As Russian isolation sent oil prices sky-high and bit into natural gas supplies, politicians respond to voter demand for action on climate change, and South Africa begins work on its National Infrastructure Plan 2050, it’s time for nuclear power to ride to the rescue.

Nuclear power has been in the doldrums lately, especially after the unwarranted hysteria over the Fukushima meltdown – which, ironically, proved just how extraordinarily safe nuclear power really is.

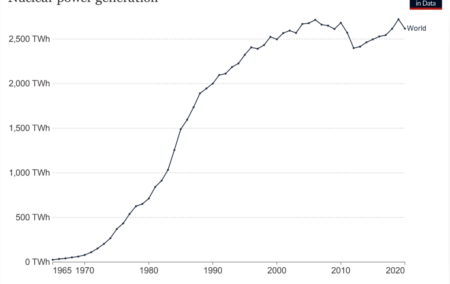

Total nuclear energy production has essentially flatlined since the advent of the 21st century, although 2019 did see a new all-time-high recorded, reflecting a modest recovery since the shock of Germany’s decision to shut down its nuclear fleet in the wake of Fukushima.

Despite this lacklustre performance, and despite the extraordinary growth in renewable energy production in recent times, nuclear still accounts for a significantly larger share of primary energy globally than solar and wind combined.

And all of these are dwarfed by oil, coal and gas, which remain, by a very long way, dominant.

The world wants to switch away from at least the more heavily polluting forms of fossil fuel.

According to the largest public opinion survey ever conducted on climate change, 64% of respondents believe climate change is a global emergency, and this belief is fairly consistent across all regions and income levels. In South Africa, 76% of respondents agreed.

Only 11% of those people don’t want to do anything about it; 59% want everything necessary to mitigate the crisis done urgently. In South Africa, 70% of those who believe climate change is an emergency want urgent action.

Popular opinion

Whether or not one agrees with these views is irrelevant. Even if popular opinion is wrong, what two thirds of the world wants, the politicians will scramble to deliver. That’s how they gain, and retain, power.

There is a wide variety of views on what, exactly, ought to be done about climate change, but switching from fossil fuels to renewable power is high on the list. The problem is, renewables simply are not cutting it, and they will likely never produce near 100%, or even a large majority, of our energy requirements.

Renewables still face major obstacles, including how to store energy for when the sun doesn’t shine or the wind doesn’t blow, how to sustainably source the raw materials needed and safely dispose of end-of-life toxic waste, high total life-cycle costs, high costs to connect widely dispersed small-scale generation plants to the grid, and more.

Where they have been deployed at large scale, such as in Germany and Denmark, household electricity has become the most expensive in Europe – about 50% more dear than in nearby France, which relies for more than two thirds of its electricity on nuclear power. Hungary and Bulgaria, the EU countries where electricity is cheapest, rely as heavily on nuclear power as they do on coal, and get only about a fifth of their electricity from renewables.

Added to the public pressure over climate change, there’s now a new geopolitical urge towards regional or national energy independence, to insulate countries from the vagaries of political instability and war. This raises the question: if not renewables, or not only renewables, then what?

Nuclear to the rescue

The answer lies in nuclear, of course. Not the old-fashioned mega-projects of yesteryear, but new-generation small modular reactors (SMRs) that can be built more quickly, installed in convenient locations, and provide reliable power for both baseload and peaking purposes.

The Economist newspaper is of the view that SMRs may be ready for prime time, under the circumstances. They are inherently safe. They can largely be built in factories and shipped to site rather than requiring complex construction projects on-site. Most designs rely on light-water reactor technology which is very well understood, including in South Africa. They could also supply heat for industrial processes.

Although the cost of construction remains an issue – and smaller is not necessarily cheaper – The Economist says nuclear power is looking less expensive than it once did. Moreover, they cite the International Energy Agency saying that ‘once the need for storage or backup generation is taken into account renewables are more expensive than their sticker price suggests’.

Recent independent, peer-reviewed research, in fact, suggests that nuclear power is more cost-efficient than renewable energy at reducing carbon dioxide emissions.

National Infrastructure Plan 2050

Patricia de Lille, minister of public works and infrastructure, earlier this month released a 77-page document outlining Phase I of the National Infrastructure Plan (NIP) 2050, and it is positively enthusiastic about the prospects of nuclear power in general, and SMRs in particular.

It says ‘[n]ew installed capacity will consist primarily of wind, solar and nuclear, where South Africa has a competitive and comparative advantage,’ and recommits the government to building 2 500MW of new nuclear capacity and extending Koeberg’s life well beyond 2024/5, when its current operating licence expires.

In particular, the paper argues that funding should be directed to ‘research and development for advanced and innovative nuclear energy system such as small modular reactors that are currently attracting global interest in terms of ease of deployment, modular approach to construction, alternate coolant used as opposed to water especially in the midst of climate change impacts on water scarce regions’.

In addition, it states: ‘The role of nuclear energy in achieving net-zero emission goals cannot be over-emphasised as it is evident in some countries of the G20 that already have Paris Agreement compatible plans and are aggressively deploying or considering ramping the share of nuclear in the energy mix… Seeing that no economy of the world can be powered wholly from renewables, there is room for co-existence of baseload energy source such as nuclear and renewables in so-called hybrid energy systems wherein the baseload energy source would kick in to fill the demand /supply curve when intermittent renewables are not available.’

It goes on: ‘The energy sector globally is experiencing the fastest rate of technological change and innovation ever in history, with significant growth in private participation at all stages of the value chain. However, it should be stated that the markets are indicative of lower costs of clean nuclear energy with the introduction of small modular reactors, this is a game changer in the future energy planning as the latter reactors could also be used in hybrid systems for hydrogen production, industrial process heat and in water desalination. There is clearly appetite in the South African private and public sectors to leverage these opportunities for a course correction.’

Likely referring to the EU’s reclassification of nuclear energy as green energy earlier this year, the NIP says ‘South Africa should embrace the global recognition of nuclear as a clean energy source’.

‘The inclusion of nuclear energy systems in the Green Taxonomy is essential to ensure that a low carbon future can be attained and net-zero is realistically achievable on a fair playing field.’

Finally, the document commits South Africa to sustaining nuclear research by replacing the Safari-1 research reactor at Pelindaba with a new multi-purpose reactor by 2030.

The NIP couldn’t gush more about nuclear if it tried.

Nuclear renaissance

There are critics who say that the ANC government cannot be trusted with nuclear builds, because of incompetence, corruption, or both. That is inarguably true.

However, it cannot be trusted with any other builds, of any nature, either, and that includes renewable energy projects. There is plenty of scope for corruption in any and all government infrastructure builds.

As for safety, modern SMRs are inherently safe, and won’t melt down even if something goes wrong. Vendors have a deep vested interest in overseeing safety standards in the deployment and operation of these reactors, since any significant incident could again put the global nuclear industry on ice for decades. With much of the manufacture occurring in factories under the control of vendors, rather than in the field, safety is further enhanced.

The geopolitical shock of war, sanctions and spiking fossil fuel prices might be just what the SMR industry has been waiting for. Imagine a fleet of small reactors, operated by competing private enterprises, supplying reliable, abundant and inexpensive energy to fuel South Africa’s re-industrialisation and long-term prosperity growth.

Now is the time to drive home the advantage, and bring about the nuclear renaissance that techno-optimists have been awaiting for decades.

The views of the writer are not necessarily those of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend.