Behind every stand the Institute of Race Relations (IRR) takes is a body of considered research, and a good alternative to bad policy.

I had to laugh out loud the other day when I came across a Facebook post that said the IRR ‘maak net ‘n lawaai soos ‘n klomp leë blikke’ (literally, only makes a racket, like a lot of empty tins).

I laughed mainly because there is something genuinely funny and essentially good-natured about idiomatic Afrikaans deftly handled, especially in the chiding cadences of a sharpish dismissal.

But if there’s no doubting that we do indeed make a lawaai, as we mean to, it’s more than merely kicking up a fuss – or being ‘alarmist’. Some detractors accused us of this last year when they thought the risk of expropriation without compensation was just so much election-inspired hot air that would dissipate into the ether before you could say ‘Max du Preez’.

There are three associated aspects of the work the IRR does that are often overlooked – particularly by those who are essentially irritated when they discover that we are unignorable.

First, we spend a lot of energy studying the data, the trends, the pronouncements, the bills as they emerge, and the laws they become, and we do so systematically over time.

On the strength of this, we do two things: we speak out vigorously, forearmed as we are with the data and insights that map the path the country is on; and, importantly, we offer alternatives.

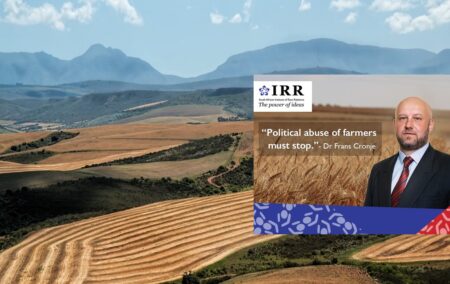

A good example of the first element of this process is contained in the speech given by IRR CEO Frans Cronje at last week’s meeting of Free State Agriculture in Bloemfontein. He made the point that the threat of property expropriation and the erosion of property rights is the product not of a sudden rush of blood to the head of the African National Congress (ANC), but of long-held ideological convictions exercised ‘slowly and deliberately’.

How did he know? Because, as he pointed out, the IRR had, over the past 12 years, ‘tracked more than 30 policy, regulatory, and legislative attempts to undermine property rights’.

He isolated a dozen of them. The first was ‘the 2007 attack on the willing-buyer/willing-seller policy at the African National Congress (ANC) conference in Polokwane’.

He went on: ‘Those attacks in turn informed the contents of the draft Expropriation Bill of 2008; this in turn informed the dropping of the Proactive Land Acquisition Strategy in 2010; then came the agriculture green paper of 2011, which forewarned of every risk from land ceilings to EWC – all of which would be drafted into policy and legislation within the next six years; a year later came the 20% proposal in the National Development Plan; the 50/50 proposal came hot on its heels; this was followed by the Land Restitution Amendment Act of 2014 that sought to provoke hundreds of thousands of new land claims without the budget to finance them; thereafter came the Property Valuation Act via which the State sought to lessen that budgetary bind; this was followed by the Agri Land Bill that sought to make the State custodian of all agricultural land, as the Green Paper had warned – thereby escaping any budgetary bind at all; then came the Regulation of Land Holdings Bill that would cap farm sizes and force farmers to surrender the surplus; this was followed by the proposed amendment to the Constitution; and, now, finally, there are the recommendations of the presidential advisory panel.’

The lawaai, then, is not a fuss for nothing.

As Cronje warned, against its long and steady gestation, the erosion of property rights ‘is the greatest threat not just to agriculture and to the broader economy, but to the entire constitutional edifice, to civil rights, and the rule of law that this country has faced in 25 years. If we do not defeat the threat, we doom South Africa to a future of poverty, and failure, and chaos’.

And the IRR knows there is another way, because it has worked it out.

‘We estimate,’ Cronje wrote last year, ‘that good-quality grazing land can be bought for R10 000/ha. To purchase a 1 000ha farm for a young, upcoming farmer would cost R10 million. We further estimate that to stock that farm with 200 in-calf cows would cost about R4 million.

A further R2,5 million would then be needed to provide the farmer with a new bakkie, tractor, trailer and implements. He or she could then be given R3,5 million in cash as working capital.

The whole investment would come to R20 million, and would create a debt-free commercial farmer, generating a positive cash flow of about R1 million a year and with more than sufficient collateral to buy more land and expand his/her farming enterprise.

The IRR estimated that a 10% cut in government’s wage bill would finance the establishment of an estimated 3 000 new black commercial farmers every year.

Under our model, they would be very well positioned to grow their businesses through their own collateral and cash flow.

And, Cronje wrote, the ‘rise, eminence, success and expansion’ of these new farmers ‘would be the most powerful answer South Africa could offer to the historical denial of property rights to black people’.

The IRR model was ‘simple, straightforward and cost-effective, and could be put into action within weeks’. But it would only work, he pointed out, if property rights were respected, and the agriculture sector was run as a market economy.

That’s what the lawaai is about – and why it’s critically important today.

Morris is head of media at the Institute of Race Relations.

If you like what you have just read, become a Friend of the IRR if you aren’t already one by SMSing your name to 32823 or clicking here. Each SMS costs R1.’ Terms & Conditions Apply.