I’m no great admirer of Karl Marx. I say this having read a great deal of Marx’s own work, and a great deal by those of his intellectuals, Marxian and Marxist both. To my mind, his ideas have a dangerous eloquence that in practice have produced disaster after disaster. But for all that, I can’t help admiring his gift for expression.

One of his most memorable remarks, from The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, was this: ‘Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.’

The precise meaning of this remark is much debated, but the overall thrust seems to be that an epoch models itself on a previous one, producing comparable outcomes. The first is momentous and pathbreaking, its failures the stuff of high drama to be remembered forever. In its second iteration, it is predictable, petty and performative. It does not inspire awe, but scorn.

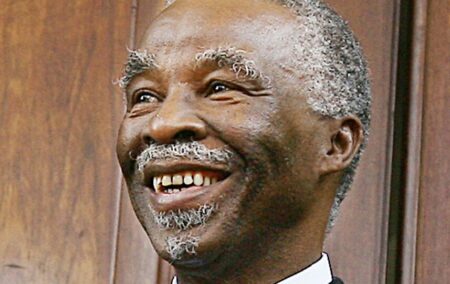

This idea comes to mind in light of former President Thabo Mbeki’s comments to the African National Congress faithful in the Free State.

The country, he said, was in deep crisis, plagued by unemployment, with state-owned enterprises failing, and the electricity supply unequal to the requirements of the economy or of the country as a whole.

‘The state is the biggest producer of electricity, and if we don’t produce electricity democratic SA dies,’ he said.

For good measure, he warned of the ‘agents of counter-revolution’ hiding within the ANC.

The solution to South Africa’s ills, he averred, was the ANC, which was in need of renewal, to be sure, but was indispensable to the country’s very viability. ‘If the ANC collapsed today, ceased to exist, this country would become ungovernable simply because of the influence of the party.’

Oddly familiar

If something seems oddly familiar about this, that’s because it is. And it would not have been entirely out of place during Mr Mbeki’s presidency. The scale and intensity of South Africa’s problems may be more extreme, but the problems themselves – unemployment, failing institutions, a deficient electricity supply – were all present when he occupied the Union Buildings.

That his presidency should have presided over this was a tragedy indeed. President Mbeki was intimately associated with the transition to democracy and the tortuous process of getting the country back on track afterwards. Don’t underestimate or devalue that accomplishment. Probably most importantly, he supported the prudent management of South Africa’s finances and macro-economic environment – earning him the resentment (if not the hatred) of the ANC alliance’s left. For a couple of years, South Africa topped 5% GDP growth.

Sadly, this coincided with corrosion from within, the ideological excesses resulting from a belief that the state could remake society if only it was imbued with an appropriate political consciousness. Hence the introduction of the ANC’s cadre deployment programme in the 1990s. An exercise in deliberate and counter-constitutional politicisation of what should have been professionally managed institutions, it is a key part of the explanation of what went wrong.

Former newspaper editor Brian Pottinger wrote in his book The Mbeki Legacy (a work I frequently turn to…):

Hardly had the edifice been crafted than it began to crack, as it inevitably would. The reasons were simple. The ANC did not have the skills base to control its own party efficiently, let alone the nation. Secondly, the deployment of inexperienced party figures into public-service offices led to a diminution of the offices themselves…

But the most serious effects of deployment were to be found when the one party in the (de facto) one-party state fractured in the run-up to the 2007 leadership elections. As the bureaucracy turned to counting who was pro-Mbeki and who was pro-Zuma, the already weakened professionalism of the public service took another nosedive. As directors-general hedged their bets by avoiding action on divisive policy issues, the very function of the public service became imperilled.

The supreme irony was that the mechanism to drive the state turned out to be its undoing. Even as Mbeki preached the virtues of a developmental state, the very foundations of the state were undermined.

Shockwave

That was tragic. South Africa squandered the political capital of its transition. The expulsion of Mbeki from office was a shockwave throughout the country. It demonstrated uncomfortable realities about the political makeup of South Africa, and confronted the country with a future coalition and a leader manifestly unfit to lead it: more unfit than Mbeki whose presidency had showed an expanding list of failings. Mbeki’s last year in office, in 2008, was dogged by load-shedding, the scandal surrounding police commissioner Jackie Selebi, well-merited disillusionment with his Zimbabwe policy, and the bloody xenophobic riots in May.

Today seems like a gaudy, inflated pastiche of 2008. There is catastrophic economic retardation after a decade of lousy growth. Load-shedding is now just a fact of life, a tax on existence. No longer are the country’s concerns focused on a crooked police chief – it has a ruling clique that has literally commandeered the state. And just how seriously South Africa is taken globally is a matter for debate.

And in July last year the state lost control of parts of the country in a blaze of looting and vandalism.

This is farcical. Comic after its fashion. There is scant political capital to squander, but an almost determined drive to squander it anyway – a sort of obscene deficit spending. The afflictions that were taking hold under President Mbeki were not only allowed to fester, but encouraged to do so, even as the effects became more and more destructive. Any hopes of a ‘New Dawn’ turnaround and a genuine renewal should have been scuppered by President Ramaphosa’s appearance before the Zondo Commission and his stout defence of cadre deployment. Consider the melange of policy proposals that at once envision enormous inflows of investment, smart cities and a green revolution, along with expropriation without compensation, prescribed assets and National Health Insurance – driven, of course, by a state that has failed in its current responsibilities. The ANC as an organisation struggles to pay its own bills – even, suspiciously, to the revenue authorities.

‘Grotesque mediocrity’

Tragedy, then farce. It brings to mind another phrase from Marx, this one from the preface to the 1869 edition of The Eighteenth Brumaire. He would, he wrote, ‘demonstrate how the class struggle in France created circumstances and relationships that made it possible for a grotesque mediocrity to play a hero‘s part.’

The circumstances and relationships that have led South Africa to its condition of ‘grotesque mediocrity’ overseen by those whose conceptions of themselves as playing a ‘hero’s part’ are too lamentably obvious.

Equally farcical and every bit as lamentable is the idea that the ANC holds the key to the country’s future security. To be sure, large dominant parties can exercise an important stabilising influence on fractious societies, but in South Africa, a good deal of that fractiousness is directly related to the conduct of the ANC, a point made in the recent report on last year’s riots.

‘Our renewal should be based on respecting and upholding the constitution of the ANC,’ Mbeki declared. He would have done better to suggest respecting and upholding the Constitution of the country.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend