to leave and not provoke the Japanese.

On 28 January, the Japanese issued a demand to the government of Shanghai, for money, and for action against anyone who was involved in anti-Japanese riots. The city quickly accepted these demands. However, that night the Japanese launched an attack, first with its aircraft bombing the city, and then with troops launching a ground attack. The 19th Route Army, instead of retreating, met the Japanese in battle, and the whole city would become engulfed in fighting.

America, Britain, and France, seeking to protect their own citizens living in the international settlement, would attempt to negotiate a ceasefire, but all attempts were rejected by the Japanese.

The battle over the city continued through February of 1932 and into March with more and more Chinese and Japanese troops arriving. In the end, the Chinese withdrew unilaterally on 6 March.

A truce was finally signed on 5 May, which saw the Chinese agree to demilitarize the area around Shanghai while allowing Japanese troops to remain in the city.

The domestic prestige of the Japanese army was increased by the victory in Shanghai and Manchuria. When, on 15 May 1932 the Japanese Prime Minister was assassinated by officers of the Japanese Navy, the effect was that the Japanese civilian government was cowed, giving the army and navy almost unchecked control over the state.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend